For the descendents of Richard Dearie and his son John Russell

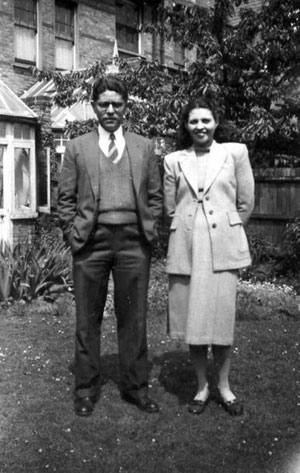

Victor Davidson Born Edward Russell in about 1907 in Kuala Lumpur.

Died 3 May 2005 in Australia

Engineer.

An account of his life written by himself.

I asked the girl I was engaged to, that I would only marry if I passed my examination. Her prayers and mine were answered and we borrowed a car from a Chinese building contractor in Taiping, where I was working as a technical assistant in the Public Works Department.

We went to Penang for our honeymoon. We called on Mr. F. G. Coales who was the senior executive engineer of Penang, to inform him that I was now an Associate Member of the Institution of Structural Engineers.

After one week in Penang, we returned to Taipeng. I informed the senior executive engineer of the state of Perak of my recent membership. His advice was that I should apply for a post in the Singapore municipality.

While waiting to decide my future, my wife gave birth to a baby girl. We gave her the name of Helen.

This is my life. Because of my mother’s circumstances, I lived most of the time as a foster child. My first experience was with an old woman in a house in Welds Road in Kuala Lumpur in the state of Selangor of the Federated Malay States before independence. I lived there as a baby to an age of about four years, when I was able to go to school. I travelled with a young girl in a rickshaw all the way to a Methodist school in Damansara Road. It took, as well as I am able to remember, almost half to three quarters of an hour. The school took only girls but also boys as boarders up to the age of ten to twelve years.

While still in the Methodist school my mother moved me to a Chinese family as a boarder, within walking distance. However, crossing a bridge on one occasion, the river overflowed its banks and the bridge was impassible, the Chinese came to my assistance as we waded across.

My next stay as a boarder was with a Malay rubber tapper family and I had to travel by train to a government school in the township of Klang. The school was quite some walking distance from the Klang railway station.

One day instead of going to Klang I went, on the train, to Kuala Lumpur. I walked to Welds Road to visit all the old folks that I lived with in old days. On return, some how I managed to pass the ticket checker at the station entrance door. I got on the train that was going to Klang and I got off at the rubber estate station.

My next home was to Klang itself where my mother had rented a house. I had to walk to the same government school I went when living in the rubber estate with the Malay family.

She gave me one cent for lunch money with which I could buy only preserved fruit. Consequently, I lost a lot of weight. Seeing my physical condition my mother bought cow’s milk for me to drink daily. On my way home from school I stole my way into a Chinese theatre.

Not long after, my mother moved to Kuala Lumpur, Bukit Bintang Road where she rented a room in one of the row of shophouses. She again gave me one cent pocket money for lunch. To get to school I had to walk through a rubber estate belonging to a Ceylonese family named “Labrooy”. The estate led me to Welds Road, on to the main road, through the forest, crossing a cemetery on to the St. John’s Institution playground. I had to cover the same area on my way home.

Of course, while living in a room with my mother there was a lack of convenience to do any studying. As a consequence I had a caning from the teacher who was a “brother of the order of de la Salle”.

As a consequence I ran away from school and returned home in the evening.

The teacher reported my absence to my mother. I received a severe caning.

On the advice of her friend she and I travelled by train all night to Singapore. On arriving in Singapore she told the rickshaw puller to go to the reformatory school run by the government. At the reform school she went alone to see the officer – in – charge. Apparently she was told that because her son did not have a police report he could not be admitted. My mother told the rickshaw puller to call on any Siamese woman who was accepting boarders. On arrival she left me to return to Kuala Lumpur by train later.

The Siamese woman lived with her two daughters in one of a row of houses on Braspasser Road not far from the seafront where the “Raffles hotel” is located now.

I was given a bicycle whose front wheel was uncontrollable so that I fell off the bike when the wheel jammed in the tram rails.

