For the descendents of Richard Dearie and his son John Russell

Left: Boh Plantations tea-estate nursery, July 1936

(New Straits Times Press, reproduced in Malaysia, A Pictorial History by Wendy Khadijah Moore. Archipelago Press. 2004)

Photo by Loke Seng Hon) (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons

Boh Tea. "In 1927 after thoroughly studying the matter of tea, which he (Archie) considered might be grown as a secondary industry in Malaya which so far was dependent upon Tin and Rubber only, and coming to the conclusion from statistics that high level tea seemed to weather periodic slumps he got in touch with A.B. Milne an old Ceylon tea planter, and together they applied for and obtained a large area in the Cameron Highlands which was at the time being opened up. After a year of so he bought out Milne and became the sole owner of Boh Estate which now has a planted area of some 1500 acres." Don Russell, writing in 1954.

(15/12/1928-VOL XVII NO.23) THE MALAYAN TIN AND RUBBER JOURNAL 1,415 Planting Section. MALAYA AND TEA CULTIVATION. Its Possibilities Carefully Examined. CLIMATE, SOIL AND ELEVATION FAVOURABLE. Capitalisation and Costs Examined. AN EXPERT’S INTERESTING VIEWS

Mr. A. B. Milne, the well-known planter, sends us the following special article on “The Possibilities of Tea Cultivation in the Malay Peninsula.” Mr. Milne is a pioneer planter of over 20 years’ experience of Malayan conditions and has considerable experience of tea planting in Ceylon and India, so that his considered views as to the possibilities of establishing tea cultivation as a permanent new industry in Malaya will be read with the keenest interest. Mr. Milne says: - Had it not been for the great boom and the general obsession in regard to rubber that resulted from it, it is probable that Malaya would by now have been producing an appreciable proportion of the world’s tropical hill products, tea, coffee, cocao, cinchona and the like—for every condition of soil, climate, labour and accessibility is suitable for such cultivation. The interest aroused by the explorations of the late William Cameron as far back as 1885 resulted in the commencement of a Government road from Tapah, designed to open up the country to private enterprise and to penetrate eventually into Pahang. The fact that at that time the village of Tapah was connected with the outside world only by river—there was no road north or south and the railway had not even been though of—reveals the trend of the pioneer mind as regards cultivation; sugar, coconuts and rice on the alluvial flats, with coffee, tea and so forth, as in Ceylon and South India, on the real hills. As for the foothills and the undulating, low-elevation country between them and the coast, it was hoped there might be tin found. In 1906, after many vicissitudes, the whole project was abandoned. Rubber had come upon the scene and the extraordinary ease with which it becomes productive and the extraordinary facility with which fortunes were made in it combined to blind investors to the claims of any other product whatever. Forgotten for Twenty Years. The fact that Malaya possessed a hill country at all was forgotten and remained forgotten for twenty years. Rubber would not grow up there so it was of no interest to anybody. A spirit evolved that planted rubber up to the very doors of cooly-lines and bungalows; that precluded the establishment of orchards or gardens; that classed as “eminently suitable for Hevea Brasiliensis” (a stock phrase of those days) any sort of land that possessed road or rail frontage. The result is that the economic stability of the country is dependent from an agricultural point of view almost entirely on the ups and downs of the rubber market. The cultivated area of Malaya amounts to 11.2% of the total area and of this, 58.3% is rubber, 32.4% is rice, 7.9% is coconuts and 1.4% represents other products. Which figures go to show what an opulent and wonderful country it is—and how indefensible is its economic position. It is obvious that Malaya stands greatly in need of agricultural development along new lines and it is equally obvious that Government should do everything possible towards the encouragement of such development. These notes are an attempt to recount the potentialities possessed by the country in the form of its neglected hill lands, more particularly in regard to the cultivation of tea. Space does not permit of entering here into the history and botany of the tea plant. Its use in the east dates back into prehistoric ages and it was introduced into Europe in the sixteenth century. It is of the Camillea family and there are two main species, the Chinese Bohea which need not concern us and the Indo-Burmese Viridis. Between these are innumerable hybrid strains which present many varying features so that the selection of stock exactly suitable to local conditions is a matter of primary importance. The World’s Tea Demand. The world’s production in 1926 was 871,000,000 lbs. of which India contributed 44%; Ceylon, 25%; the Dutch east Indies, 15%; China and Japan, 14%; Indo-China, Africa and other countries, 2 %. The United Kingdom consumed 57%; the Empire Colonies, 11%; Europe, 14%; America. 13% and Asia 5%. The consumption per capita in the United Kingdom has increased in the last ten years from 6.62 lbs. to 8.91 lbs., that is to say, by over 100,000,000 lbs., and in every country in the world, with the single exception of Russia, a steady increase has been maintained, especially in those countries which have come into prominence as a result of the war. New Zealand is the greatest tea-drinking country, consuming 10.92 lbs. per head, while Australia ranks second with 9.21. Russia, which up to the time of the revolution was one of the world’s chief consumers, absorbing about 100,000,000 lbs. of plantation tea in addition to some 80,000,000 lbs. from China, dropped absolutely out of the market until some three years ago, but is now purchasing again in rapidly increasing quantities. With this single exception, demand has gone on steadily increasing, consistently following in the wake of what is known as Civilisation, year after year, throughout the world. Little Room for Gambling. Tea has never been a particularly speculative market and in comparison with rubber, coffee, jute and other commodities, there has been but little of the gambling element in its history. The following are the results of fifty-three Ceylon tea companies taken from the monthly share-list issued by the Colombo Brokers’ Association for March last: - Capitalisation per planted areas …£74 Average area under cultivation …651 acres. Average dividend declared last Three years …27.8% Over the same period the twenty-three premier companies of North India, South India and Ceylon declared dividends averaging 76.4%, but it is only right to state that these are all old established concerns with capitalisation unattainable in these days. Generally, speaking, a high-grown tea produces quality—the chief constituent of which is flavour—at the expense of quantity, and this is an order which changes in inverse ratio as the altitude decreases. The low country produces more crop to the acre at a lower cost per pound but it cannot attain to this intangible quality of flavour and has, therefore, to be content with considerably lower process. For high grown teas there always has been and always will be a ready and remunerative market. The areas in which they can be produced are restricted and their development is becoming more and more costly and difficult. There never need be any apprehension in regard to the over-production of high-grown teas. On the other hand, any abnormal demand for common teas is immediately met by the adoption of course plucking on the part of the low-country concerns and is immediately followed by the market becoming glutted with a type that nobody wants, which has to be gradually worked off by means of blending with teas of finer quality, a business that takes time. To put it bluntly, there is quite enough low-grown, cheap-grade common tea in existence already. A start with 10,000 Acres. For purely local consumption, however, 10,000 acres or thereby might be profitably developed of low country tea, for Malaya imports some 11,000,000 lbs. annually—mostly absolute rubbish, but retailing at from $0.50 to $0.85 nevertheless—and consumption is increasing fairly rapidly. But the Dutch East Indies, China and Japan run this class of trade very close indeed and to attempt to compete in export might very well prove disastrous. Taking everything into consideration, I have no hesitation in recommending the prospective planter to concentrate on the hill land—the higher the better within certain limits—to pluck fine and to work for flavour. People who drink tea want good tea—there is no market more sensitive—and experience goes to prove that they do not mind paying for it. It was not until 1925 that public attention became attracted once more to the forgotten hill country of Malaya, when the foresight of Sir George Maxwell caused the road from Tapeh to be recommenced, and preliminary work to be started on the tract of country known as Cameron’s Highlands. This area, which lies on the Pahang side of the central range, consists of some four thousand acres of beautifully undulating country averaging just under 5000 feet above sea level and which is destined to become the real hill station of the Peninsula. Incidentally, it is highly improbable that Cameron was ever within miles of the place, but that is neither here nor there. The road, which is some forty miles in length and which should be completed in 1930, opens up further areas of excellent land at lower elevations as it penetrates into the mountains, but this need not concern the prospective planter, as there is nothing of any extent available either at the top or on the way up, Government having decided to allocate it purely as building sites, fruit and vegetable gardens and so forth, which is quite the soundest thing which could be done with it.

