For the descendents of Richard Dearie and his son John Russell

The Batu Arang Plywood Factory 1939 -1942

Further extracts from “ No Medals" , the memoirs of Thiel Marstrand. To read the whole document click here.

PART II MALAYA AT WAR 1939-1942. In March 1939 after 6 months leave in Norway Thiel returned to Batu Arang. (Numbers in bold are page numbers from the original typed manuscript. Headings in bold have been added by C.G.)

The Batu Arang Plywood Factory 1935 -1942

Extracts from “ No Medals" , the memoirs of Thiel Marstrand, who went to Malaya in 1935 to work at the Plywood factory. To read the whole document click here.

Thiel Marstrand had worked in a plywood mill in Norway and went to Malaya in 1935 with his wife Molle and their three year old son Claus. He was there for 7 years.

(Numbers in bold are page numbers from the original typed manuscript. Headings in bold have been added by C.G.)

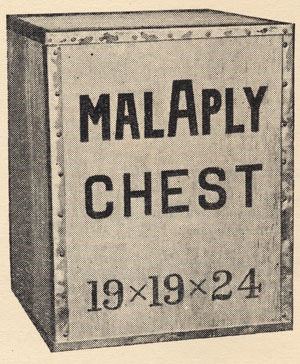

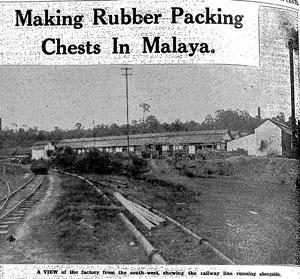

The Malayan Collieries Director's report for 1931 included the addition of plywood for building and packing purposes to the general products of the company. The general manager's report included:"Plywood.- This department was brought to production stage by the end of the year, and commercial sales of the products have since commenced. To date, the production of building–panels and chests for packing rubber has been concentrated upon with, we are pleased to say, quite encouraging results."

Extract from Archie's speech at the 17th A.G.M. of Malayan Collieries 31 March 1931: "During 1928, we purchased the land, buildings and plant of Malayan Veneers and Plywood Co., Ltd (in liquidation) adjoining our Batu Arang property. The purchase was made on the basis of a conservative valuation of the land and building for use as colliery coolie lines; although it is our intention to investigate the possibilities of the plywood plant for utilising the waste timber obtained by the company in the course of its production of pit props and other wood used on the colliery. During the year several of such waste logs were sent to the continent, and considerable research work was carried out upon alternative glues and cements. Owing to the nature of the reports obtained, towards the end of the twelve months it was decided to start up the works upon an experimental basis. The results of this experimental work are encouraging, and, subject to the condition in which some trial plywood cases arrive in England, we may decide during the current year to bring the factory to an initial small-scale commercial production. This can be done with a minimum of additional cost, and this department, favoured as it would be with an exceedingly low capital outlay and the utliisation of a waste product, should be the means of contributing a little to the general prosperity of the company."

The Malay Mail, Thursday April 2, 1931, page 3.

By April 1932 Archie could report at the A.G.M. that:"Since last addressing you, the plywood manufacturing department at Batu Arang has been brought into commercial production and I am able to say that the demand for the product is encouraging. We could quite safely say that the demand was entirely satisfactory but for the well known fact that prejudices die hard. While we are able to offer a pink or redwood chest possessing all the qualities of the best imported chests except for colour, plus considerable price advantage, the majority of buyers are reluctant to adopt them, and so the real demand to date is for our Class ”A” or whitewood chests, which, owing to the lesser abundance of suitable white timber, is rather more expensive, but still definitely competitive.

The capacity of the plant represents but a small proportion of the total chests imported into the country; but even so it is a step, both in principal and in practice, towards reducing the colossal sums spent annually on importing timber and timber products into this country, articles which could and should be produced locally.

The net importation of timber, in the form of lumber only, into British Malaya has averaged during the last three years no less a sum than $2,500,000 and actually in tonnage and value was greater than that officially produced within the country itself. In so well wooded a land as British Malaya, where Government has spent literally millions on forest administration and research, this is an astounding anomaly that reflects gravely on our F.M.S. system of economy. In the Philippines, with similar forest resources, lumber is one of the principal internal and export industries, and a source of great employment to the people and of revenue to the State.

Exploiting F.M.S. Forests. In British Malaya thousands of acres of precious timber have been in the past destroyed for planting and many more thousands will be so destroyed when the planting industry revives. This is no criticism of the planting industry; but of the system which after years of running an expensive administrative and research department has apparently not yet devised a method of profitably exploiting our several large areas of excellent forest before the same is alienated for cultivation; nor, it would seem, of being able to encourage others to exploit them."

The 1933 annual report stated:"An application was lodged with Government for a timber area within working distance by rail of Batu Arang and there is every hope that this will be granted. The timber requirements of the Company are steadily increasing, and as a secondary consideration it is proposed to respond to the insistent demand of Empire markets for timber of Empire origin, by supplying some of the Malayan timbers which have been favourably reported upon, but which have not hitherto been available in a suitably manufactured form, or with any assurance continuity of supply. A wood distillation plant, which was installed new some time ago in Pahang by a company now defunct, was acquired at only a fraction of its original cost, and it is hoped during the current year to prove that wood distillation, though not hitherto successful in Malaya as a separate entity, may be made a technological and financial success when developed and operated as a department of an existing undertaking for the utilisation of an at present waste product."

At the 19th AGM H.H. Robbins read out Archie's speech which included:

"As an extended source of supply of timber for our existing operations, and to enable us to further expand our operations, by milling suitable kinds of timber for export, we have applied to Government for an area of 28,000 acres of timber land within a working distance by rail of Batu Arang, and for the right to select a further similar area within a period of years. Government has not yet conveyed its official reply, but we understand that our application has been favourably received. The opportunity presented itself for the acquisition of a complete logging and sawmilling plant, together with some 10 miles of railway track and all necessary rolling stock for conveying logs from the forest to the Sawmill. Though the area of forest land required to justify this plant was not actually granted us, we felt justified in purchasing the plant upon the terms which we were able to negotiate, and it is now at Batu Arang awaiting the decision of Government. I should like to say that our proposed entrance into the timber milling business with plant of a larger capacity than that which we have hitherto employed, is not as a result of a decision in any sense lightly arrived at. While your Company has not spent a great deal of money or, up to twelve months ago, of time, on the investigation of the possibilities of the conversion of Malayan timbers, my firm in its private capacity has during the past four years very carefully investigated every phase of the business, from logging to final utilization by the purchaser of the timber, and the whole of the results of this outlay in time and capital has been placed at the disposal of your company. The timber land for which we have applied is not large in area, nor are the stands of timber, as an average, remarkably heavy, and in both respects we could no doubt have done better by going father afield. As against this the area is reasonably accessible from Batu Arang which is the centre of our operations, and the value to this company of a concentration of its activities is calculated to outbalance many disadvantages. The utilisation by your company of modern methods in the extraction and milling of timber should yield interesting results, and if these are as satisfactory as we hope may be the case, the return should be a fair one. While local timber is at present being offered at prices below the cost of production, any material increase in the demand for timber would soon bring prices to a level as high, as the present prices as low. In normal times, not only is the cost of local timber for the better class of work prohibitively high but the quality is such that architects and builders prefer to specify, and to use, either imported timber or substitutes, such as steel Though our main objective in the production of timber for or own requirements and for export, it is considered that an established business, such as that which we propose, may in prosperous times not only have an equalizing effect upon local prices, but also a reducing effect upon the importation into British Malaya of foreign timber.

From the Director's Report of 26 March 1934. Capital work. Erection of wood distillation plant. “... the plywood works was operated full time throughout and at the end of the year arrangements were in hand to increase further its capacity in order to satisfy a demand, which though slow in developing, was nevertheless gratifying. The timber application referred to in our last report was the subject of much correspondence and arrangements are now in hand for a final survey which will enable us to decide whether or not we can meet Government on the outstanding points. The erection of the wood distillation plant was completed and a trail run of about one month’s duration has been effective in confirming the estimates of yields upon which our acquisition of the plant was based. Of the products all but one have been successfully marketed, the exception being the wood preservative on which final teats are nearing completion.”