I attended a school run by American missionaries on a shoe string because three grades were taught in one class by one teacher. I attended that school for six weeks.

The Siamese woman I stayed with had two daughters. The elder daughter was kept by a wealthy Chinese who visited her regularly. After a short time he stopped coming and instead stopped a short distance from the house and sent the rickshaw puller to deliver the monthly allowance. I was asked to follow the rickshaw puller. There he was, the Chinese man in the rickshaw. On my return I reported this to the Siamese lady but was disbelieved by the daughter. She later committed suicide.

The daughter did not want me to live with them. My mother came to collect me and we returned to a house she rented in Ceylon Lane in Kuala Lumpur.

After a few days, I went to live with a Mr. & Mrs. David Freeman. As my foster parents, David Freeman was a lawyer who will play a significant part in my life.

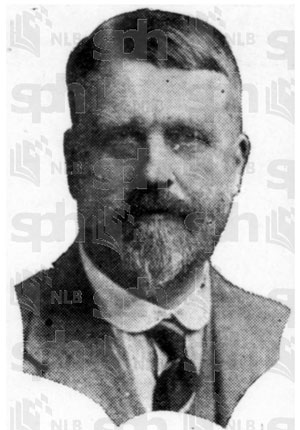

I was told Freeman approached J.A. Russell to adopt me. Refused but agreed to pay for my education. So J.A. paid my school fees at St. John institution, located at Bukit Nanas. My name then was Edward Russell

However, when the Freemans went to England on leave, J. A. Russell wrote to the principal of the school that his brother, George Russell, who was my father, denied he was my father, which of course was a lie, and wanted my name changed otherwise he would stop the payment of the school fees. I did not know what was going on and the brothers at St. John’s wanted me to stay on. In the fashion of a lottery, I picked the name “Davidson” from a number of names that had been written on pieces of paper by the brothers.

On return from leave Ma Freeman asked why I did not take the name of Freeman instead. The Freemans had made it a principle to either adopt the children whose parents wished to disown them, or to send them to the “Barnardo” home in England.

The convent run by the nuns at St. Johns Hill would accept babies whose fathers were likely to disown them and would accept babies of any nationality for a small monthly fee. So the convent had children of the names Munro, Gale, Blight. As the boys grew older they were sent to the boarding school of St. Johns Institution. The nuns had favourites, for instance a “Daisy Shaw” had a qualified electrical engineer chosen to be her husband. Lots of Chinese left their unwanted babies at the convent doorsteps. The babies are baptised and when grown up become servants for school performing cleaning and other duties.

After my name change, I was baptised by a Father Lynch from Australia. My god-father was the parish priest, Father Victor Renard and so I took the name “Victor” as my first name.

After returning from Singapore, I became a boarder at St. John’s and took to studying very seriously. I am grateful to my teacher “Teck Soo”, through his help I received double promotion from the sixth standard to the junior class.

Although I got six ‘cuts’ with the cane from “Brother Dionysius” for rudeness I was first in the final Cambridge University examination and won a scholarship prize of forty dollars.

I went on to the senior Cambridge class. I failed, because instead of studying, I was enjoying the circus with my junior scholarship money of forty dollars. This was a blessing in disguise. The second year I passed reasonably well. I decided to make a third attempt taking more subjects. I had very good marks in mathematics.

Freeman and the school principal believed that I was too young to go to work so it was decided that I should go to the “St. Xavier School” in Penang as a boarder. I took more advanced pure mathematics, natural history and French. I represented the school in soccer and cricket.

Even before I got the examination result I was sent to “Taipeng” catholic school to become a teacher, however, I failed miserably at this profession and went to live with the Freemans who had just returned from leave. In hindsight, if I had contacted the Simpsons (Pa Simpson was the head prison warden, Taipeng prison), they would have adopted me and I would be “Edward Simpson”!

I failed to join the Singapore police force and because there was no guarantee that I would be sent to “Derudoon” Forest College in India, I refused the appointment.