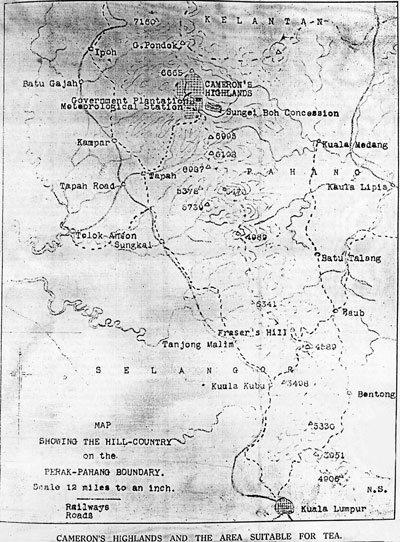

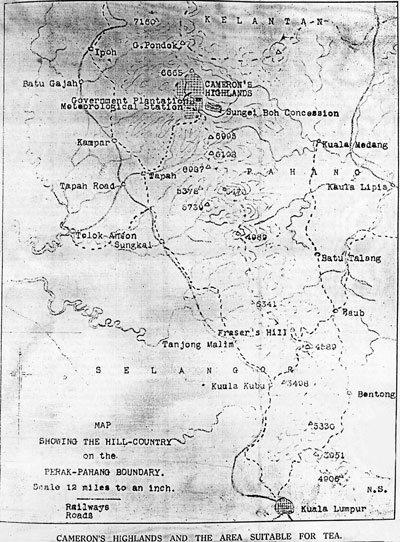

Road Into the Heart of Hill Country. What does concern the planter is the fact that the road opens out great possibilities towards the south and east and it would not be a very difficult of costly matter to run feeder roads up one or two of the valleys, sufficient to give access to thousands of acres of excellent country. At present this is the only road in Malaya that affords really practicable approach to high elevation areas. As the result of personal investigations extending throughout the length of the Perak-Pahang boundary from Gunong Pondok to Fraser’s Hill, I have no hesitation in stating that in this area alone there are anything from 75,000 to 100,000 acres available, land perfectly suitable in every respect for the cultivation of tea, Arabian coffee, cinchona and other hill products. It must be understood that this does not imply one great contiguous stretch like the rubber country further down. The most desirable land is that with an eastern aspect, of gentle contour, well watered and sheltered and not too remote from a main road of the future; the prospective planter may safely accept my assurance that areas of any size embodying all these desirabilities certainly take some finding. The general formation of the country is extremely broken and of the 400,000 acres roughly indicated on the map that accompanies this paper, I estimate that fully 75% is, for one reason or another, unsuitable. The eastern or Pahang slope contains undoubtedly the best land; its contours are more gentle and, taking it all round, its soils are rather better than on the Perak slope, although there are numerous small areas to be found there which are in all respects excellent. The main difficulty at present lies in the matter of access and it is to be hoped that Government, in planning the development programme of the near future, will not overlook the requirements of this magnificent stretch of country. The trunk road and railway that serve Perak on the west of the range run more or less parallel to the new road from Ruab to Kuala Medang on the east, the average distance between them being under thirty miles. There is nothing impossible in the idea of joining these up by means of connecting roads—bridle paths in the first instance—through two or three of the mountain passes and thus opening up the whole range to development. Of course everybody cannot expect to motor to his front door and it may be stated here parenthetically that much of the world’s finest tea is borne on pack mules or bullocks for very considerable distances. Six-foot jungle tracks, innocent of metalling, are serving vast areas in other countries while aerial ropeways are in steadily increasing use, cheap and efficient, throughout the mountain areas of the world.

Soil Entirely Suitable. The following statements have been made at various times regarding the soils of these hills most of the investigations having been carried out in the valley of the Bertam and in the neighbourhood of Gunong Batu Puteh, at altitudes of between 3,500 and 5,000 feet. (1) “Argillaceous, free, dark on the surface from admixture of decomposed vegetable matter and throughout of very superior quality I have seen cocao grow well in soil inferior to this. Unquestionably soil of great fertility…..Tea would certainly flourish in it.” (J. M. S. Cock, Superintendent of Government Plantations, 1892). (2) “The soil conformed in every respect to the requirements of good tea soils and there was no reason to be found why teas of good quality should not be produced.” (M. Barrowcliff, Agricultural Chemist, “Malayan Agricultural Journal,” Vol.X, 1922) (3) “In addition to bearing a striking resemblance to the best tea soils of India and Java, they have all the properties of good market garden soils.” (V. R. Greenstreet, Agricultural Chemist F. M. S. Bulletin, 1922) (4) “The soils generally are infinitely better than the up-country of Ceylon.” (F. G. Souter, Visiting Agent, Federal Council Paper No. 14, 1925) Other opinion, based on extensive practical experience, fully bears out the above. The average soils of the central range of Malaya are certainly among the best mountain soils I have ever seen and the whole country being covered with primeval forest, there has been little or no erosion and the humus of countless ages had therefore been preserved. This refers to the country between 3,000 and 5,000 feet, below which one is getting too low for tea in my opinion, and above which the nature of the land changes and begins to present features undesirable from an agricultural point of view.

