For the descendents of Richard Dearie and his son John Russell

My father inherited East Grove house in Lymington in 1969, at about the same time that the Berthon yard constructed their marina and moved Maya into it. Since the longest berth was 40 feet (12.1 metres) and Maya was 43 feet (13 metres) long, with a shallow forefoot that caused her head to blow off in a wind, getting into or out of the marina was tricky. He therefore decided in 1971 to sell Maya and concentrate on the house and garden; he had never had one before, as we had lived in a flat in London. However he did not live to enjoy them long, as he died in 1973. Meanwhile the two families who had bought her were sailing Maya out to New Zealand via the Caribbean; a friend of a friend sighted her in Martinique and told me. It was good to know that she was safe.

John Dennis Russell

Born 14.3.1911 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Died – 19.1.1973

Chartered Accountant and Commander in R.N.V.R.

John Dennis Russell by his daughter Georgina Craufurd.

Written for the new owners of his yacht Maya.

With his mother Madeleine at Whitley Bay, Northumberland.

Four generations: John with his mother Madeleine Russell nee Mossop, centre, and her mother May Mossop nee Fox, left, and May's mother Annie Fox nee Dearie right.

With his Aunt Theo.

At Malvern College in 1927. Second row from the back, third from the right.

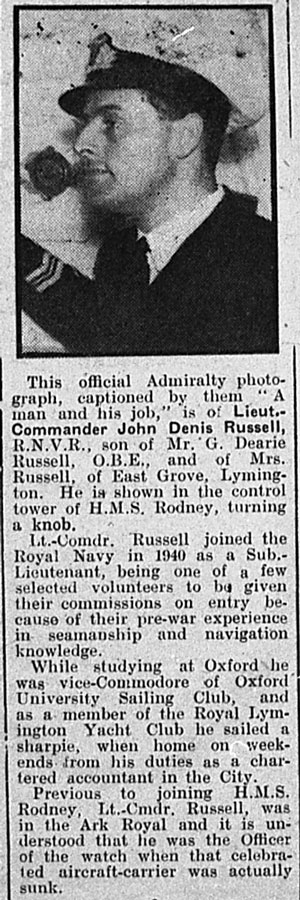

Taken by a Picture Post photographer .

August 28th 1943. Much derision was ascribed to the article writer from the family for " turning a knob" as a description for the commander of H.M.S. Rodney.

Helen Russell.

John with his mother Madeleine in Kuala Lumpur. The family returned to the UK soon after his birth.

With his cousins in 1922 at the age of 11.

At a fancy dress party dressed as a yacht.

He was still in the Navy after the war had finished when he met my mother, who also lived in Lymington. (They had not however met before this.) They married soon after he was demobilised, in June 1946. My grandfather George gave them his 36 ft. 9” Gauntlet yacht Lentune (which he had had designed and built in 1937 by H.G.May of the Berthon Boat Co. to replace Joyce) as a wedding present; he did however come with the happy couple on their sailing honeymoon, as my mother had never really sailed before! (Lentune is an old name for Lymington.)

Taking the salute on the Ark Royal.

Education.

John Dennis Russell was educated at Malvern College, Worcestershire and then at University College, London, where he read Law. During this latter period his parents were waiting for the right house to come on the market in Lymington, and were living in their WWI Harbour Defence Motor Launch (built in 1917) which had been converted into an 80 ft yacht named Joyce. This was normally moored half-way down the Lymington river, but during the family’s summer holiday they would go down to the West Country or over to France. (In fact, while John was at Oxford he had appendicitis and the Master of his college could not contact his parents, because of where they were living; so the Master had to act in loco parentis and give his agreement to operate.) During John’s ‘gap term’ between school and university, he learned watercolour painting from a noted local artist, Maude Speed, and went to the School of Navigation for fishermen at Southampton. But he also had a natural aptitude for the sea; he and my grandmother swept the board one summer in ‘X’ class keelboats, with my father as tactician, and he also made a detailed chart of the waterways that used to run inside the marshes on either side of the Lymington river. In this, I believe that he was inspired by Erskine Childers’ book The Riddle of the Sands (1903), of which he had a copy.

After John had got his degree in Law at University College, Oxford in 1932, he was soon called to the Bar at the Middle Temple, London. (He had been doing the two courses simultaneously, which involved eating his official dinners at the Middle Temple before late-night drives back to Oxford.) He did not however go into chambers, but regarded this qualification as an advantage in his chosen profession of Chartered Accountancy, for which he then trained at Binder Hamlyn & Co. (He finally rose to be Senior Partner at the time of his death.) But he continued to sail smaller craft; he raced National 12s and (more challengingly) International 14s at Oxford (for which he got a Blue) and during vacations, and (later) International Sailing Canoes at weekends during the 1930s. He was friends with Stuart Morris (who had sailed for Cambridge) and with Uffa Fox, who designed a winning International Canoe for him named Wanderer in 1932. He sailed Wanderer most successfully during the next three years. (I think she may have been a graduation present from his parents.) All these yachts and dinghies are commemorated by wooden half-models which my father made to scale; they bear details of dates and measurements on engraved plaques. This was the generation which became interested in the Bermudan rig and the mechanics of flight, and applied these ideas to sail design; in fact, my father’s interest may have been aroused by a book which he won as a prize at school called The Beauty of Flight.