Thus I would apply for an apprenticeship with the Public Works Department. Fortunately a Malay boy resigned to join the Forest Department. My application was accepted and I had to get someone to sign the “indemnity”. Here again I was lucky to have David Freeman accept the responsibility and sign the indemnity.

All approved apprentices had to attend a technical school.

The apprentices were paid forty dollars a month.

Ma Freeman bought a bicycle and I cycled from home to the school five days a week. She was to keep the forty dollars!

Not long after I left the Freemans to live with my mother in Parry Lane in a row of houses in a Chinese women monks’ area. While there, I happened to find in a box belonging to my mother, a letter from my father, George Russell, on which was written “Ruther Glen, Glasgow, Scotland”, together with a photo of a group dressed in Chinese costume among which was a chap named “Jackson” who used to go shooting in a tin mine in “Sungei Besee”, not far south of Kuala Lumpur.

The principal of the technical school was Francis George Coales, my knowledge of mathematics that I picked up in my year in St. Xavier’s school in Penang was an advantage in the studies at the technical school. Coales had a class on advanced theory of structures, I received the top marks and was presented with a book prize. In the final year I was top of the class with 95 per cent. My drawing was good enough to be selected for work in the chief architect’s office.

I was a favourite of the chief architect. Instead of studying under a junior architect I was put to the task of designing reinforced concrete beams for an architectural building designed by the chief architect in the capital of the state of Pahang named Kuala Lipis.

At the same time I made a closer study of the French subject in preparation of the London university matriculation and had to travel to Singapore to sit for the examination. Besides French, there were also four mathematical subjects.

On receipt of a successful result, I approached Mr. F. G. Coales, who was a member of the Institution of Structural Engineers of the United Kingdom, to ask him to recommend me for membership. I got a reply that unless there were at least seven applicants sitting for the examination, it could not be held. I replied that I was prepared to pay the fees of seven applicants. My persistence brought a change of attitude. The institution had a licentiate member who was prepared to supervise the examination, probably for a fee.

The examination was for the graduateship as well as for the associate membership. In the latter there was a design of structures question. The result came that I had passed the graduateship and received a certificate for this, but failed in the practical design. I failed again in my second attempt. In my third attempt, I had a hunch. I was to design a reinforced concrete aeroplane hangar.

After about three weeks, to my surprise I was informed that I was appointed as technical assistant to the building inspector, Kuala Lumpur Sanitary Board.

Apparently there was an Indian in the Public Works Department who had reached the top of his grade and his name was put forward for the appointment as technical assistant to the building inspector sanitary board.

By this time Mr. F. G. Coales became the state engineer of the state of Selangor. He recommended me for the job and wrote a glowing report of my achievements at the technical school, stating that I was a qualified chartered structural engineer and an associate member of the institution of structural engineers.

Before leaving for Kuala Lumpur, Helen was born in Taipeng.

My wife’s grandmother, Mrs. McClelland, travelled to Kuala Lumpur. We had a rented house in Parry Road. Deric, our eldest son, was born in that house. The midwife said that we may advise of his birth to Suffolk House United Kingdom. However, we did not act on her advice. Meanwhile, my mother came to stay with us. She had been advised to come to Kuala Lumpur for an operation for cancer in the womb. This situation seemed to upset my wife’s grandmother and she urged her grand-daughter to return to Ipoh. Meanwhile, my mother left the house to live in house down the road. My wife “Lil” did not follow her grandmother’s advice. Mother had her operation at the Hilltop hospital. The operation was a success. She returned to “Puhket” to live to the age of eighty years. She died when I was sixty years old.

Nelly and Pauline Bligh, two of my step-sisters, went to “Puhket” to visit her. She was living on her rubber estate. She saved all the monthly money she got from the local bank until James Bligh Orr, Nellie and Pauline’s father, died. She built a small house, and bought herself a coffin. She also had a tombstone which was to be erected over her grave. The stone was inscribed the names of all her children. We do not know whether the grave still exists with the development of Puhket as a seaside resort.

While I was living in the rented house in Parry Road I bought a piece of land in a subdivision off Bukit BinTang road. It was semi-detached house. We lived on one side and rented the other side.