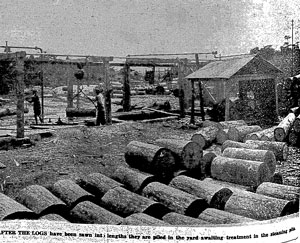

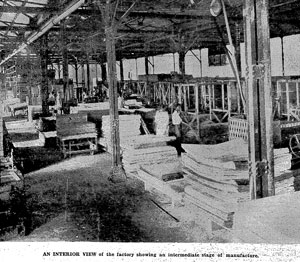

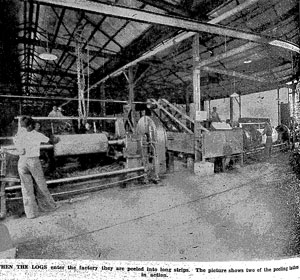

From the General Manager’s Report: Plywood. The production of the works amounted to approximately 4,000,000 sq. ft. of plywood or its equivalent, the bulk of this being sold in the form of rubber chests for which there was an increasing demand. Various alterations and additions were made to the plant as a result of which the capacity of the factory has increased. Wood Distillation Plant. The erection of this plant was completed and a trail run gave generally very satisfactory results. Various modifications have since been made and the plant as it now stands is in every way ready for commercial operation. In the meantime, markets are being developed for the various products and the results should make possible full time operation when the new pilot sawmill is completed, the object being to utilize waste from the sawmill and the plywood works. Timber. Arrangements were made for the erection of a pilot sawmill capable of meeting the entire requirements of the property and of dealing with limited export orders, in connection with which encouraging enquiries have been received. To ensure continuity of supplies of timber for all purposes some three miles of railway was put in hand and practically completed” The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884-1942), 26 March 1934, Page 10

From H.H. Robbins speech at the AGM:“ Considerable quantities of timber are used in the course of our mining operations and in extracting this from the forest, roads and/or railways have to be constructed and a forest staff employed. This being so the way was paved for the extraction of all timber instead of just selected kinds and this gave rise to the acquisition of the of the plywood manufacturing plant. We have always had a sawmill of small capacity and when the opportunity arose to acquire larger and more economical plant upon very attractive terms, this opportunity was taken. Plywood and sawmill plants inevitably produce a considerable quantity of solid waste which normally is destroyed. The avoidance of this destruction and the conversion of the waste into marketable products suggested the wood distillation plant. ...

The demand for the products of the plywood department increased considerably and we can now claim to be established as a generally recognised producer of standard rubber chests which have fully withstood the tests of time. The introductory work on both the technical and the sales sides has not been simple, but the results achieved during the year have fully supported our estimates of the possibilities. Prices have been very keen, but with the general improvement in commodity values which would seem to have set in, this position may soon right itself, especially as prices have not to appreciate very greatly to show us an entirely satisfactory return. The increasing us of alternative means of packing rubber must inevitably continue to effect the consumption of plywood chests, especially where shipments are made direct from the producers of rubber to its consumers. This notwithstanding, it is thought that a demand for chests will continue, especially as it is unlikely that the cost of these in Malaya will ever again approach the prices which were demanded up to two or three years ago. So that we may not be found unprepared in the unlikely event of rubber chests being entirely superceded, we are paying due attention to alternative outlets for our rotary veneer. As a second string, we hope shortly to enter into the production of sliced veneer for general building and cabinet work in this country and in export markets.

The erection of the wood distillation plant, to which reference was made last year, has been completed. A trail run of approximately a month’s duration, checked by a further run which has only quite recently been concluded, has produced quite satisfactory results and it is hoped to put the plant into regular commercial production at an early date. As a matter of interest, I should like to mention that to facilitate the utilisation of the liquid by products of the distillation of wood, we have adapted a part of the plant to the low temperature carbonisation of Malayan coal. To commence with, the throughput is small, but the oils produced will save the importation of similar products and we hope that this will be the forerunner of more important production. The small pilot sawmill to which I have referred, has been erected from materials purchased with the large mill mentioned last year, and this will be used to prove costs and the suitability of products before further capital outlay on the larger mill is incurred.

Negotiations with the Government regarding the area of some 25,000 acres of forest land North of the Selangor River have proved rather more protracted than was expected. Final surveys are now in progress, and we trust that the outcome will make possible the acquisition of the area applied for upon mutually satisfactory terms. The three miles of railway construction to which I have already referred as one of the capital works performed during the year, is an extension of our existing system into the Rantau Panjang Forest Reserve. While its primary object is to serve our current timber requirements, it is along the surveyed route of the line which we hope will eventually connect the proposed 25,000 acres of forest land with the mill at Batu Arang.”

The Straits Times, 31 March 1934, Page 8 and p.9

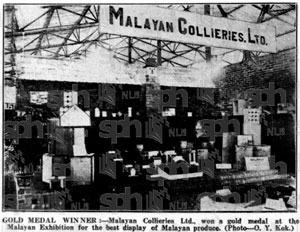

1936 MALAYAN COLLIERIES MANAGERS' REPORT :Subsidiary Undertakings. Plywood department. - The production of the works amounted to about 5 ½ million square feet of plywood, the bulk of which was utilised in the manufacture of rubber chests. Timber. - The sawmill largely met the requirements of the property, in addition to which several parcels of lumber were prepared for the London market. Further extensions of the railway lines were made in order to ensure future timber supplies for all purposes. Wood Distillation Department. - Owing to an accumulation of stocks the retorting operations were discontinued temporarily in November. The various products are satisfactory but progress is slow in establishing them on the market.”

The Straits Times, 24 March 1936, Page 7

H.H. Robbins:22nd AGM in 1936:“ Though we can say that the plywood plant operated practically full time, the stocks towards the close of the year were such as to call for a slowing down of production, and this is still the order of the day. The position is being carefully watched and, though the falling off in demand is due in part to the incidence of restriction, the increasing practice of baling rubber for export is also partly responsible. I should like to repeat that our Malaply chests have stood the tests of time, and to say that never on one occasion, in respect of the hundreds and thousands produced and sold, have we been called upon to pay as much as a cent in claim on outturn. It is important this is generally known, because while we have the competition of the alternative practice of baling, many users of chests continue to use a very much higher priced article than that which we offer. Malaply chests would seem to be an almost obvious course between baling on the one hand and the use of more expensive imported chests on the other. It can be said, however, that a steadily increasing demand exists for our Malaply panels for building purposes. The wood distillation plant ran somewhat intermittently, halts being called at intervals to make it possible for stocks to be cleared or reduced. While this is unfortunate and continually (section missing in original)…… our railway sidings into the selected heads during stoppages are negligible. The plant is in charge of an experienced research chemist, who is always able to employ any respite from routine production in the further investigation of various problems, which it seems reasonable to assume will ultimately give ample reward. The negotiations with the Government for the securing to this company of timber supplies for its various requirements for some years ahead, principally of course those for the colliery, have been brought to a satisfactory close. In the meantime the only further expenditure in this connection continues to be in the extension of our railway sidings into the selected area.”