Climatic Conditions. The following figures are extracted from the records of the Government Meteorological Station established at Cameron’s Highlands at an altitude of 5,120 feet. They may be accepted as typical of the extraordinary conditions obtaining in this particular portion of the Malayan mountain system.

AVERAGE RAINFALL OVER FOUR YEARS

|

Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sept |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

Total |

Aver |

1974 |

691 |

1041 |

1507 |

813 |

684 |

439 |

487 |

1102 |

1466 |

1490 |

1113 |

119.42 |

% |

10.7 |

4.3 |

8.7 |

12.7 |

6.9 |

5.8 |

3.6 |

4.1 |

9.2 |

12.3 |

12.2 |

9.5 |

100% |

WIND VELOCITIES

NUMBER OF DAYS

2MPH |

10 |

12 |

17 |

16 |

8 |

7 |

3 |

9 |

16 |

14 |

15 |

13 |

146 |

5 |

10 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

13 |

18 |

14 |

- |

11 |

7 |

12 |

144 |

10 |

5 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

7 |

8 |

14 |

- |

2 |

4 |

4 |

41 |

15 |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

2 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

- |

4 |

2 |

3 |

20 |

21 |

- |

2 |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

6 |

27 |

- |

2 |

2 |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

5 |

35 |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

2 |

Calm |

- |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

LONGEST PERIODS WITHOUT RAIN

Days. 3 4 1 2 3 4 9 2 1 - 5 4

The longest period actually without rain during the last four years is thirteen days.

The very best seed obtainable and the most thorough class of work have been provided for throughout these estimates—unless this particular job is well done, it is not worth doing at all—and most conservative figures have been adopted as regards production. I may say that I have seen so many promising ventures wrecked through undue optimism in regard to (a) rapid opening, (b) costs and (c) production, that I prefer to err, if error there be, well on the side of absolute safety. The Straits dollar is equivalent to 2s. 4d., so that these figures show a total capitalisation of just under £84 per acre brought to full production as against the generally accepted “self-supporting” stage, which would be roughly £75. On the basis of the market remaining at its present level of 1s. 6d., a property conducted on these lines would be self-supporting as from the fifth year, would repay its capital cost in full during the ninth year and would give returns at the rate of over 34% annually thereafter. These figures provide for a purely propriety undertaking; flotation expenses, agency and visiting fees, commission and other overheads have been omitted, but a decent living wage has been allowed for, with good permanent buildings and, as I have said, the very best class of husbandry. They are based on an area of 250 acres, opened up at the rate of 25 acres in the first year and 75 acres annually thereafter. It will be realised that the larger the area and the more rapid its development, the cheaper will be its ultimate cost. Planting Practice. Space does not permit of entering into the details of actual planting practice. A certain amount of technical knowledge is, of course, essential especially as regards manufacture, but in the initial stages this can usually be borrowed or bought. Generally speaking, no difficultly should arise that cannot be surmounted by hard work, common sense and attention to detail. To the prospective tea planter I would advise the exercise of caution, firstly, in the selection of his land; secondly, in the choosing of his stock and thirdly—and all the time—in the matter of opening up. There are little experimental patches of tea scattered throughout the Penisula and all that I have seen personally, whether on the hills or on the plains, have appeared healthy and vigorous, in spite of—in many cases—very bad treatment. There is no question as to whether tea will or will not do well in the particular region indicated in this paper; the experimental plantation established by Government on Cameron’s Highlands less than four years ago already affords ample proof of the suitability of both soil and climate. At the age of three-and-a-half years from seed, the tea is producing at the rate of 478 lbs. an acre, a type which appears to combine most of the qualities which are requisite in a good marketing tea, while as regards both growth and appearance, it is about the finest I have ever seen at any elevation or in any country. Government has at last awakened to its responsibilities in regard to the production of commercial asset other than rubber or tin and hill land has already been alienated for the development of tea, coffee and other products at a premium of $3 per acre and an annual quit-rent of $0.50 for six years and $2 thereafter. Under the present administration every facility is being afforded for the rapid development of the country by genuine investors, but, on the other hand, professional land-grabbers are very properly discouraged. Here in Malaya is unlimited land, fairly accessible, excellent in quality and cheap; an enlightened Government in one of the richest, most progressive and, incidentally, peaceful countries in the world; ample labour; perfect climate; a certain amount of sport; a sound and very remunerative investment and—a sahib’s job. Perak F. M. S, A. B. MILNE.