I also bought a rubber estate. It was about twenty acres. The former owner a Chinese man, dug holes about ten to twenty feet deep to find gold and there was a small hut to house the rubber that had been through the hand roller. The estate was located about ten minutes walk from the main road from Kuala Lumpur to Seramban. There was not much rubber tapping. The income was selling the rubber coupons and the rubber tapper took his share of the transaction. Sometimes I would be away from the estate and he would put in an appearance at my office as a reminder to go to the estate to carry out the usual transaction. However, the investment was not paying, so I sold the estate at a loss. I was running out of money to complete the construction of the house, so I borrowed two thousand dollars from Lily’s father-in law, Mr. Pierre Martin.

On completion of the construction of the house, Madame Adele, the principal of the convent allowed Nelly and Pauline to come and live with us. My second daughter, Ursula, was born in that house. For some reason or other I decided to sell the house and move to a government house in Jalan Delima.

My daughter Elizabeth was born in that house and Nelly was married to Claude Labrooy and our daughter Helen was the flower girl.

C. O. Jennings went on leave and Mr. Gourlay appointed me acting building inspector. So a telephone was installed in the Jalan Delima house. Meanwhile I paid Mr. Martin the two thousand dollars I owed him on receipt on completion of the sale. In the meantime I contacted a Mr. H. H. Robbins, he was the chief executive officer in the office of J. A. Russell & Coy. Actually, I wrote to Mr. J. A. Russell asking for financial assistance for a further engineering degree in Loughbourough College in England. He asked Mr. H. H. Robbins to interview me. Robbins asked me to meet him at his house. It was not until ten o’clock at night that he arrived home. He asked me which engineering I would be doing. I told him, civil engineering. As an after thought I should have said mining engineering because I would have been more useful to the company of J. A. Russell in “Batu Arang” about 30 miles north of Kuala Lumpur. In fact, my father, George Russell, was a qualified civil engineer. After a short while I rang H. H. Robbins, the answer I got was in the negative. Not long after J. A. Russell passed away while still a young man. As for H. H. Robbins, he died as prisoner on the construction of the Siam railway.

On return of Jennings from leave, Mr. Gourlay appointed me acting town superintendent. On return of the appointed officer I resumed my appointed job of technical assistant.

Then came the World War 2 and the subsequent invasion of Malaya by the Japanese army. C.O. Jennings joined the army as a second lieutenant. Mr. Gourlay appointed me acting building inspector.

Because of incendiary bombs used by the Japs, the wooden plank ceiling was removed. I instructed the contractor to move the planks to another contractor’s property on the road to the hot springs not far from Mr. Pierre Martin’s house on Ampang Road. For fear of the incendiary bombs, the Sanitary Board Office as a whole moved to the house where Mr. David Freeman lived before he sold it for conversion to the Chinese temple. Incidentally, my office was in the bedroom I used to occupy. I used the ceiling planks to build a hut and moved all my belongings from the Jalan Delima house to the hut, but left a box containing my private diary and a photo of my father and his compatriots dressed in Chinese costumes in the house. I do not know what finally happened to the box when the house was reoccupied. When the Japanese war machine landed on the north east coast of the peninsular Lil’s sister Marie and youngest brother Herbert came to the house in Jalan Delima. Pauline moved to live with her sister Nelly who was now Mrs. Claude Labrooy. Of course, Marie and Herbert came to live in the hut. When the Japanese army reached the township of “Batu Arang”, I decided to leave the country. I approached Mr. Gourlay for permission to leave for Singapore. I had to promise him that as soon as my family left Singapore, which they did on the S. S. Hong Keng a 650 ton ship, I would return to my duties in Kuala Lumpur.

Early the next morning we left Kuala Lumpur in my Austin Minor car with our four children, Marie and Herbert, and bags of clothes strung to the roof of the car. It was getting late in the evening we stopped at a rest house for the night. Next morning, we started our southward journey. After some distance we had a puncture in one wheel. A motor cycle stopped and the wheel was pumped up. The rider of the motor cycle happened to be an Australian soldier.

It was getting late and dark so I decided to stop for the night at the Kenieson factory. A few minutes later there was a knock at the door. On opening the door, there stood an army officer of the allies. When Mr. Kenieson appeared, the army officer left. Apparently he thought we were a Japanese fifth column.