The Straits Times, 1 April 1936, Page 7

1940 H.H. Robbin's Speech at the A.G.M.

“ A welcome feature of the year was the improvement in the demand for the product of the plywood section of our undertaking. When last addressing you, I referred to the more satisfactory progress that was being made in the wearing down of conservatism on the part of users of chests. As a result of this hopeful trend, it was decided to avail ourselves of an offer of plant which promised an increase in the productive capacity of the factory of the order of 50 per cent. When the war came, the erection of this plant was almost completed, with the result that we were able to respond in a much more ready way to the demand created by the shutting off of supplies of chests from Baltic countries. I have previously remarked that if the principle of support to local secondary industry in normal times is regarded by some as controversial, there can be no argument about the value of the production of such local industry in time of war. In conformity with this principle, we are still expanding the plywood plant, so that we may be in a position to take care of the full chest requirements of the Malayan rubber industry, if such should come our way. As an instance of the value of the plant to the rubber industry and to the country generally, I might mention that imported chests of no greater intrinsic value than MalAply, are being sold in this market at well over $1 each above our average selling price to estates this year, and at fully a dollar more than the average price at which we are at present offering our chests to users for delivery next year. Such sales are helpful in assessing the value to the Malayan rubber industry of the local production of plywood. This, on the basis of a million chests sold this year, would seem to be not less than $1,000,000 actually saved, while, judging by the trend in bookings for next year, the saving should be nearer $1,500,000; or $2,500,000 saving to the rubber industry in only two years. Perhaps an even greater benefit to Malaya from the use of the MalAply chests is the resultant saving in foreign exchange which, for 1940 and 1941 alone, would appear to be in the region of $6,000,000. These are big figures, and while they do not accrue to the benefit of the industry and the State without the retention by us of a satisfactory profit on our capital outlay and to cover the risks and responsibilities assumed, we do feel that we are, to put it on a purely business basis, making a definite and practical bid for a continuation of support when more normal conditions return. The sawmilling plant was re-housed and largely re-equipped and, after supplying the colliery requirements of sawn timber, it is fully manufacturing battens and planks for the plywood section. The brickworks plant and wood distillation plant were not fully employed. The demand for brick was checked after the outbreak of the war, due principally to the shortage of cement for building purposes. The war has set up an improved demand for MalAsote wood preservative one of the principle products of the wood distillation plant, but because of the difficulty in disposing of the charcoal at remunerative prices, the operation of the plant remains intermittent. "The Straits Times, 30 March 1940, Page 4

The workforce of the Plywood Mill. Extract page 10

The first couple of weeks I used to familiarize myself with the general conditions in the mill, pick up as much as possible of the language generally spoken, the so-called pigeon-Malay, and to learn to know the different persons of the work force, their names, appearances and working qualities - and that alone was quite a task. 10 About fifty percent of all the mill workers were Chinese, about forty per cent were Indians and the rest were Malays, plus a couple each of Siamese (Thais) and Sakais. The Sakais were the jungle people of Malaya. The Chinese were of three different nationalities, the Cantonese, the Hylams and the Kehs. They all had different features, dialects, habits and working qualities. The cantonese usually were the ones best educated and three of my office staff and the two leading fitters were Cantonese. The Hylams were mainly employed in the packing section and besides, nearly all the house servants employed by the Europeans in Batu Arang were Hylams. The Kehs were employed in the gluing-, taping- and drying section and they were supervised and paid by a Chinese Kepala or contractor (kepala = head in Malay). The Indians were also in three groups, the Tamils, the Sikhs and the Moslem Punjabis. The Tamils, originating from Southern India, were mainly working in the packing, peeling and drying sections together with the Chinese. The Sikhs and Punjabis, who all were well built and strong people, were carrying veneer waste to the boilers and were filling and emptying the log vats. The Malays were mainly employed as operators of the lighter machinery and as tally clerks - and most of the better paid Europeans had a Malay as driver and in charge of their car. The Malays were friendly and intelligent people, but did not fancy much being tied down to heavy factory work. Having people of so many different races and religions and with so many different habits and viewpoints working in the same mill and living, so to say, on top of each other in the village, naturally caused a few complications and problems. One Sunday afternoon when I was down in the timber yard for inspection of some plywood logs I could hear there was quite a commotion over in a couple of the nearby barracks occupied by some of my workers. I went over to investigate and found a laughing crowd of Chinese crouched in front of some of the rooms occupied by Malay families; the Chinese were eating pork in a very demonstrative and noisy manner. This was, of course, an offence and a direct challenge to the Malay Moslems, and a proper fight would certainly have developed if I had not arrived in time and ordered the Chinese to clear off. After this experience I arranged for separate barracks for the different races.

1935- 1939 The Mill Extract page 7

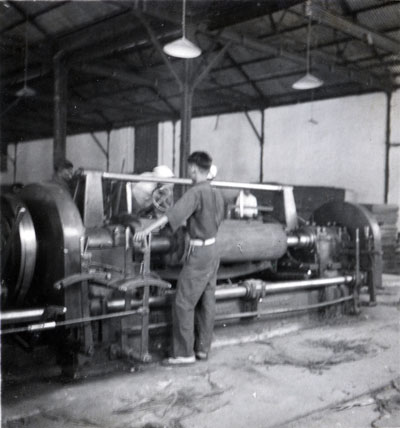

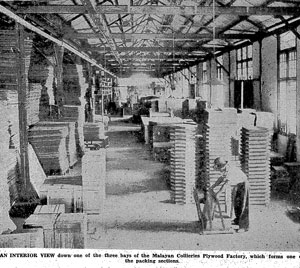

"Already the following morning I was taken down to the plywood mill to have a quick look through the place I should soon supervise and I could see right away that I would have a rather tough task ahead of me, remembering the well laid out and modern plywood mill in Kristiansand, Norway, where I as an assistant work superintendent had given five years of service. The plywood mill in Batu Arang had been started up in 1932, based on an old peeling machine and some additional machinery taken over from a German match factory, which, failing to produce a good match-head, had gone bankrupt. Gradually more machinery was added on until we in 1941 had five peeling lathes, two hot presses, three guillotines for cutting plywood into shooks, three taping machines, two sanding machines and one about 200 feet long steam-heated progressive veneer and plywood drier with six rail lines with trucks loaded with veneer and plywood. One big Babcock & Wilcox boiler and a smaller Cochrane boiler provided the necessary steam for the kiln, the hot press and for three bigger and three smaller log vats. Due to the gradual building up of different machinery the placing of same had been somewhat haphazard and congested, specially so because no separate store-room was provided for until 1939, when such a building was erected."

Working Hours. Extract page 8

"All the different operations in Batu Arang were continuous operations -seven days a week, night and day. The only complete shut-down officially acknowledged was under the regular four days Chinese New Year celebrations in January. Then we had a couple of partial shut-downs for a day or so during other native celebrations. But for the European staff it was also hard and steady work, often with very long working hours. We had a six-and-a-half day working week with half a day off every Sunday afternoon, when we could manage to take it, and there was no other official leave. However, this was gradually improved upon and from 1939 we had as much as ten days local leave a year, plus two days off every month."

.jpg)

1950 From a booklet produced by the Colliery after the war.

Plywood Factory: This had been built up over some years into a large and efficient organisation providing Malaya's rubber and tea industries with a large proportion of their packing requirements at prices competitive with imported chests. Incidental products were pineapple cases and building panels for walls, ceilings, doors, etc. The large quantity of logs required to keep the peeling lathes busy was obtained partly from the Company's timber concession and partly from as far afield as Negri Sembilan. 1941 was a prosperous year and 1942 held promise of being still more successful. Large quantities of casein for glue making and other incidentals had been accumulated to meet a record demand. These stocks fell into the hands of the Japanese. The invaders made poor use of the plant and material and left the Factory in such a sorry state that, due to the difficulty of replacing machinery in a post war world and the necessity for giving priority to coal production, it was considered impracticable to proceed with rehabilitation of the Plant. With the cruder but effective means of packing rubber now in force (known as " bare-backed baling") it is doubtful whether plywood chests will ever again be employed for the purpose.

' Wood Distillation Plant: This produced methyl spirit, wood preservative and acetate of lime, with charcoal as a bye product. The Plant was left by the Japanese in the same dilapidated state as the Plywood Factory and for similar reasons any idea of its revival has been abandoned.