AN EX TEA-PLANTER’S VIEW Suitability of Cameron’s Highlands. (Specially written for the “Malayan Tin and Rubber Journal”) I should like to make some remarks regarding certain objections that have been raised against the cultivation of tea in Malaya in general, and on the Highlands in particular. It has been said that quality in tea is dependent on the prevalence of long droughts alternating with long spells of wet weather, but I have found nothing to substantiate this statement. It is true that in Ceylon, and elsewhere, teas with exceptionally fine flavour are obtained after the dry weather period, but I attribute this to a different cause, as I shall mention presently. Malaya’s Climatic Conditions. Our total rainfall for the year is about 120 inches against about 150 in other tea districts, and we have two distinct dry spells; moreover, our wet spells are nothing like so severe as they are in most other tea producing countries. As a rule the mornings are bright and sunny with rain only in the afternoon. If there is anything in this theory of alternate droughts and deluges, then we are at no disadvantage so far as the growing of tea in Malaya is concerned. Sunshine is the immediate cause of goodness in tea and we have plenty of this. Other tea-producing countries have found that the finest flavoured teas are gathered after the January-March drought, and have come to the conclusion that this is caused by the long dry period. I do not think this is attributable to the drought so much as to the fact that these good qualities are obtained during the Spring season, when all nature is responding to the swing of the sun to the Northern latitudes. If this really be the case, then the argument applies with equal force to Malaya. I would mention, as only one example of this, the annual wintering of our rubber followed by the beautiful display of new foliage, which coincides with the time the good quality teas are obtained. These extra good flavours are no doubt due to the juices that are produced by the plant in Spring, for the purpose of forming flowers and fruit. The urge towards reproduction is literally “nipped in the bud” by the tea-plucker, but it repeats the effort whenever favourable weather occurs and till the sun starts on its Southward journey. I am convinced that this is the cause of good flavour in tea and that we may expect the same effect in this country. Question of Soil. Apart from this, soil has a distinct effect on quality. In support of my statement I will quote from a book called “The Resources of the Empire” compiled and edited by W. A. Maclaren with a foreword by H. R. H. the Prince of Wales, and which contains authoritative information gathered from the most reliable sources:- “Moreover it happens that a garden adjoining one of the favoured ones, while making good tea, will not be able to obtain stand-out flavour, although the jat of the plant and the system of plucking and manufacture in the two gardens may be identical; in such cases it is evident that something is missing in the soil.” Now, if it is a question of soil, then indeed Malaya has a distinct advantage. I consider that ours is the best. These Hills possess excellent soil with great depth of humus and carry a heavy growth of timber, which is further proof of its good quality. The older tea districts have been in cultivation for many years past, and now resort to heavy and expensive manuring—in a great many cases land has been planted up on which coffee or some other form of cultivation has been carried on for considerable periods—our land, on the other hand, is covered with original forest and all that implies. Choose Highest Elevation. Yet another factor in quality is elevation. I have always advocated the planting of tea in this country at the highest elevations possible. Tea is a sub-tropical plant and must thrive best where climatic conditions resemble those of its natural habitat. In confirmation of this I must again quote from the book I mentioned previously: - “In the plains of India generally and in Ceylon, except at higher elevations, the quality of tea depends mainly on the care exercised in plucking and manufacturing the leaf; good drinking teas are produced, but without fine flavour. At the higher altitudes in Ceylon fine flavoured teas are produced.” It is here definitely indicated that fine flavour is mostly due to elevation. Mr. Kennaway has shown us that good tea can be grown in the low country of Malaya, and Mr. James French has also made tea on Carey Island and obtained good market valuations for it, but the almost irresistible conclusion to be drawn from these facts, is, that if good tea can be produced in the low country, the qualities produced in the Highlands should be even better. There is at present a little too much low grade tea produced in the world, and while I would not go so far as to say that the markets are overstocked any increase in the production of this quality should be avoided, for the present at any rate. Medium and fine grades meet with a ready demand which shows no signs of slackening off. In support of this assertion I will quote Mr. Eric Miller’s speech at the recent general meeting of Messrs. Harrisons, Crossfield Ltd., London. Best Teas in Strong Demand. “On the other hand, attractive good medium and fine to finest teas are in strong demand at remunerative prices, and those producers who exercise care in plucking and manufacture and market teas of attractive quality, are certain to obtain satisfactory prices for their crops.” Within the lifetime of the present generation, exports of Ceylon tea have risen from 19,600 lbs. to the enormous figure of 227,000,000 lbs. The increase in the world’s consumption has only been a little less remarkable than that of rubber and was estimated last year at 26 million pounds. Russia, before the War, was taking over 80 million pounds a year and is still out of the market. There is plenty of room for increased consumption and I see no reason why Malaya should not participate in meeting the demand. Malaya’s own imports of tea amount to about eleven million pounds annually and are retailed at very profitable rates. I have no doubt that all that could be produced in this country would be absorbed locally. Cost of Tea-Growing in Malaya. Finally, it has been said that the higher cost of labour in Malaya will operate adversely on cost of production as compared with those of other countries. I have gone carefully into figures and find there is no indication of this. Of this total expenditure on an estate only some 30 to 36 per cent. represents cost of labour and this fact robs the argument of most of its force. What has a real bearing on the subject though, is the larger crop per acre that our lands will most certainly produce and which should average the F. O. B. cost per pound of tea, down to a figure which will easily compete with those of other countries where labour appears to be cheaper. Furthermore, it should not be lost sight of that manuring in certain other tea districts costs no less than a penny a pound (Rutherford) and duty another ½ penny—items entirely to the good so far as Malaya is concerned. CHAS WILKINS.

Air Temperature. Mean Maximum …71.5 “ Minimum …55.7 “ Temperature …63.7 These figures are of peculiar significance and are worthy of careful study, for nowhere else in the tea-producing highlands of the world do such conditions prevail. The entire absence of high winds, of prolonged droughts and of periods of intensive rainfall, together with the soil conditions and the equable temperature, will undoubtedly combine to induce high productivity without those seasonal fluctuations in quantity and quality experienced elsewhere. The whole range is particularly well watered and ample cheap power is available from this source almost everywhere. With Cameron’s Highlands hill station at the north and Fraser’s Hill Sanitarium at the south, the health conditions of the intervening sixty miles of similar country may be taken for granted as being very good indeed. It is impossible to overestimate the vital importance of a healthy environment in the development of virgin country such as this, ensuring, as it does from the commencement, contented and efficient labour and executive, which ensures cheap and thorough work and good results. Malaya Popular With Labourers. The question of labour is of primary importance, for tea employs approximately five times as many coolies to the acre as does rubber. In all tea-producing countries in the world except South India, Java and China, the scarcity of labour and the difficulty of satisfying its steadily increasing demands form the chief problems of the planter. Agriculture all over the world is in the same boat; it is the penalty that has to be paid for what we call Progress. A careful survey of the position as affecting Northern India, Ceylon and Sumatra, discloses the fact that Malaya compares very favourably with those countries in point of recruiting facilities and cost, health and welfare charges, loss on foodstuffs and other overheads, while in the matter of the actual wages the higher rates customary in Malaya should be more than counterbalanced by the higher production consequent on virgin forest land as well as by the easy rates of tenure and the absence of taxation. Malaya has always been a popular country with labour of all classes which appreciates what may be termed the patriarchal policy customary in its treatment and there has never really been a real scarcity of labour in the history of the country. So far, the planter has depended chiefly on Southern India as the source of his supply and there has been little or no necessity for organised recruiting from other countries. Should such necessity ever arise, the good name that Malaya already possesses should ensure, from the teeming millions of Java and China, a sufficiency of first class labour at moderate rates. In common with all other plants, cultivated or otherwise, tea is liable to diseases and pests, but nothing has so far developed in its history that has not been more or less easily controlled. Under careful husbandry, disease need not be feared in tea more than in any other form of tropical agriculture. Estimated Cost of an Estate. The figures given below have been framed in relation to an actual block of average land which is situated some two miles from a main road and it is expected that the cost of the necessary connecting road will be shared by other concerns located beyond. Cost of factory and plant may also be reduced by co-operation with neighbouring properties, or the green leaf may eventually be disposed of to a central factory, thus eliminating this heavy item entirely—but it must not be forgotten that the other fellow’s factory has got to be paid for also!

ESTIMATED EXPENDITURE AND RETURNS ON 250 ACRES OF TEA LAND IN MALAYA CALCULATED OVER A PERIOD OF TEN YEARS FROM COMMENCEMENT OF OPERATIONS.