While at the Keneison’s I informed them that they should leave the country. Early the next morning, we left for Singapore. After travelling a short distance a chap we happened to know named Arthur Ford stopped us and offered to relieve the load on our baby Austin. He took Marie and Herbert in his car.

At the entrance of the causeway that links Singapore to the Malay peninsular, I showed my passport. We travelled southward until we reached Braspasa Road which was familiar to me because I lived in this area years before. I left the family, Marie and Herbert temporarily at a Chinese hotel.

I went to Robinson Road to find an Indian travel agent whom I had met many years ago. This occurred while I was living in my own house and I went to Singapore for a holiday with a Mr. Colomb. Fortunately the Indian travel agent, Joseph, was in his office. I told him I wanted a passage for my family to leave the country. He said an S.S. Hong Keng was leaving for Bombay the following morning. I returned to the Chinese hotel and brought the family to Joseph’s office where they slept the night before boarding the ship the following morning.

Because I promised Mr. Gourlay that I would return to Kuala Lumpur, I could not travel to Bombay with them.

I stayed with Joseph at his office. The next morning I travelled alone in my Austin Minor, northward, out of Singapore. I drove all day through the state of Johore until I reached the border of the state of Negri Sembilan. I was near the state capital called, “Seramban”. I saw a car off the road in a ditch with a man, who looked European, seated in the car with his throat cut and lifeless. I decided I would go no further. I reversed and returned to Singapore. I could not keep the promise to return to Kuala Lumpur.

Ironically, in Singapore, I met Mr. Gourlay at the Seaview hotel. I told him that my family had left and was in Bombay, India. He must have thought that I would not be able to leave Singapore so he wrote two letters, the first to the Singapore municipality and the other, to the Singapore country board. I went to see the chairman of the latter. He did nothing but introduce me to his building inspector. I got no recognition or promise of a payment for a job.

Meanwhile, my objective was to leave the country. I stayed with Joseph and handed him the money for the passage. I had some money in the Hongkong & Shanghai bank the rest of my money I had transferred to India as a deposit in the Indian bank. I did not get even any interest on the deposit.

Because my family was in India, I approached the authorities for permission to go to India. The reply I received was to write to the Indian government. I thought that by the time I got a favourable reply, the war situation would have changed considerably.

Joseph suggested that I approach the Ceylon government. I took his advice and the result was favourable. I could go to Ceylon if I had permission to leave the country.

Well, I wondered, whom shall I approach? I thought my best bet was to see Mr. Francis George Coales who was now the director of public works. He wrote a glowing account of my career, saying that I would be useful to a future government. This letter, Joseph handed to the officer-in-charge and I was to be a passenger on one of the seven East India ships to go to Ceylon from Singapore.

On the appointed date, about the second or third of February, we were told to board the ship. Joseph drove me to the wharf and I left the car to him.

On board I hid myself in my cabin, which I shared with an Indian, until the ship sailed. The ship moved in a zigzag fashion as it sailed to avoid being bombed by the Japanese war planes that were returning from Java. Fortunately, an Australian sloop kept the plane high above the ships. It was getting dark and we passed through the Sunda straits with all the ship’s lights off and the engine in slow motion until all the ships cleared the Sunda straits.

To go to Ceylon, the ships should be heading north, but instead, the ships were going westwards. Apparently the captains of the ships were informed that there were Japanese submarines in the Indian Ocean. The ships then travelled northwards. We were on our way to Bombay where the family was in “Dubanga” flats. Mrs. Brown, an English lady in Bombay who had the responsibility of finding accommodation for refugees, phoned Lil and told her that I was on one of the ships. As there were all sorts of people to be accommodated in “Dubanga” flats, she decided to move us to the flat that housed the polish refugees from the north of India.

Mrs. Brown found me a job with E. D. Sassoon’s & Coy, a Jewish firm in Manchester, United Kingdom. The company had cotton & woolen mills in Shanghai, China but these were overrun by the Japanese.