The Company's wood distillation plant was situated about 150 metres away from the plywood mill. A well educated Hindu Indian of high caste was in charge of the plant. His name was Hari Harrahn. We often met and had many interesting talks and discussions covering all kinds of topics. 11 discussing the quality of the casein glue we used for plywood, he asked me what kind of glue we had used in the plywood mill in Norway, while I was working there. “0h yes,” I said, "when I worked there, they used a mixture of casein and blood albumen together with a few other chemical items.” Then I saw how the blood went to his head and in a fit of rage he cried out: "What a cruel thing to do; fancy using the blood of all those beautiful cows, when you had all you wanted of first class casein.” Realizing that I was talking to a sincere Hindu, I made a hasty retreat, saying that they surely must have changed the formula since. This little episode made me even more aware of how careful I had to be not to hurt somebody’s feelings in this country of many races and religions. I did also find out, however, that the caste system was used by many as an excuse for not carrying out certain kinds of work. Every time I engaged a new worker, never mind what race he belonged to, I gave him as his first job to sweep the factory floor, this to find out if he was a willing worker. In a couple of cases the Indian worker concerned told me that he could not sweep the floor as that was the job for a low caste Indian. I told him then that he was too good for me and had to find work elsewhere. In both cases they found they could sweep the floor after all.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Discipline

As the mill progressed the working force was increased and, as previously mentioned, a good 400 men were employed by 1941. When we moved over to the 12 other bungalow, situated in the very proximity of the plywood mill, evening and night control became much easier for me, but the dodging during night hours was still a problem, although on a considerably reduced scale. Coming down one night I could see a black shadow among some big stacks of one inch square battens supplied for rubber chests in the packing section. I pushed over one of the stacks and up came the sleepy and frightened face of a Malay. It was hard for me to keep a straight face looking at his expression of surprise. With a warning of "next time out of the gate you go", I left him. The same warning another of my night workers got a few days later, when I was down on another night inspection. In a corner, where we had a few ready assembled samples of rubber chests, I observed that one of the chests had a rather bulky appearance with the lid placed haphazardly on top of it. I banged my fist hard on top of it and up jumped a small jet black Tamil like a "jack in the box", and with a persuasive smile he called out: "Tidak tidor Tuan." (I am not sleeping, sir). These and other incidents made me realize that I had to treat the natives as naughty children. I also remembered what I had read in a book a long time ago. "If you through patience and understanding can gain their hearts and their loyalty you have come very far." This was why I did not want to rush into things. If I did so without even being able to speak the ruling language, Pigeon Malay, properly, and without knowing their habits and views of life better, I could do a lot of harm to my own prestige and a Tuan without prestige would never get along well with the natives. Each of the three eight hour shifts had a native foreman or supervisor. They were good and intelligent people, but the discipline they kept was rather slack. They did not dare to antagonize the work force too much, specially in cases where other races were involved, as this would quickly lead to accusation of discrimination on the one side and favouritism on the other. So all kinds of disciplinary action I had to deal with myself. So one evening I came home very late after a trip to Kuala Lumpur. I went straight down to the mill and found four of the workers sleeping. As first time offenders I gave them all another chance and went up to my bungalow, where I after a few minutes put out all the lights and seated myself in the mosquito-room. After half an hour in darkness I went down and re-entered the mill, where I caught two of the previous offenders again soundly asleep. I sent them home and told them to collect their pay envelopes the next day. This kind of cured the desire for sleep during night shift and I had also in the meantime engaged a permanent night watchman (jaga) to patrol the mill at regular intervals and call me whenever he found it needed. 13 The jaga, a Sikh, was quite keen on his job, sometimes a bit too keen till I had familiarized him with what was worth calling me for. But even so I had frequent night calls. I can recollect that at least twice I was called three times during one night. This kind of turned me into a light sleeper and Jaga had only to come outside my open bedroom window and in a very low voice call out "Tuan". It was very seldom Molle woke up during my "night escapades." Although there were so many people in the mill there were amazingly few cases of theft. I will only relate one instance which I remember so well, also because I felt so sad about it. On one of his night rounds Jaga had observed a Tamil leaving the mill carrying a bag of limil over to his little attapa house close to the wood distillation plant. It was a Tamil by name Katerasamy, a nice looking, quiet young man who was married and had just got a son. When I came down to my office the following morning the theft had already been broadcasted in the mill and I sent a message to Katerasamy to come and see me. When he arrived I asked him why he had taken a bag of limil from the gluing department and carried it over to his house during working hours. "No, Tuan, I have not taken anything. I am a Christian so I cannot steal," he said and pointed to a silver cross he had on a thin chain round his neck. "You do not make it better as a Christian to add a lie to your pilfering, Katerasamy," I said; "we'd better take a walk over to your home and have a look together." As we started walking I could see he became very uneasy and he soon turned to me and said: "I did steal the bag of limil and I have also taken another one, Tuan." As the whole mill by then knew about it, I had to take proper action and Katerasamy was sacked straight away. But I paid Katerasamy a month's salary as a gift to his new-born child. My Indian pay-clerk managed to find him a job at a nearby rubber estate a few weeks later. With so many people working and with the relatively poor safety precautions taken, coupled with the rather little respect the natives had for human lives, a few serious accidents could not be avoided. The Sikhs, employed on the heavy log work, unloading logs from the railway trucks, pushing them into the steam vats and later hoisting them out of same, were the ones most exposed to accidents and during my first four years term I was four times called down during the night shift to attend to serious accidents. Twice, and in both these cases a Sikh was involved, the accident was fatal, due to third degree burns on the body, when the man dropped head-on into the boiling vat. Molle always kept a couple of sterilized bed-sheets ready for emergencies and the ambulance was quickly on the spot. It was very 14 sad and depressing to witness the pain and despair of the victim. The three bigger log vats were each surrounded by a concrete elevation and the three smaller vats were covered by solid wooden boards during the steaming of the logs. The whole log-yard was well lit up during the night. This was also necessary, as many of the workers used the log-yards as a short cut on their walks to and from the village. One evening I was called down as one of my Tamils, by name Krishnan, had fallen into one of the smaller log vats, while the Sikhs were emptying it of logs. He was badly scalded from the hips down and I immediately got him over to the hospital, wrapped in a bed-sheet. After a few weeks of treatment Krishnan recovered completely and then left Batu Arang. About a year later Krishnan reappeared outside my office. "Do you remember me, Tuan?” he asked. "Yes, Krishnan,” I said, "and how are you getting on?" "I have a confession to make, Tuan, and 1 hope you will not be too angry." I asked him to ease his mind and tell me everything and he then related how his accident had occurred: After work he had gone down to the village, met some friends and together with them he had consumed some samsu (native alcoholic drink) and they all went home via the log-yard. Passing one of the small log vats, just opened for removal of ready boiled logs, he wanted to show off how good he was in long jumping - so he jumped and landed in the middle of the vat. Luckily the steaming logs prevented him from being immersed in the boiling water, but, badly scalded, he was quickly rescued by the two Sikhs at work. By giving a false report about how the accident happened he received the usual compensation money from the Company during his convalescence period, but his conscience had worried him every since. I asked him if he wanted to start working for me again and a broad smile gave the answer. Another of my really faithful Tamils I picked up along the rather steep jungle road at the outskirts of Batu Arang. As often as time did permit it I had a short evening walk on the jungle road leading into the village. Just at the entrance was a small hut, where a Sikh jaga (watchman), who had telephone connection with the local main office, controlled and booked all traffic in and out of the village. I enjoyed the peculiar and wonderful feeling in witnessing the jungle "going to sleep"; half an hour after sunset it is all enveloped in pitch darkness. I had just passed the gate when I saw a Tamil on a bicycle, travelling at rather high speed and using his bare feet as brakes 15 on the front wheel with only limited success. When he was just about to pass me, I to my horror and surprise saw him jumping off the bike, and as he was unable to keep his balance he dropped in front of me, rather badly shaken and bruised. I asked him in Malay what the heck he did that for and became rather surprised to hear the answer: "I cannot pass a Tuan sitting on a bike, I have to pass him walking. My bike has no brakes, so I fell off." He had come to Batu Arang to see a friend. He himself was working at a rubber estate further up at Selangor River, where the discipline evidently must have been somewhat harsh. I helped him up, took him to the Mill and cleaned his bruises, bandaged him and sent him over to Dr. Dason, the nice Indian doctor at the hospital. As the Tamil had friends and relatives working in Batu Arang he soon afterwards joined the work force at the plywood mill."