When the Second World War broke out, John Russell volunteered for service in the Royal Navy, but was not needed for the first six months; instead he was sent into the Thames River Police; I gather that he had never been so bored before or since! (It was the period of the Phoney War.) When he was finally called up, after training he was transferred to the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal which cruised in the Mediterranean protecting convoys to Malta. He was in her when she was torpedoed on 13th November 1941, and was one of the skeleton crew left on board during the attempted tow towards Gibraltar; the crew had to let themselves down the flight deck on ropes in order to be taken off, since the ship was listing so badly by then. They were taken to Gibraltar and he made his way back to England in the fast minelayer Manxman. He then went into HMS Rodney and served on the Arctic run to Murmansk during the summer after Russia was in the War on our side. It was obviously a dangerous time, but luckily the Germans had not yet realised that Arctic summer days were 24 hours long; my father told us that after ‘normal’ day’s end the German aircraft would go back to base, and my father would look for wonderful wild flowers during the short summer. It was at some point when my father was in Rodney that he performed an act of quiet heroism. The ship’s big guns were supplied with ammunition via a hoist like a lift-shaft from the lower deck; one day some ammunition got stuck in the hoist, so he took off his jacket, climbed down and freed the ammunition. This action only came to light after my parents were married; my mother found the suede under-jacket that my father had been wearing at the time and which had got covered in grease. She took it to the cleaners, where it was recognised by the boyfriend of one of the assistants, who told my mother the story. Later on, around 1943, he was drafted into the team which planned the invasion of France on D-Day. It is my belief that he may well have been the originator of the idea, inspired again by The Riddle of the Sands; if you turn the idea of Germany invading England on its head, you get the idea of England preparing an invasion using similar creeks and harbours on the south coast of England like Lymington, Beaulieu, and Poole Harbour. After the invasion was underway I think he went back to Rodney at Scapa Flow in 1944 for a while, as he told us how he learned to play golf there; it was not entirely successful, as whichever way he hit the ball, it went into the sea! Then he was sent to the Admiralty in London; this was the period of the V1 and V2 rockets, and he had to sleep in a duty flat in Admiralty Arch; so life was fairly exciting.

I was born in 1947, and went sailing from the age of two years. When however my younger brother was born, my father felt that Lentune was a bit small, so she was sold and my father bought Maybird in 1950. At the time she was called Maya, and this was the name by which she was known for the next thirty years. He gave up racing, as he said it was no good if you had a family, and took to cruising; his knowledge of navigation stood him in good stead, though we did tend to keep to the deep water channels! My father altered her rig to Bermudan, because the first time that he tried to hoist the gaff, it was an even chance whether he or the gaff went up the mast! His great interest in aerodynamics, mentioned above, also influence him as he felt that the rig was much more efficient. He made a few other alterations at the time, putting on phosphor bronze cleats, a ‘bits’ in place of the Samson Post, and a proper chain, anchors and winch. He also exchanged the positions of the galley and the for’ard ‘heads’ (toilet), as it was my mother who would be spending a lot of time in the galley. (The for’ard folding washbasin was made of aluminium and came from a Wellington bomber.) Soon after, he replaced the old Kelvin engine with a Coventry Climax engine, of the sort which normally powered fork lift trucks! (He was given it as a thank you for advising the company on financial matters.) He had found by experience that the old engine was not powerful enough to get our yacht and someone else’s out of trouble. My brother first went sailing in her at the age of three months, and is the toddler in the Bekin photograph, taken in the summer of 1950. (I am the young child.) Every available summer weekend and holiday time we went sailing, and in winter we would come and see the yacht in the Berthon yard in Lymington, where she was out of the water in a shed. Before my brother and I went to school, we spent all summer living on Maya in a mud berth in the yard; it was the time of the terrible smogs in London, where we lived, and my parents were worried about the effects on young lungs. Even after this, we would live in the yacht in the yard over the summer holidays; my father would come down at weekends from London by train, and during his holiday we would sail down to the west country or over to Cherbourg, the Channel Islands or Brittany. Later, when we had a sailing dinghy, we would tow the dinghy astern of Maya to Poole Harbour or Chichester harbour and use Maya as a houseboat; meanwhile we would explore all the creeks in the dinghy. Around 1965 he made various alterations to Maya’s interior. He designed a separate fore cabin, with adjacent ‘heads’ and basin, separated by a folding door, in the fore peak for my brother and myself in place of the pipe cots, and he had locker doors made in front of the shelves above the saloon bunks which folded away. He also put in a more powerful marine engine, a Parsons Pike. Maya became a wonderful floating base for Cowes Week during the time that my father was Rear Commodore of the Royal Yacht Squadron. (He had been elected a member soon after the War, and was on the Committee of Management for many years.) I remember how Christopher and I had to dress the yacht overall with International code flags one morning by ourselves, knowing that my father was watching from the Squadron, where he and my mother had stayed the night before. He had arranged everything ready, but we could still have easily made a mess of it.

From his obituary :"...called to the Bar in 1932 but choose accountancy as career. Served his articles with Binder, Hamlyn and Co and was admitted into partnership with firm in 1948 becoming a senior partner on Jan 1 1972. He was a member of the council of of the Institute of Chartered Accountants for many years and at the time of his death was chairman of the Investigation Committee. He was always ready to accept additional responsibilities, and his legal training and his faculty for precision in drafting and discussion made him a valuable member of a number of government committees. He served for a number of years on the commission for the new towns and was a member of the Inland Board of Referees."