Expenditure

______________________________________________________________________

Capital Revenue |

Area Gross Annual Return on

Year Opened Annual Total Annual Income Profit Capital |

1st |

25 |

21,750 |

21,750 |

__ |

__ |

__ |

__ |

2nd |

75 |

34,225 |

55,975 |

__ |

__ |

__ |

__ |

3rd, |

75 |

35,387 |

91,362 |

__ |

__ |

__ |

__ |

4th |

75 |

45,163 |

136,515 |

__ |

__ |

__ |

__ |

5th |

__ |

17,395 |

153,910 |

17,275 |

19,200 |

1,925 |

1.08% |

6th |

__ |

14,340 |

168,950 |

32,865 |

43,200 |

10,335 |

5.83% |

7th |

__ |

9,000 |

177,250 |

48,059 |

74,400 |

26,341 |

14.86% |

8th |

__ |

__ |

__ |

53,115 |

98,400 |

45,285 |

25.54% |

9th |

__ |

__ |

__ |

57,305 |

112,800 |

55,495 |

31.31% |

10th |

__ |

__ |

__ |

59,570 |

120,000 |

60,430 |

34.09% |

|

250 |

177,250 |

177,250 |

268,189 |

468,000 |

199,811 |

112.71% |

ALLOCATION OF ABOVE FIGURES

General Charges

1. Prospecting for land $ 500

2. Survey fees, premium and quit rent 1,925

3. Supervision 64,810

4. General Transport 18,000

5. Office Expenses 5,700

6. Medical and Sanitation 15,900

7. Tools and Implements 5,700

8. Temporary Buildings and Fittings 1,200

9. Outlet Road, Construction and Upkeep 3,360

10 Upkeep Buildings 4,350

11. Recruiting and Labour Overheads 18,625

12. Contingencies at 5% on above 6,945

_____

$147,015

CAPITAL EXPENDITURE

Share of General Charges 63,095

13. Seed and Nurseries 14,680

14. Opening-up Clearings 37,500

15. Upkeep Clearings 18,900

16. Permanent Buildings and Furniture 18,665

17. Factory and Machinery 26,500

______

$177,250

REVENUE EXPENDITURE

Share of General Charges 83,920

18. Upkeep of Producing Area 43,900

19. Plucking, Manufacture and Transport 138,369

_______

$266,189

PRODUCTION AND COSTS

Year |

5th |

6th |

7th |

8th |

9th |

10th |

Estimated Output |

30,000 |

675,000 |

116, 250 |

153,750 |

176,250 |

187,500 lbs. |

Estimated F.O.B. |

57.5 |

48.7 |

41.3 |

33.7 |

32.5 |

31.7 cents |

Malay Mail, Thursday February 28, 1929. TEA-MARKING Growth of the Industry. TRIUMPH OF BRITISH GROWER The dispute in the tea trade with reference to the proposed application to tea of the provisions of the Merchandise Marks Act of 1926 has drawn attention anew to the enormous growth of the trade during the last half-century or so, says the “Financial Times. “ In 1867 the consumption of tea in Great Britain was just below 111,000,000 lbs, of which about 104,500,000 came from China and the balance from India. Sixty years later—1927—the consumption had risen to 416,ooo,ooo lbs, to which total India and Ceylon contributed 342,000,000, and the Dutch East Indies 61,000,000 and China and other producers about 13,000,000. The triumph of the British grower has thus been almost complete. Nevertheless the British grower is on his guard against foreign competition. At least it would seem this spirit of caution underlies his proposal that the provision of the Merchandise Marks Act of 1926 may be put into operation as regards foreign teas. Obviously it is the Java and Sumatra product which the Empire growers have in mind, as China may be safely disregarded. It may also be conceded that Java and Sumatra teas are not actually menacing the position of the British teas in this marker. But, all the same, the imports are creeping up. In 1925 the quantity of tea imported into Great Britain from the Dutch East Indies was 41,000,000 lbs: in 1926 it was 52,000,000, and in 1927 it was, as is indicated above, 61,000,000. In the circumstances it is not surprising that the Indian and Ceylon growers should be keeping a watchful eye on their Dutch competitors. And, after all, they are not really asking for very much. They do not suggest that the preferential Customs duty should be increased as against foreign teas. Nor do they ask that the Safeguarding of Industries Act may be invoked in favour of Empire producers. Their request simply is that every bag, packet, container or wrapper in which tea is sold in Great Britain shall bear what is known as an indication of origin. If the tea is British-grown, then the indication would be “Empire Product”, or other words to a like effect. If it is partly British and partly foreign it would be marked “Empire and Foreign,” and tea exclusively foreign would be marked “Foreign”. At first sight it seems, therefore, that the tea growers proposal is one to which there would be slight, if any, opposition. But, in point of fact, strong opposition to it was manifested at the recent Board of Trade inquiry by the blending and distributing section of the trade. The views of this section are, of course, entitled to the greatest respect, for it is the blenders and distributors who are largely responsible for the tremendous development of consumption in Great Britain. Stated shortly, their opposition to the marking seems to be that it is, in their view, impracticable. They say that if they are compelled to label their blends “Empire and Foreign” whenever they include Java or Sumatra tea they will be selling the same tea under different marks. If the marking creates a preference for the British-grown teas without any foreign admixture the result will be that the price of such blends will tend to rise. At least that is how the distributers view the matter, and there would seem to be force in their argument. Their views are, as has been indicated, entitled to much respect. But for the general public the question at issue surely is whether, in respect of tea, as in respect of other goods, the consumer ought not to be placed in possession of such information as will enable him to decide for himself whether he will buy Empire-grown tea or foreign-grown, or any blend of the two. And regarding the matter from this point of view, the case for the application of the provisions of the Act to tea would seem to be a strong one.