Time line of the invasion:

• The Japanese invaded on 8 December 1941 at about the same time as their attack on Pearl Harbour.

• They sank the British battleships HMS Repulse and HMS Prince of Wales on 10 December.

• They reached Kuala Lumpur on 11 January 1942

• The British retreated to Singapore on 31 January

• Civilians were evacuated from Singapore in February, while suffering bombing from the air.

• Singapore fell by 15 February.

• Guerilla resistance forces fought the Japanese from the jungle.

Making a table for Mr. Drysdale.

Next time Mr. Drysdale visited the plywood mill and saw the beautiful teak plywood he asked me if I could make a big round table-top of eight feet diameter covered with teak plywood. The table was to be used in Kuala Lumpur at a garden party given for a prominent businessman. I decided to make the table-top with a two feet centre consisting of a sixteen sided diamond of red meranti with sixteen stripes of matched-together teak plywood branching out from the diamond. The whole surface of 5-ply to be glued on to one inch thick solid wood. I sent for Chan Chung and told him about how I wanted the table-top made and that I would construct on paper a pattern for the sixteen segments which were to make up the outer part of the table-top. It did not take me very long by means of a drawing compass to make the sketch and I took it out to Chan Chung's little carpenter's shop to show him. When I saw him he just quietly said: "Sudah bikin, Tuan." (Already done, sir). He had already cut a pattern in veneer, covering exactly one-sixteenth of the circumference. I have often been sorry that I did not ask him how he with apparently only primitive means had managed to make the pattern so fast and exact. Between them, Wong Choon and Chan Chung made a beautiful job of the table, which was much admired by the guests at the garden party. I have seen much beautiful straight grained and figured veneer peeled from logs from all five world continents, but none of them have surpassed teak veneer in appearance when you are lucky enough to strike a log of A1 quality. The enchanting golden brown colour playing in different shades and figures gives an exhibition of extreme beauty over the complete panel.

Visitors

Soon after Christmas we had a couple of interesting visits at the plywood mill. Mr. Drysdale rang me up one morning informing me that he was taking with him Sir Thomas, the then Governor of Malaya, and also some of the Governor's executives, to have a look at the mines and the plywood mill. They would arrive at Batu Arang in an hour's time and as the plywood mill was lying next 55 to the road of entrance this would be their first place of call. The said telephone message resulted in a feverish activity of preparation and cleaning up, specially round the four peeling machines then in use. The Governor was on one of his familiarization trips and Mr. Drysdale asked me to give a good demonstration. When the party arrived the mill was nearly suspiciously clean and four selected logs were ready fixed in their machines and already peeled round and smooth. As the visitors entered the mill I gave the pre-arranged signal and four peeling machines were spitting out layer after layer of fine veneer. Sir Thomas shook hands with me and gave me a few friendly words and by an acknowledging nod and a smile I understood Mr. Drysdale was well pleased with the demonstration. Another visit of more personal interest to me was paid by Mr. Harold E. Desh, a highly educated English scientist, who was in charge of the Forest Research station at Kepong, Selangor. Mr. Desh was very interested in the different woods we used for veneer peeling and a friendship between us developed, based on our common interest in and love of trees and wood as a material.

Increasing production for the war effort.

Due to the war in Europe, rubber became a raw material of vital importance for the Allied war machine and for U.S.A.'s war preparation, and consequently rubber chests were very much in demand. I managed to increase the production from 60 000 chests a month up to 80 000, but more were wanted and I was under constant strain. My native workers certainly were loyal and hard working and I felt rather warmly for them all. In Batu Arang as in the rest of Malaya one started feeling in different ways some effect of the war in Europe. Quite a few merchant ships bringing supplies of different foodstuffs, machinery and industrial necessities from Europe and America were sunk by German submarines and raiders. Also in the plywood mill we ran short of certain items but by taking various precautionary measures and by introducing some emergency steps we managed quite well. Old peeling knives and guillotine knives earlier discarded, but not thrown away, were taken into use again and used to the very limit of their usefulness. Now that no complaint over slightly rough surface would come in, we eased the pressure of the sander rollers and thereby made the sand paper last longer. In a rather amusing way we solved a temporary shortage of taping paper, used for taping our veneer strips into full sized sheets, this being a must for the maintenance of top production. The strips were piling up out in the mill and I was sitting in my office wondering how to solve the rather tricky veneer strips problem. As I was sitting like this my eyes fell on the small stapling machine on my table and in the next minute I was out in the mill 68 stapling some veneer strips together. As the guillotines only cut along side and across the centre of the sheets plus along the edges, we could easily arrange the stapling in such a way that the guillotine knives did not come near the staples. We only had to arrange the spacing of the staples in the right way and select strips of suitable width to overcome the problem. The following day we received quite a load of paper staplers from Kuala Lumpur and we kept the new process going till we a couple of weeks later received a new supply of taping paper. It was just a lucky coincidence.

1937 End of the slump and the Chinese workforce.

Gradually business seemed to work its way out of the slump and by 1937 rubber had slowly but steadily come more in demand. Consequently, the sale of rubber chest shooks also increased; we let the production follow step simultaneously as we got rid of a lot of surplus stock piled up in the mill. I really became more and more fond of my work and so also of ay native working force. Not once during all those years - seven and a half years all told - did I hear any insulting remarks or hear any complaints about driving them too hard. An important thing I also learned was that among all these people, who rather derogatorily were called coolies, we would find some very brainy fellows with a lot of pride and self respect. The kepalas (heads), leaders of the different labour gangs, were experienced people with a lot of authority behind them. My head fitter, a Chinese by name Ah Lok, looked after all the machinery in a very efficient manner. During my years among plywood machines I had learnt to listen to them during their running and if I heard something irregular I pointed it out to Ah Lok, who always found the source of the trouble. In more difficult cases we had to call for the engineers at the big and well equipped workshop in the centre of Batu Arang. I had two Chinese kepalas in my service, both of them clever and trustworthy people. Wong Choon, a happy, jovial and hefty-built Keh, was in charge of the gluing operation and also arranged for labourers whenever we needed extra help in the taping and drying operations. He had quite a few Chinese, all Kehs, working at the mill and they all lived together in a small compound of barracks -in a "kongsi", where Wong Choon provided food for them and their families on top of their pay. My other kepala, Chan Chung, a small, polite Cantonese, was in charge of five carpenters, but the latter were paid directly by the Company. Chan Chung never failed to do first-class workmanship. At the time I took full charge of the plywood mill we still used a brand of rennet casein, supplied by an English firm. This casein gave us a fair bit of trouble due to uneven quality. One smaller consignment which we had stored for some time because of its doubtful quality, had to be used when we, because of shipping delay, had no other stock at hand. Wong Choon and I spent the whole day together trying different ways and means in attempting to obtain a workable glue, but we did not have much success. The following morning I cane down to the mill round about six o'clock and to my surprise and joy I saw 34 Wong Choon and his gang gluing away as usual. With a broad smile he called out: "Ada baik sekarang Tuan." (It is all right now, sir). After a bit of persuasion he revealed his secret. A friend of his had advised him to add some cooking salt to the formula and that was tried out in different proportions by Wong Choon till he achieved a reasonable result. We were able to carry on till we a few days later received a fresh supply of better casein. It was rather a good effort by my kepala, whom I always found keen and alert. Some months later we changed over to Australian clean latex casein and this gave us a very strong and reliable glue joint. After I had worked at the mill a couple of years we received a small consignment of teak logs (Tectona grandis) from Burma. I spent days matching the veneer from this superb veneer timber and we glued some very nice 5-ply plywood from it, beautifully figured with a rich golden-brown colour.

The memoirs of Thiel Marstrand continued: 1941 The Japanese Invasion. From then on there was not much time for private life. Molle used nearly all her time sewing and knitting for ourselves and for the Red Cross. My time was shared between work at the mill and military training on the Company ground and the going was tough in both cases.