The company employed me as construction engineer to construct air raid shelters. Their assistant engineer, a Muslim mechanical engineer named “Bimjee” found a flat by the beach in the township of Mahim, on the outskirts of Bombay. The flat was vacant because the German army was at the doorstep of Cairo, Egypt and wealthy Indians were fleeing from the sea coast.

Marie joined the “waifs” and Herbert, together with Helen, Ursula and Deric, continued his education by schooling at the Bombay Scottish Orphanage, Mahim.

I used to walk to the Mahim railway station and travel by train to the station where the workers were transported by the company bus to the woolen mill.

I had my lunch with the mill manager and his family. After a short nap we returned to our respective jobs. At the end of the day, the workers and I mounted the company bus which drove to the railway station to take us from there to Mahim railway station.

We used to go to mass at the church of Our Lady of Victories, Mahim. Because the church was in such a bad state of repair the church committee organised a raffle to raise some money. I bought half of all the tickets and won the prize. I decided to donate my winnings back to the church. In appreciation, they presented me with two pictures, one of the sacred heart of our blessed lady and the other the sacred heart of Jesus with following words:

" To Mr. And Mrs. Davidson and family In appreciation of your generous gift. From The president and members of the Emergency Repairs Committee, Church of Our Lady of Victories. Mahim. 18th.June 1944".

I was transferred back to the head office in Bombay. Meanwhile the Malayan government opened an office in Bombay as well as one in Ceylon.

I got a letter to report to the officer in charge. On arrival I was asked to go the room where there was of group of public works department engineers in Malaya. Not in the group were Mr. F. G. Coales and Mr. Anderson who was the personal assistant to Mr. Coales. He had a chat with me before Mr. Coales was free to see me. Mr. Anderson was the engineer who supervised the construction of the reinforced concrete beams which I had designed while I was in the chief architect office in Kuala Lumpur.

Later I was told that the ship they were on, was about the last to leave Singapore before the surrender, and was sunk by the Japanese navy. As to the circumstances of the death of Mr. Coales and Mr. Anderson, we do not know.

By the way, a Mr. Blackwell, a colonially appointed officer, accused me of being a Japanese spy. In fact, it was found later that he was a Japanese spy! The outcome of this I do not know.

Later on, after the German surrender, I was informed by letter I could retire from the government service, which I promptly did. Subsequently, I was informed that my pension was withheld, probably because I was accused of being a Japanese spy.

I wrote to Mr. David Freeman about the whole situation.

Meanwhile, there was a change of the officer in charge of the office in Bombay. He was a former chairman of the sanitary board in Kuala Lumpur. With a word from Mr. David Freeman, my pension was restored with which I was able to pay for the passage to England.

While in Bombay and the Japanese army was on the Indian border the British sent reinforcement to India. Included in the reinforcement was the air force. Flight Lieutenant James Bligh who came with the air force and was temporarily stationed in Bombay. Funnily he found where we lived and visited us. However his wife complained to the air force Marshall of her illness and wanted her husband to return home. After the war James was employed in the home office.

Lil’s brother George was a civilian prisoner of war in “ Changi “ Singapore.

With the Japanese surrender he came to Bombay and then he went to England. On the advice of his uncle Willie Toft he got a job in the foreign office.

Our son James Ernest was born in Bombay and was baptised in the church of Our Lady of Victory in Mahim, Bombay. He was born in a hospital run by Indians with “ Dr. Pense “ in charge. They put a red dot on his fore head. He has born under the star of the “ elephant garnish” a star of wisdom.

Shivage Park was located opposite our flat and Gandhi was the man who was fighting for the independence and self government of India without violence. One day disembarking from the tram and walking to my flat a group of Gandhi followers approached me and removed my toppy hat and put a white Gandhi cap on my head and handed me back the toppy hat and allowed me to proceed..

I was not recalled to return to service as appointed in the sanitary board in Kuala Lumpur.

I decided that being almost three quarter of the way to England for the sake of the future of the children I should proceed to England. There was a future for me if I returned to Malaya but not for the children because they were not Muslim.