Malay Mail, Monday February 29, 1932. POSSIBILITIES FOR TEA GROWING IN MALAYA Rotarians Taste Locally Grown Leaves ONE WAY IN WHICH THE COUNTRY MAY BECOME SELF- SUPPORTING A survey of the growth of tea as a beverage and as an industry, followed by a discussion as to the possibilities Malaya holds for the capitalist and the smallholder interested in providing for local needs formed the subject of an address to the Kuala Lumpur Rotary Club at its weekly tiffin at the F. M. S. R. Hotel on Friday. The speaker, Mr. M. J. Kennaway, of Tanjong Malim, gave details of tea-plantations now existing in Malaya, both in the highlands and the lowlands. Instead of the usual coffee following tiffin, members took tea grown and prepared at the Sultan Idris Training College, Tanjong Malim, brought by Mr. Kennaway. The Hon’ble Mr. Arnold Savage Bailey, who presided, said it had been proved that highlands tea of fair quality could be grown in Malaya, and as the result of work at the Boh plantations, they would probably be in a position shortly to say that highlands tea of good quality could be grown commercially. He hoped that their attention would be turned to the growth and manufacture of tea rather than some of the older products from which the country was now suffering. As all the world knows both the name and beverage of tea came originally from China where it had existed from very early times and was in use as a drink in the 8th century although not introduced into England until early in the seventeenth century, but in the year after the Restoration it was still a curiosity to Pepys, said Mr. Kennaway. In the days of Queen Anne China tea began to be a frequent though still occasional indulgence of fashionable society but as the century wore on tea drinking spread rapidly and with Dr. Johnson it was no longer a curiosity or a fad but already a habit, indeed almost a vice, in which he indulged not sometimes but at all times especially after midnight. In 1703 the imports into the United Kingdom had been some 100,000 lb. but by the year of Trafalgar it had reached 7 ½ million pounds. Hitherto and for some time yet tea though widely used remained solely a product of China. In 1836 a sample of one pound had been sent to London by the East India Company after experiments in Assam. Two years later came a consignment of 488 lb. which fetched 9/5d a pound and in 1839 the first Indian Tea Company was formed. Today India and Ceylon have, 1,234,000 acres under tea with a yearly production of over 700 million lb. and incidentally supply over four-fifths of the United Kingdom imports. WORLD’S PRODUCTION. To sum up the figures for tea exports from the principal producing countries over the period 1924-29, one obtains the following results: In 1924, 763 million tons were exported, and in 1929, 866 millions. While the above figure includes a 15% increase for India and Ceylon tea and for the Dutch East Indies a 31 per cent. increase, for China it represents a decrease of 20 per cent. TEA IN MALAYA. Having now given you a few facts and figures relating to the history of tea outside Malaya, you may be interested to know what progress on a commercial scale is being made in this country. But before doing so I would like first to refer to a very common fallacy which widely exists, viz., that what is known as China tea is a different plant from that grown in India or Ceylon. Actually it is a plant with many similar characteristics, but differs in being much hardier, giving a richer flavour but with a smaller leaf and a much lower yield per acre. There are in fact many hundreds of acres of tea in and around Darjeeling planted only with seed from China but leaf from which is made into Indian tea. I have also made Ceylon tea from the China jat. There are however factors which no doubt account for the fine and delicate flavour of tea produced in China as compared with the thicker and more pungent flavour of Indian and Ceylon teas, viz, the different method of manufacture, which for centuries was a closely guarded secret of China, and also climatic difference. In China today, I believe, though I am open to correction, no tea factory on any large scale exists, and all tea exported is made by hand and I might add by foot, whereas Indian tea after being plucked is made entirely by machinery. There is also a different method in the fermenting process which is not adopted in India or Ceylon, but does, I understand, considerably assist in producing a different flavour. FUTURE PROSPECTS Now as regards the future prospects for growers of tea in this country. Since 1928 we have seen a world wide slump in all commodities including tea, yet if you will compare local retail prices today of imported tea with those in 1928 you will not find much more than a 10 per cent. reduction and best qualities are still fetching $1.00 to $1.20 per lb. Taking the cheaper grades of India or Ceylon tea or that consumed by the poorer classes, to which in these days we nearly all belong, the cheapest imported tea I can find listed is 80 cents per pound. In view, however, of the fact that 40 per cent. of our population is |Chinese if we are to make a serious inroad upon that 8 ¾ million lbs of tea annually imported into this country it is, I contend, the wants of the Chinese labouring classes, which we should endeavour to study and cater for. At present owing to the fall in the price of silver lower grade China tea is better able to compete with that grown locally but none of us anticipate this state of affairs lasting indefinitely and in the meanwhile we know that the Chinese labouring class can be gradually educated to drink the local product even though the method of manufacture is nearer to the Indian rather than the Chinese system. CAMERON HIGHLANDS. Taking now the higher grade teas or those which will probably be the first to be exported from this country. On the Cameron Highlands with our soil and climatic conditions very similar to those of Ceylon we have good ground for believing that eventually high grade qualities will be produced there always provided that close attention is given to plucking and manufacture. For consistent and what I might call commercial results we must look to the Boh Valley Plantations Ltd., which I understand will come into bearing in the near future. To the financiers and general managers of this property, Messrs. J. A. Russell and Co., who already have 600 acres planted in tea, this country is under a debt of obligation as, without the enterprise there shown there would have been no up-country tea produced on a commercial scale for another four or five years. By a commercial scale I mean an acreage in bearing sufficient to manufacture tea daily. OTHER ENTERPRISES. As regards progress being made in other enterprises in tea now in existence in Malaya: In Kedah you will find Bigia estate situated just under the Kedah peak at an elevation I believe of 200’ with an area planted in tea of over 700 acres. This estate has now established a local name for its Bigia brand and is, I am advised, able to dispose of all its crop locally and with steadily increasing sales. It must be recognised that there will always be a difficulty at first in getting dealers to change over to another brand of tea in so far as they usually sell under their own chop and have built up a business in their own line, but I am told it is only a matter of initial persuasion to get them to do so. There is also the factor that low grade Java tea unsuitable for European sale is to some extent being dumped in Malaya but, if more local supplies were available it is reasonable to assume that Government would, if necessary, assist the industry by the placing of an import duty on tea. It is however the opinion of the owners of this estate that there should be ample sale in this country for as much tea as can be produced locally for a long time to come. PERAK In Lower Perak there is a small European tea estate where the manufacture of China tea is being made a close study of, but this estate is only just reaching the producing stage. In Southern Perak also can be seen tea on a small scale now being produced at the Sultan Idris Training College. Here you will find not only an acre of tea, 3 to 4 years old, but also a small hand plant erected for the manufacture of the leaf which once a week is plucked and manufactured under the supervision of the Malay Agricultural Instructor belonging to the College. The tea made is of course not of a very high standard but I am assured by the Principal, Mr. O. T. ?Dumek, that it is appreciated and much sought after by the students and college staff, and preferred to the grades of imported tea they usually purchase. SELANGOR In my opinion this enterprise is of particular interest to Malaya in that we have here a definite object lesson showing us how Asiatics might on a small scale be encouraged to grow and manufacture tea for local needs. It is also of interest in that it is another indication of Malays taking to tea whereas in days gone by coffee was their main if not their only beverage. In Selangor in addition to an increasing number of Chinese small holding areas in tea it is of interest to know that in the Kuala Langat District there will be a European owned estate of 400 acres coming into being in 1933 if not before. So the manufacture of tea on a commercial scale in this State will shortly be and established fact. There is also an interesting experiment on Carey Island which has approximately 100 acres planted in tea and is therefore of particular value in that it is a tea-cum-rubber proposition. Only 27 acres are at present mature but during part of last year 6,000 lb. of made tea were produced and sold as a trial on the Colombo market. Owing, however, to the slump which had just set in and to the fact that it was not manufactured with proper plant, it only just repaid its cost of production. The experiment however is of further interest to Malaya in that it indicated that tea grown almost at sea level might with proper plant, etc., have competed with low country tea in Ceylon. AT SERDANG Coming now to the Serdang Experiment Station run by the Agricultural Department I would strongly advise those of you interested in tea who have not yet visited Serdang to do so as here you can see not only tea cultivation, but also its manufacture by machinery. At Ginting Simpah there is also I believe a small estate belonging to Mr. Choo Kia Peng which when more fully developed should owing to its higher elevation be able to produce a good quality of tea finding a ready market in Kuala Lumpur. In this short survey I do not claim to have referred to all the areas established in tea in Malaya, but only to those of which I have personal knowledge, but they are I think sufficient to shew you that tea growing on a commercial scale in this country is now almost established. Before concluding this address I would add that in the already overproduced state of the world’s tea market to-day I may be asked “Is it wise to urge that further areas be planted in Malaya?” To which my answer would be that so long as every year dollars running into millions are going out of this country to pay for our imports of tea so long should every effort be made to make Malaya self-supporting in this respect. Incidentally it would materially help us in our unemployment problem.