From Kuala Lumpur we received orders for all European women and children to leave Batu Arang within the next couple of days, take with them the bare necessities and proceed to Singapore by train or by car. Molle and Valborg left on the 27th December and were among the last few to leave. Before this happened we were clinging to a feigned hope of improvement in the situation. We carried on with intensive military training and took guard duty in the power station, main store and other important places which could be subject to sabotage or looting. This involved a certain amount of night duty, which was carried out in pitch darkness after orders about complete 83 black-out of the area had been received. The wheels were still running both in the mines and the plywood factory, but the production decreased daily due to the decreasing morale of the natives which was quite explicable and also due to the increasing visits by Japanese planes.

The British Army Arrives.

A couple of days later British military arrived in Batu Arang and we were told all of us to meet at the Police Station where we should have our quarters the next few days. Soon after we had arrived we were told that military experts were going to blow up the Power Station. As this happened it also became a signal for the looting to start and we were told to stand by showing a passive attitude so long as no violence took place. The few remaining policemen, mainly some fine and loyal punjabees, were in a smaller building close by, while 26 of us, all Local Defence people, were crowded together in a rather small room in the main building. We entered the room after some additional hard training and during the day I had obtained special permission to go back to the plywood factory and my bungalow to have a last look - all under the definite understanding that it was under my own responsibility and risk. I had my loaded rifle with me and felt quite safe. I took a short cut through the Chinese quarters and to my joy I only was met with some friendly "goodbye Tuan", from some of the families living there. As I arrived at the plywood mill many people, including quite a few of my workers, were carrying all kinds of items away and I told some of them to secure some of the good Australian casein, which could be quite suitable for porridge if need be. My bungalow was already stripped completely...

Leaving Batu Arang

Already the following morning we left Batu Arang. Our personal belongings, whatever we had managed to save of them, were loaded on one lorry and in some of the private cars and in a couple of trucks and all of the Local Defence members were placed more or less comfortably in private cars. Twice Japanese 86 planes circled over us and we were ordered out of the cars to take shelter in the dense jungle surrounding the road. Nothing happened however, and a few miles further down, near Kundang Estate, we settled down for the night. We were all detailed certain guard duty, but made as comfortable as possible in three deserted bungalows, which all had been thoroughly ransacked by looters. Broken glass and bottles, torn papers and smashed up inventory were all which was left of the previously nice and well equipped homes. We stayed there another day till we were told to proceed to Kuala Lumpur.

In Singapore

I was having a quiet walk in the garden, when I saw four Sikhs approaching me. As they came closer I recognised two of them straight away. They were Inder Singh and Sundar Singh, bringing two of their friends with them. They rushed forward to me, went down on their knees and grabbed my hands: "Please come back to us, Tuan," Inder Singh said. "We need you and we miss you and we have no work and will soon be starving." I told them that I could not go back to Batu Arang as nobody without special permission could leave Singapore and that disobeying such an order only would result in severe punishment. Then they told me that some picked people of my previous labour and office staff had approached the local General Superintendent in Batu Arang, Mr. Kuda, a Japanese representing the powerful Mitsubishi Company. They had asked Mr. Kuda if he kindly could arrange to bring me up to Batu Arang. Mr. Kuda then said he would agree to their request provided the military authorities would sanction it and I would obey by the rules and orders laid down by his 108 Company. And Mr., Kuda had added that it also, of course, depended on whether Mr. Marstrand would like the responsibility of looking after them and whether he is found suitable to do so. All this Indar Singh and his three friends told me and they had come down to sound me out and prepare me for an eventual interview by a military authority. In a kind of a daze I told my four friends that I would take the risk and come up and help them, but that I could not promise or forsee what I could do for them all and how long I would last up there. My four Sikks left me with the assurance that all of my old friends in Batu Arang would be loyal to me and would never give me away whatever I did.

"Running" the Plywood Mill under Japanese occupation. Next morning I went down to the mill and there I found nearly all of my old office staff waiting for me. It was with rather mixed feelings I met them, but my mind soon came to rest when they all pleaded their loyalty to me and told me that they only wanted money for daily bread for themselves and their families and hoped I could help them in securing this. We all agreed we should be very careful in all we said and carried out and just hope for future better days. They told me about the military garrison stationed in Batu Arang, supervising order and discipline in a strict way, but that they all had found Mr. Kuda a nice person, who did not want any cruelties or personal persecution so far his authority could prevent it. When I somewhat later went over to see Mr. Kuda I had a working proposal to put forward to him. Mr. Kuda greeted me with a hand-shake and asked me to sit down. (By offering me a seat he wanted to show me courtesy). He was very nice and said he could quite understand my feelings coming back and seeing the place in such a state, but he wanted to help the natives making a living and, as so many of them had uttered the wish of seeing me back, he had yielded to their request. I told him about all the logs which were lying on the bare ground in the mill yard exposed to attacks by fungi and insects. If they all were cleaned and stacked on wooden rail supporters most of them would still yield good veneer and that quite a few of my old workers could be employed in this way. Mr. Kuda asked me to go ahead with it and for my fitters to clean and repair 113 different machinery partly demolished or destroyed before the British evacuation. As I was sitting there talking to Mr. Kuda, I could not but like this friendly and rather handsome man, who no doubt first of all had his own country at heart, but at the same time he wanted to help the native population. As time went on it was he and Mr. Chichio who stopped other Japanese from punishing me severely in spite of the fact that they could not avoid detecting the real feelings I was hiding in my heart. During the following couple of weeks many of my workers, some of them just arrived after they had heard about my return to Batu Arang, were kept busy cleaning and stacking logs under the supervision of Kiang Yoong and myself. I remember that we in a rather wet corner killed close to a dozen big, black scorpions and afterwards we were somewhat more careful in inspecting the logs before we handled them.....

Beaten by the Japanese.