I wrote to George that the family was on board the ship called the “ Stradeden ‘and I was prepared to buy a house to accommodate them when they arrived. However George consulted his uncle Willie Toft who was retired but used to work in the home office. He asked George to go the home office to explain to them the situation. After all the family were evacuees due to the war in a similar situation to those from Hongkong or Shanghai, China. The home office agreed to treat them as such so on arrival in Southampton the home office staff put them on the train for Liverpool (?St.) station. They slept the night in an air raid shelter and travelled to Kidderminster the next morning and then by bus to “ Blaxhall “which used to be a German prisoner war camp.

About two weeks later I resigned from the East India Mills, Bombay and sailed to England. On arrival in London George and I interviewed an officer at the home office who gave the necessary information to travel to Blaxhall and advised me that I was not to stay there permanently.

I approached the institution of structural engineers to put my name forward for employment. Soon after I got a letter from a Mr. Nachshen to come to London for an interview after which he said I got the job.

I moved to London and went to live with George at “ Earls Court “

I got a few days leave. I left the office the usual time to catch the train to Kidderminster. By the time I got to Liverpool Street station the train for Kidderminster had left because it was Christmas time and everyone was leaving for home. I had to take the train to Worcestershire and I took a taxi to Blaxshall, which cost five pounds. And it was nearly midnight..

After a week I returned to London to resume work in Mr. Nahschen’s office as assistant engineer.

During the weekend I travelled all over south London looking for a house to buy. Eventually I went to an estate agent who said there was a semi-detached house in Normanton Road in South Croydon a walking distance from South Croydon railway station. I inspected the house with the agent’s representative, a lady who was also looking for an accommodation for her sister who was divorced from her husband. I agreed to let her have the top floor. The middle was vacant. The bottom floor was occupied by a retired Indian army officer. I let the top or dormer floor to Mrs. Mills, the sister of the agent’s representative. After the transaction of the purchase of the house was completed we moved from Blackball to 29 Normanton Road, South Croydon and occupied the middle floor.

After the first month the Indian army officer vacated and we moved to the ground floor. The middle floor was vacant at the request of the house agent I let the middle floor to a semi-blind man. It was with pity I agreed, not only he and his wife his brother in law and his wife also came to live. On the rather large landing serving also the dormer floor where Mrs. Mills lived with her two children. The semi blind man’s brother in law was making wooden boxes as containers for shop keepers. One night the fire place in the lounge caught fire. The fire brigade had to be called to put the fire out. Not only that they thumped the floor with shoes. They also appealed to the rent tribunal for a reduction of the rent. Of course the appeal was not successful. The rent was only two pounds a month.

The ground floor part of the house had a telephone and had occupiers name in the telephone directory. We had several visitors from Malaya.

Marie and George and Herbert came to live with us and went to work as usual. The girls went to Saint Ann’s College Sanderstead .They walked through a garden patch. On the way home after school they went to a sweet shop to exchange their coupons for the sweets. Deric walked to catch the tram to Purley and walked a short distance uphill to a catholic school. Helen was too old to win a scholarship to public college so went to what was called a combination school. On Sundays we walked through a garden patch to the Roman Catholic Church named Saint Gertrude at 46 Purley Road.

Our youngest son was conceived in 29 Normanton. He was born in a nursing home attended by a doctor and was breast fed until one year old.

Mr. Nachshen’s original office was an old four storey building off Victoria Street next to a catholic church where I attended mass at lunch time. At this I was given the job of designing reinforced concrete tanks for a sewerage system in the East Indies. In fact it was a job from the Danish consulting engineers who have established a consulting practice in the United Kingdom and worldwide.. The name of the firm is “ A. V. Addler “.

Mr. Nachshen moved to an office on the forth floor of the of the row of buildings facing Victoria Street, actually not far from Saint Margaret’s cathedral.

While working in Mr. Nachshen’s office I kept myself up to date with modern structural analysis by attending classes in Westminster College and Battersea College in the evening after work. The subjects I covered were the structural steel code, structural analysis and soil mechanics. Pre-stressed concrete, and water retaining structures

Usually I would be in time to catch the bus to South Croydon and catch another bus to stop at Normanton Road.