Extract from: " Development of the Cameron Highlands up to the End of 1934". BOH PLANTATIONS. The original grant of approximately 5,000 acres was granted to the Company in the valley of the Sungei Boh in 1929 and by the end of 1929, 55 acres had been planted in tea and 350 acres had been felled for development. In 1930 and 1931 planting was pressed forward and at the end of 1931, 535 acres had been planted in tea, 193 acres in coffee and 620 acres felled for future development.

In 1932 a re-orientation of the boundaries of the Company's property took place as it had become evident that a large portion of the 5,000 acres originally approved lay at lower elevations than were considered suitable for the production of the best possible quality tea. A large area of the high elevation land between 5,000 feet and 6,000 feet above sea level and adjacent to the original boundaries was included at the expense of the low elevation land and the whole property of the estate reduced to 4,037 acres.

During the year plucking of an experimental nature, took place over the tea area planted during 1929 and the leaf so produced was sold to a Chinese contractor who, by somewhat primitive methods, converted it into a “semi-fermented” tea which found a ready sale amongst the Chinese community on the plains.

At the end of the year there were 610 acres planted in tea. The following is the total development progress at the end of the year:

610 acres planted in tea, 193 acres planted in coffee, 36 acres planted in cardamoms, 659 acres felled for future development, 2,539 acres of reserve virgin forest Total 4,037 acres.

During 1933 the access road was constructed.

The distance from the main Government road (main road Tapah-Tanah Rata at the 82nd mile) to the estate boundary is 2 ¾ miles and from this boundary a further 1 ¼ miles was constructed to connect with the developed portion of the estate.

A start was made on a factory site.

At the end of the year progress made was as follows:

610 acres planted in tea,

196 acres planted in coffee, 50 acres planted in cardamoms, 642 acres felled for future development, 2,539 acres in reserve virgin forest. Total ... 4,037 acres.

1934.—With the excavation of the factory site completed early in the year building operations commenced on the 1st of April and the first manufacture of commercial black tea by the process generally employed in Ceylon and India took place on the 28th July, just four months later and has continued regularly since. The first consignment of tea was sold in London during November realising not unsatisfactory prices considering that the leaf being plucked and manufactured is in the main part still very immature and that with the unskilled labour manufacturing conditions at the start left much to be desired. It is considered that a year or two will elapse before the larger portion of the present planted areas matures sufficiently to give the high quality tea which the Company expects to produce, and, has in fact indications, will' be produced.