When we nearly had finished stacking the logs, I went over with another proposal to Mr. Kuda. I told him that all the logs now were neatly cleaned and stacked, so they were ready to be sorted out according to colour, quality and condition. I knew before-hand that I took a "calculated risk" coming with such a proposal, as all this could have been carried out in one operation as we were stacking the logs. But it would mean another couple of weeks work for all of us, so the risk was worth taking. Luckily Mr. Kuda agreed to it without any comments, but I had a little sting of bad conscience because Mr. Kuda was such a nice person. As we were on this second bout of log rolling I was asked to come over to Mr. Kuda as quickly as possible. I had in the meantime been provided with a bike, so it only took me 5 minutes to come over to there - and of course, I had not the best of conscience. Arriving there I was told that Mr. Yoda, Mitsubishi's No. 1 in Malaya, wanted to see me. When I was called in to Mr. Yoda I managed a small bow and seated myself on the chair opposite to him. Through his interpreter Mr. Yoda told me that I had to stand when I was talking to him. I think Mr. Yoda saw how confused I became for he looked at me with ever so little of a smile. He then told me that I would receive a monthly salary equivalent to half my pre-war earnings and I could see how he was watching my reactions. I just half whispered a "thank-you", but could not show any kind of joy. I did not want any of their "banana money", but I had to live with it and of it while I was up in Batu Arang, as I had no other source of income. But the few times I met Mr. Yoda he was treating me correctly, nearly friendly. This I certainly could not say about another of the Japanese officials whom I regrettably quite often had to encounter. Mr. N. was supervising the engineering department and the power station. He was a most unpleasant person and he clearly disliked me because of the colour of my skin. First time I met him was when I brought a requisition for some machinery tools for him to sign. Mr. N. cross-examined me about what I wanted to use the tools for and it all went through an interpreter, as he could not speak or understand a word of English. Finally he put his stamp on the requisition and angrily waved me aside. My old Ghurka friend, Apanah, who was back on his old job in the engineering department came after me when I went out. "Do not worry about that nasty b.. Mr. Marstrand," he said. "Next time you require anything from the store, just give the requisition to me and I will put it together with all the other daily requisitions we are bringing for him. Mr. N. cannot read them so he sits there stamping the whole bundle one by one with the speed of a piston pump." A good advice from a good friend. 115 The same Mr. N. had already at that early stage practised ear-slapping both on his native as well as his Japanese subordinates. One day there had been a fight in the village near my bungalow and I was called over to Mr. N. who told me it was my duty to report all irregularities, if not I would be punished. What a nasty man he was! Soon after this I was sitting in my mosquito room just after work when I heard a sharp shot down near the drying room. I went down immediately and found a very nervous Sikk watchman outside the drying room. He was placed there by the Japanese to ward off possible sabotage of the explosives inside. The Sikk was standing there leaning nervously on his shot gun. I asked him what had happened and in a stuttering voice he told me that as he was patrolling outside the drying room area he had surprised a Chinese who was acting rather suspiciously. As he started running away he had fired two shots after him, but missed. I told the frightened Sikk to wait ½ an hour till the relief watchman would arrive and then we would go over to Mr. Chichio and report the matter. "But I want the whole story and you'd better tell me the truth, if not I cannot help you," I told him. "I only heard one shot, and I do not think you saw a Chinese either." The relief watchman arrived and carrying the empty shot gun I took the Sikk over to Mr. Chichio's bungalow, as it was after working hours. I carried the shot gun so the villagers should not think that I had been arrested. On the way I got the full story out of the Sikk. He had simply become somewhat fed up on the job and had started fingering with his shot gun with the result that both cartridges were fired simultaneously, barely missing his head. Mr. Chichio was very friendly. He asked me to sit down and share a soft drink with him and promised that nothing would happen to the Sikk. But something should happen to me. Next day I was called over to Mr. N.'s office and I was wondering what he had in mind this time. As I entered the office a very angry Mr. N. stood ready for me. Next to him Captain Kami, the military supervisor, not connected to the garrison, was sitting in his chair. At my entrance the Captain dramatized the situation by pulling his pistol out of the holster and put it on the table ready for use. "Why did you carry a rifle yesterday?" Mr. N. barked out. "It was no rifle -," I started, but I was interrupted by a hard blow right behind the left eye. Two more powerful blows followed in quick succession and painful as the blows were, I remembered the pistol on the table and the danger in any resistance. Luckily Mr. N. stopped 116 after his third blow and half dazed as I was I felt a certain pleasure in thinking of his sore fist. "If you report this to Mr. Kuda you will be in serious trouble," Mr. N. warned me. I went straight over to Mr. Kuda and told him the whole story. Mr. Kuda thanked me for telling him and told me he should deal with Mr. M., as he would not tolerate any beating going on, specially under unfair circumstances. I was later complimented by Dr. Dasen and others of my friends for having put a brake on Mr. N.’s beating practice. Mr. Chichio told me that Mr. N. had been reprimanded by Mr. Kuda - and I hope it was in the Japanese way. In the months to come I did not have any real confrontation with Mr. N. but the few tines he passed me he sent me some angry glances and shouted "Bugger", one of the few English words he had picked up. In the meantime we rolled and stacked logs and more logs and we had also in the meantime been busy with stock-taking of plywood sheets and shooks left over and not looted after the British retreat. The fitters, under Ah Lock's care, had fixed most of the machinery back to running condition. Unfortunately for my mill staff and for myself it went as I had suspected. We would not in the long run be left so much alone, working but progressing very slowly and not producing anything. Sometime before Christmas Mr. Ukawa, a Japanese plywood expert from Japan, arrived and a much tougher time was ahead for all of us.....

February 1943

One event which could have had some nasty consequences for the Chinese working in the mill if it had not been for the quick-witted action of one of them, is worth telling about. One morning two cars and a lorry arrived at the plywood mill. In each of the cars there were three Japanese plus their Malay driver. Two of the Japanese were strangers from Kuala Lumpur and in one of the cars my old "friend" Mr. N. was seated. He brusquely ordered me to enter the lorry next to the driver and off we went. The lorry driver was an Indian, who for years had been driving the sane lorry pre-war for my old Company and we had also during "the new order" often exchanged a few friendly remarks when he delivered goods to the plywood mill. Being only the two of us in the lorry we could talk together freely, while we were heading for a rubber estate about 20 miles away at the Selangor River. The two cars with the Japanese were in front of us. The driver told me that he never felt at ease, as Mr. N. was his boss and he was always very suspicious and came with all kinds of impertinent questions, "and he told me not to talk to you," he added with a laugh. This was in February 1943 and we had heard about a few set-backs for the Japanese and that the guerilla forces in the jungle had become more active. "But the guerilla forces will not attack Batu Arang, Tuan," said the driver, "there are too many civilians who will suffer if that happens." As we arrived at the rubber estate, which was supervised by a nice, youngish Eurasian, a number of 44 gallon drums filled with latex were loaded on the lorry, while the Japanese took a stroll round the plantation and factory. The young Eurasian approached me and said he had heard about me through some friends of his and he could imagine how lonely and unsafe I would feel being the only European in Batu Arang surrounded by the hostile Japanese. "I realize you cannot run away without any direct provocation, as that will mean severe trouble for your workforce," he said. "But should it ever turn out so that you have to escape in a hurry, you find your way up here and we will look after you and keep you in hiding." I thanked him so much for his kindness and we shook hands The Japanese soon came back and we started on the return trip, but not before our friend, through a small Indian boy, had handed a nice bunch of bananas to the two of us in the lorry. 121 Coming back to the plywood mill, the driver and I were shocked to finding the entrance blocked by Japanese soldiers with rifles and fixed bayonets at the ready and three light machine guns pointing towards all my Chinese workers, who were lined up in front of the building. I was told by a Japanese interpreter to go and sit down in my office and stay there till further orders. There I also found my office staff, all very concerned and uneasy. They told me that the Japanese had discovered some abusive writing inside on one of the drying room doors. The following was written with black crayon in Chinese letters: “We must get rid of these nasty foreigners." The Japanese had lined up all the Chinese working inside the plywood mill and insisted that the writer of the above words should come forward and confess and take his punishment (which no doubt would be a terrible one). The soldiers had already gone along the line of Chinese and given each one of them a slap or two on the ear. The situation was very tense, but suddenly the Chinese were allowed to leave and the soldiers were marched home to their barracks. Then we heard how one courageous and quick-witted Chinese had stepped forward and told that he had seen the writing on the door before the war started, which meant that the abuse was directed against the British. Luckily this interpretation was straight away accepted by the Japanese, who thereby avoided a long and difficult interrogation, and they saved face and even triumphed by seeing their enemies degraded. Later on 'Wong Choong very confidentially told me that he knew the abuse had been written very recently and for the "benefit" of Japonpunya orang (the Japanese). Of all the nice and helpful people I met in Batu Arang, my old timber clerk, Chung Kiang Yoong, was outstanding in his loyalty and friendship and I will always remember him with sincere gratitude. He was also the very secret mediator between the local Chinese and the jungle troops (guerillas) to whom I a couple of times could hand over cash through Kiang Yoong. He even gave me a very timely warning and reprimand once I let out to a Eurasian friend that I had given money to the guerilla fighters. I took very good notice of his reprimand.