Sometimes I had no evening class I would go direct after work to Victoria Station but would miss the train to South Croydon and had to take the train to North Croydon station. This would mean I had to wait to board the bus which stops at South Croydon station before proceeding to its final destination, “Sutton “ then I had to walk home from the station.

Funnily enough, while I was waiting for the South Croydon train I met C. O. Jennings. He came up to me and told me that I would get his job if I returned to Kuala Lumpur, Malaya. My reply was that I intended to stay in England for the sake of the future of my children

While in Malaya before the World War two, I had the desire to send the family to live permanently in Australia and I would maintain them permanently until I retired from the government service and join them in Australia. But this procedure was not to be.

At this stage, Noel was about four years old and Lily did not want to live in England any longer.

I went to Australia house in Fleet Street, London. I was told I would have to live in England for five years. Anyway they sent my application for a job in Australia. Soon I got the offer of two jobs. One from the department of building & construction and the other from the state electricity commission of Victoria as a building supervisor. I chose the latter because I and the family will stay in one place. Incidentally, we sent to “ Keiwa. Bogong.” where underground operation schemes were in progress.

However, if we were to come to Australia under the scheme of British Migrants, as such we have to prove British descent.

I wrote to Glasgow Scotland for my father’s birth certificate. I got a birth certificate which states his name was Joseph Davidson and was a gardener. I presented this certificate and my passport which stated I was British by birth. A few weeks later I received a letter to be ready to travel from London to Glasgow, by train from Liverpool Street railway station.

I have to go back in years. After I moved the family to 29 Normanton Road I thought I would invest some money I had in properties. Not far from the South Croydon township I bought four terrace houses in an auction and in the same auction I bought a 3 storey house fully occupied and producing some rent.

However the next week I received council notice that the terrace houses in the township has to be repaired to the required standard. I refused to carry out the repairs and the houses were re-auctioned and I had to pay the cost, which was a dead loss. However I kept the other house until I was told to be ready to emigrate and sail from Glasgow. So, the rented house in Sutton had to be sold. What should I do? The ground floor was occupied by a Scottish lady and she could not pull on with the English lady who occupied the first floor. The Scot lady had a daughter married to a wealthy South African. I suggested that her daughter should buy the property and give the English woman notice to vacate. She did accordingly and the property was sold in time to get the negotiation through before leaving for Glasgow from Liverpool Street railway station to board the ship for Australia.

We travelled to Glasgow one week earlier before boarding the ship named S. S Cameronia . On arrival in Glasgow we stayed in an hotel. I left the family in the hotel. I boarded a tram to ‘” Rutherglen “ hoping to meet my father. But the book “ The Russells “ recorded that by this time of my attempt to meet him, he was already dead.

I returned to the hotel. The next day we took the Glasgow- Edinburgh train. In Edinburgh we visited the castle and the church at the foot of the hill. While walking along the main street we dropped in a shop that sold tartans. We bought the required number of yards of the “ Davidson “ tartans.

On return to Glasgow we had the tartans made into tartan costumes. We were in the queue that boarded the ship dressed in our tartans. The “ Glasgow Times “ had made a record of our boarding the ship.

We were the largest family in the ship. We were given the privilege of sitting on the same dining table as the captain of the ship.

While on the ship named “ S. S. Cameronia” we made friends with a family from “Glasgow” Scotland named “ McCauley’s ‘ and took a lot of photographs together. The ship stopped in Ceylon harbour. We did not go the capital “Colombo “ but bought two wooden elephants from the stalls on the foreshore.

The ship took almost fifteen days to arrive at “ Freemantle “ harbour. Quite a number of passengers went to “Perth “ by bus. The “McCauley’s “ and ourselves had “ fish & chips “ in “Freemantle “ and boarded the ship for “ Port Melbourne “ . On arrival the family were dressed in their “ tartans “ photos were taken and appeared in the “ Sun “ newspaper. We housed in for the night in a temporary timber shed. The evening in November was still bright, so, we boarded a tram which went to “ St. Kilda” beach then entered the “show grounds “ to try the “ ferris wheel “. It was fairly dark by the time we reached the temporary accommodation.