MINUTES OF THE ELEVENTH MEETING OF CAMERON’S HIGHLANDS DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE HELD AT THE OFFICE OF THE DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC WORKS, KUALA LUMPUR, ON TUESDAY, 17TH JULY, 1928, AT 10 A.M. PRESENT The Hon’ble Director of Public Works, Federated Malay States (Chairman). The Conservator of Forests, Straits Settlements and Federated Malay States. The Acting Surveyor-General, Straits Settlements and Federated Malay States. The Acting Secretary for Agriculture, Straits Settlements and Federated Malay States. The Government Town Planner, Federated Malay States. DR. A. R. WELLINGTON. MR. E. N. T. CUMMINS. MR. D. H. HAMPSHIRE. ABSENT The State Engineer, Perak. IN ATTENDANCE Mr. B. O. Bush (Honorary Secretary). The Chairman stated that at this meeting he proposed to depart from the usual order of proceedings in that he would first of all read a memorandum from the Hon’ble the Chief Secretary, dated 14th July, 1928, before dealing with the minutes of the last meeting. The memorandum, dated 14th July, 1928, by the Hon’ble the Chief Secretary was then communicated to the Committee. A compilation of official ratings and minutes in connection with Cameron’s Highlands together with a digest of the interpretation by an unofficial of similar powers on the Fraser’s Hill Development Committee was laid on the table for each member. Mr. D. H. Hampshire stated that paragraphs 4 and 5 of the powers of the Fraser’s Hill Development Committee in the document referred to above seemed to him to be contradictory. The Chairman pointed out that what was meant by these paragraphs was that the Committee had powers to allocate the Block Vote but the Director of Public Works was responsible, in that capacity, for the spending. THE AGENDA WAS THEN TAKEN. 1. MINUTES OF LAST MEETING Section 1, para. 12.—Discussion took place as to whether the words “with the following addition” should be added after the words “the report was adopted”. It was agreed that the minutes as circulated would stand. Section 3, Felling and Clearing.—It was finally agreed after discussion that the words “and 20 acres” should be added after the words “Altogether about 100 acres were felled”. Section 5, Felling and Clearing on the Highlands.—The wording of the whole of this section was discussed at some length and finally it was decided to add after “Mr. Cummins” in the fourth sub-paragraph, the following words: “pointed out that the policy decided upon seemed to him perfectly clear and”. The minutes as amended above were then confirmed and signed by the Chairman. 2. MATTERS ARISING OUT OF THE MINUTES OF THE LAST MEETING. Item 2, section 8.—This report had since been received and circulated to the members. Item 3.—The report called for in the last paragraph of this item relating to the high cost of the work done by the Burma Rifles had been received by the Chairman who stated that the decision to send the Burma Rifles to Cameron’s Highlands had been made by the Committee. The Public Works Department Officer at the Highlands had not been consulted, his only instructions were to give every assistance to the detachment. The work was carried out under the supervision of the officer of the Burma Rifles. In the discussion which followed as to the responsibility for the expensive and bad work, the Chairman stated that he did not feel that he could justifiably hold the he Public Works Department Officer responsible for the work of the Military and that he therefore accepted it in virtue of his office as Director of Public Works in charge of the expenditure of the Development funds. Item 5.—Under the last paragraph of this item the Chairman informed the Committee that he had received telegraphic advice that up to the present undergrowth above Tanah Rata had been cleared over 130 acres and at Lubok Tamang 45 acres. These figures must, of course, be regarded as approximate. At Ringlet the work had not yet been started. 3. PROGRESS REPORT FOR THE MONTH ENDING 31ST MAY, 1928.—The Chairman stated this had been received and a copy would be sent to each member. He invited the attention of the members to an interesting paragraph in the Reconnaissance Officer’s Report related to a visit to a reported exceptionally fine topped ridge encountered in exploration across the Sungei Rotan. 4. APPLICATION BY LAND FOR MR. A. B. MILNE.—It was stated that application for 5,000 acres of land outside the Highlands Proper had been received by the Hon’ble British Resident, Pahang, from Mr. A. B. Milne. The application had been referred to the Committee for their opinion on: (a) The desirability of alienating so large an area to one individual; (b) The desirability of alienating this particular block. The discussion indicated that the members were of opinion that as the land applied for lay outside the Cameron Highland’s area, consideration of this application did not fall within the jurisdiction of the Committee, though if this land or any part of it were ever alienated access to such an area would have to be over the Highlands Roads via Lubok Tamang. It was finally agreed to reply to the Resident’s enquiry in the following terms: “The application of Mr. Milne was referred to the Committee for consideration. It was considered that the question of the alienation of this land did not at present fall within their province, but they wished to point out that it was not possible at present to state what facilities for access it will be possible to give through the Highlands.” 5. HEALTH REPORTS FOR MARCH AND APRIL.—These had been received and circulated and members were advised that the reports for May and June had since come to hand and would also be circulated. Dr. Wellington proceeded to speak of his observations during his recent visit. He stated that from previous reports he had formed the impression that the health might not be all that could be desired but during his visit he had found nothing to which exception could be taken. Beyond the 20th mile there was no evidence of malaria contracted on the hill. Between the 15th and 20th mile at Jor there was evidence of the danger of malaria infection—not much—but it was there and being attended to. Beyond Jor, of the 2,000 people there only a few were in hospital; in fact far less than one would expect of a similar labour force on the plains. He explained that there was a vast difference between relapses in malaria and re-infections and steps were being taken to distinguish between these two classes in the returns to avoid incorrect conclusions being drawn. Asked if he was quite satisfied with the present position Dr. Wellington stated that he was entirely satisfied and that he was glad to say that the fears expressed previously in some quarters had not materialised. This statement was received by the Committee with great satisfaction. 6. PRINTED MINUTES OF 8TH MEETING.—Attention was drawn to an unfortunate omission in the printed minutes, the words “including Lubok Tamang and Ringlet areas” had been omitted in section 7, sub-section v, which members had since been asked to rectify. 7. DELAY IN CIRCULATING THE MINUTES.—The Chairman stated that certain members had pressed for more prompt circulation of the draft minutes. He explained that frequently there were difficulties to overcome in this respect. The Reporter and he had many other matters to attend to, and in the case under criticism a meeting of both the Federal Council and Legislative Council had interposed before the notes could be transcribed. Efforts were always made to circulate the draft minutes as early as possible. 8. REPORT FROM THE AGRICULTURAL DEPARTMENT ON THE HIGHLANDS.—This has been received and would be circulated. It was a very full report dealing with the growing of grass, vegetables, etc. Being a document of considerable length with a plan attached, it would not be copied for each member but kept for reference after circulation. 9. ALLOCATION OF DEVELOPMENT VOTE.—It was stated that a further supplementary provision of £40,000 had been approved; this called for a re-allocation. A suggested allocation was discussed and it was finally decided to defer the matter until the next meeting, the $40,000 being added to the unallocated reserve for the time being. Under this heading the growing of vegetables was mentioned and it was decided not to replace Mr. Jones lately transferred. The vegetables now being grown could be looked after by the tindal under the general supervision of an Assistant Engineer. 10. ROADING.—A map and a communication from the Zoning Sub-Committee had been received and the Chairman advised the Board that these had been sent to the State Engineer, Perak, and read out his instructions which accompanied them. 11. ZONING SUB-COMMITTEE’S REPORT.—The Chairman stated he was of the opinion that the reports already received from the Zoning Sub-Committee should be considered as interim reports for the information of the Committee, but not as final. The final report, when submitted, could be gone into fully by the Committee and approved or disapproved. The Government Town Planner pressed that the reports be submitted to the Committee regularly, as he wished them to form a series of stages by which the final report could be built up, and he could not do this unless the Zoning Sub-Committee carried the General Committee with it, by reason or the approval or otherwise of the interim reports. A discussion ensued as a result of which it was decided that the Zoning Sub-Committee’s Reports should “be considered as interim reports for the information and advice of the General Committee and that no decision or action thereon should be settled unless the Zoning Sub-Committee had sent its full and considered report and recommendations for the preliminary zoning and lay-out of the Highlands generally. 12. REPORT OF A VISIT TO THE HIGHLANDS BY THE CONSERVATOR OF FORESTS, DR. WELLINGTON, MR. CUMMINS AND MR. HAMPSHIRE.—This report was discussed first in general terms and then item by item. It was agreed to leave the Rest House at Jor intact until it had been found to be no longer required and the provision of a Chinese Cook and Tukang Ayer at this rest House was agreed to. Certain improvements and repairs to the Rest Houses, etc., were also approved. The question of felling and clearing a belt four chains wide round the area proposed froe recreation was discussed at length. The Conservator of Forests stating that, though he was as opposed as ever to wholesale felling and clearing, he withdrew his opposition to this particular felling as he understood that the line would follow the first nine holes of the proposed Golf Course. It was pointed out by the Government Town Planner that the Golf Course was by no means fixed, the siting of the course would have to be made to fit in with other items of development such as roads etc., of which the Golf Course was only an element. After further discussion this felling was agreed to on the principal that the clearing would be of great value in observations with a view to development, that the first nine holes of the Golf Course would probably follow this line and that, if in future it was found necessary to do so, any part of the proposed Golf Course should be moved. The paragraphs of this report relating to the methods of clearing undergrowth and agricultural experiments were approved. The sum of $3,000 was allotted from the Block Vote for the Conservator of Forests to proceed with his scheme of sawing timber under paragraph 15 of the report. It was agreed after discussion of paragraphs 12, 19 and 22 to defer these matters until the next meeting. 13. REPORT OF MR WISE’S VISIT TO ULU JELAI IN 1896. —This report was mentioned as having been received and would be circulated to the members. Meeting adjourned at 1.30. p. m. From National Archives of Malaysia. Selangor Secretariat (877/1928). Transcribed by P.C