Removed from Batu Arang as an enemy subject. One day straight after work Ukawa came up to my bungalow just as Boy carried in my meagre meal. Ukawa told me that the Japanese military authorities had demanded that I, as an enemy subject, should be removed from Batu Arang and that he in three days would take me down to Kuala Lumpur. "You are allowed to take your money with you and a small suitcase or box and how much money do you have?" asked Mr. Ukawa. "Not very much," I said, "a couple of hundred dollars perhaps," This brought Ukawa into a sudden and terrible rage. "Your Boy must have stolen your money," he said and he turned round, grabbed Boy, and started beating him up, while his rage increased. I had had enough by then and with my very best voice of command I looked him angrily right in the eyes and called out: "Ukawa San!" His arms dropped limply down and with open mouth he stared at me with eyes full of surprise. I gave Boy a small side-ways nod and he quickly disappeared. Ukawa turned round and left me and I wondered what kind of thoughts then was in his mind. 126 Very soon after Ukawa had left, Kishi came up and told me the same story about the end of my stay in Batu Arang. "What more do you know?" I asked him. "I do not exactly know what sending away means." "Ah, Ah, mati tida, mati tida." (Ah, Ah, not to die, not to die), he assured me. He maintained - and in a way I think he believed it - that the Japanese soldiers looked after their prisoners; but how wrong he was. Later in the evening quite a few of my friends were calling to wish me well and they thanked me for looking after them and helping them to earn money for a living. One of them, Supaiah, a nice, small Tamil with a big warrior beard, asked if he could get my drinking bottle, a bottle I used to bring with me full of drinking water every morning. "What do you want that for, Supaiah?" I asked. "Ah, Tuan punya bottle." (Ah, my Master's bottle) was the touching reply. The last ones to visit me that evening were Apanah and Mathaven, who, in common with Doctor Dasen, had the welfare of the village population first of all on their minds. Among other things, Mathaven had repaired and re-installed the Batu Arang water system, a feat which made him loved by everybody.

Saying goodbye

Back to my last full day in Batu Arang. - After I had distributed the above items I went back to the bungalow; I had a few more well-wishers and farewell visitors and then I took a last stroll over to the hill behind the wood distillation to observe the lovely sunset there just once more. I got up fairly early next morning, sitting ready for further instructions from Ukawa. He soon arrived and asked me to come down and take a final farewell with my staff and workers. When I came down I saw he had lined them all up in 128 two rows; he put me in the middle of the front line with himself on my right side and Kishi on my left. Then Ukawa wished me good luck (all humbug I soon found out) and he turned towards me with a deep bow, and so did Kishi. I answered by thanking all my workers and wishing them good luck. "You know the Japanese will look after me," I said, "and be careful all of you." I did not turn towards either of my two "guardians"". I wanted to show these two men that I did not want any sentimental play - but it was really sad to leave all my nice and loyal people behind to an uncertain fate.

.jpg)

.jpg)

The Plywood Factory. 1931 to 1942

Although Thiel Marstrand says the Batu Arang plywood factory began in 1932, it had earlier beginnings.

The Malayan Matches' factory had closed down on 30 September 1926, and most of the machinery had been sold off by the receivers. Its last manager was Mr. F. Mudispacher. The obituary of Mr. F. Mudispacher in The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser of 25 February 1928, reported: " The funeral took place at Cheras yesterday evening of Mr. F. Mudispacher, a Swiss subject, manager of Malayan Plywood Veneers Limited at Batu Arang.... deceased... was formerly manager of Malayan Matches and assumed management of the Plywood Company on its inception in March last."

Plywood manufacture, although not as far as we know, by J. A. Russell was planned in 1927. The F.M.S. Secretary's Forestry report for 1927 included: " A new industry, namely the manufacture of veneers and plywood, was started at a factory at Rantau Panjang on the site formerly occupied by Malayan Matches Ltd. The company expected to start producing early in 1928." (The Straits Times , 9 July 1928.) A notice in the Straits Times of May 1928 reports that a Mr P. Hoffner, who had been manager of a rubber estate had joined the Plywood Co. at Batu Arang. However the Company went into Voluntary liquidation in July 1928 and was offered for sale in sealed offers by October 15, 1928. Archie Russell during his speech at the 17th A.G.M. of Malayan Collieries 31 March 1931, said: "During 1928, we purchased the land, buildings and plant of Malayan Veneers and Plywood Co., Ltd (in liquidation) adjoining our Batu Arang property."

Archie spent four years from 1929 researching the timber industry. As he wrote for his speech at the 1933 A.G.M. of Malayan Collieries: "my firm in its private capacity has during the past four years very carefully investigated every phase of the business, from logging to final utilization by the purchaser of the timber, and the whole of the results of this outlay in time and capital has been placed at the disposal of your company." The Chief Secretary of the F.M.S. in his report published in July 1929 commented that: " It is regrettable that both the plywood and wood distillation industries, which were taken up by private enterprise, failed." (Straits Times 15 July 1929.p5). However 3 years later Malayan Collieries had succeeded.

1935 The report of the company said: "Plywood Department.- The production of the works amounted to slightly over 6,000,000 sq. ft. of plywood. The bulk of this was sold in the form of rubber chests, the demand for which in the latter part of the year was in excess of capacity. The local demand for plywood in sheets is increasing and this branch of the business will be developed. Timber- The pilot sawmill was erected and put into satisfactory commission. In addition to producing the sawn requirements of the property several parcels of lumber were prepared for trail shipment to London. Railway lines into timber areas have been extended in order to ensure ample supplies for all requirements." The Straits Times, 23 March 1935, Page 9

At the A.G.M. in March H.H. Robbins said:“The Plywood Department operated full time throughout, but unfortunately, and primarily owing to our anxiety to meet customers in their requirements to cope with the heavy shipments of rubber just prior to the enforcement of restriction, our stock at the works were depleted and with heavy orders on hand it was not possible to build them up again until the end of the year. During that time our deliveries were irregular and to those who were inconvenienced in this way I would add, to the apologies already conveyed by the general managers, the regrets of the board, who offer every assurance that with the capacity of the works accurately gauged, deliveries in the future can and will be punctually made. The wood distillation department showed a satisfactory return both technically and economically and indications are that during the current year the demand for its products will be such as to keep it fully employed. Work in connection with the timber business was confined to the operation of the pilot sawmill, the completion of a check-survey of the area applied for- resulting in a revision of the original boundaries- and a further extension of the railway into our existing areas, which extension will also serve the larger area. The negotiations referred to when last addressing you are not yet concluded owing principally to the delay caused by survey revisions”. The Straits Times, 1 April 1935, Page 11

From the 1937 Director’s report: “ The production of the plywood works was fully five million square feet of plywood, the bulk of which was converted into rubber chests. The demand for plywood board improved, and the packers grade rubber chest became more popular. The pilot sawmill continued to meet the main requirements of the property and one or two parcels of lumber were sent to the Home market. The construction of the railway to the timber area continued. The wood distillation plant continued in operation throughout most of the year, occasional short stoppages being made in retorting to enable stocks to clear. Progress in marketing the products is still slow, although the position is improving.”

The Straits Times, 25 March 1937, Page 7

The A.G.M. held on Tuesday March 30 was concerned with the recent strike at the Colliery where one of the strikers was killed and thirty three arrested. The mill was not affected and Thiel spent many hours as a volunteer at the bottom of the East Mine in the dark guarding the motors and pumps. The Government sent a company of the Malay Regiment out to Batu Arang, where they marched through the village in a show of strength, and the miners went back at work .

1939 AGM. “The plywood section had a satisfactory year," Mr. Robbins said at the A.G.M, "and at last they had overcome the conservatism which for so long had resisted their sales endeavour.... This does not apply to such as wood preservative and while our “ MalAsote” is really a first class article, it is just characteristic of the regard in which local products are held, that it cannot be sold in anything like the quantities which the market could absorb. Progress though slow, is, we feel, sure, and I hope it will not be long before “MalAsote” in its sphere is held in the regard that “MalAply” now enjoys.”

The Straits Times, 1 April 1939, Page 7

From the 1941 Directors's Report of Malayan Collieries:“The subsidiary undertakings operated satisfactorily, according to the demand for the products. The capacity of the plywood factory was almost doubled and the quantity sold was fully twice that of the previous year. Toward the end of the year, the very large emergency demand for timber within the country had started to tell upon the regularity of the supply to the plywood factory.” The Straits Times, 21 March 1941, Page 4

From the AGM: “ With the shutting off of all supplies of plywood chests from Baltic sources, the demand upon our plant represented almost the full requirements of the Malayan rubber industry. Further plant was purchased and installed and every effort has been, and is being exerted to expand production to meet demand. As mentioned in the general managers’ report, the competition for forest labour set up by the emergency timber requirements of the governments have temporarily reduced our supplies of timber, but production is now well up on the grade” The Straits Times, 29 March 1941, Page 4

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Plywood Chests and Types of Timber