For the descendents of Richard Dearie and his son John Russell

J. A. Russell and Co. Ltd. 1945-61

1942-45 after the Japanese occupation. Don and Bob Russell fight for Control of the Company.

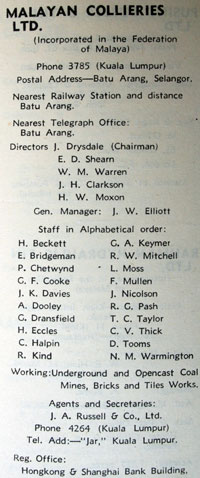

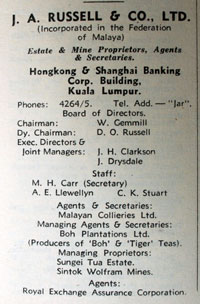

According to Don Russell’s notes the directors of Malayan Collieries Ltd. at the fall of Malaya in 1942 were H. H. Robbins, J. Drysdale, A. M. Delamore. A. J. Kelman, and F. Cunningham. Kathleen Russell’s notes state that Shearn had also been appointed a director just before the evacuation. The last minutes of J. A. Russell and Co. Ltd. for their meeting on 11 November 1941 show that the directors were H.H. Robbins, J. Drysdale. Mr. A.W. Delamore, and Mr. J. H. Clarkson. H.H. Robbins died in 1942, and John Drysdale was interned. A. J. Kelman escaped capture and returned to England. In London the two companies that had worked with the Collieries were Don Russell’s company of W.R. Loxley and Co. (London) who had been the Collieries London Agents. They had equipment for the Collieries that had had to be diverted to Australia as well as exports unsold in England. In 1941 because of disruption to the post in Malaya, Loxley’s had taken on the distribution of Collieries' dividends. Pam Russell, Don’s wife, was appointed a director in 1943. Andrew Beattie who had previously run Loxleys, was a director with one share, but had left Loxley and Co. and started his own company in 1937. However he retained the work of engaging staff and the Collieries paid him an agency fee.

The Malayan Planning Unit in England decided as soon as Malaya had fallen in 1942 that a supply of coal would be essential to support the country’s liberation. They were asked by the War Office to make plans for coal production. A small team was recruited. Bob Russell whose income was derived from the Russell trust fund had retired to Canada by the start of the war. Letters between him and Kathleen show how anxious he was that Russell businesses should be run well. Once Malaya had fallen presumably the trust was no longer able to provide him with an income. He returned to England in 1943 with the intention of getting a job and stayed with his brother George in Lymington.

Beattie and Kelman formed a new board with Bob as secretary. Bob was later made a director, and was sent out to Malaya as managing director. They appointed Elliot as general manager on a salary of £5,000 per year. When Kelman heard that Beattie had been approached by the Planning Unit about the Collieries, he informed Loxley and Co. There were long discussions between Loxleys and Beattie's as to which of the two companies should be the agents for re equipping the Collieries. Loxleys had been the buying agents but Beattie had already done some work and was not willing to hand the buying over to them. Discussions led to a compromise; Loxleys gave Beatties the details of the equipment and cargoes that had been diverted to Australia, so that they could be given to the engineers who were arranging to reopen the mine. Mr. Beattie agreed that any developments would be notified to Loxleys. Beattie had registered his firm as a private company: Andrew Beattie & Co (London) Ltd., in 1943. Malayan Collieries Ltd. had been registered in England on the 30 September 1944 with a business address at 4 Queen Victoria Street, E.C.4. The directors were given as A. J. Kelman, A. Beattie alternate for A. M. Delamore G. M. Dalgety alternate for F. Cunningham R. C. Russell A. M. Delamore F. Cunningham and J. Drysdale.

By 25 April 1944 Loxleys had realised that Andrew Beattie and Bob Russell were undermining the interests of Don Russell who was still interned and wrote an open letter to the board of Malayan Collieries questioning who their London representatives were. The Collieries replied in a letter of 21 September 1944 that Loxleys were no longer their London agents. Bob Russell as secretary of Malayan Collieries wanted Andrew Beattie as the London Agents. In a letter dated 1 November 1944, possibly written by Loxleys they pointed out: “The active members on the reconstituted Board are Mr. Andrew Beattie and Mr. R. C. Russell, the others being just names or unable to act. The two gentlemen mentioned have grudges against Mr. D. O. Russell. Mr. A. Beattie by reason of the fact that he was virtually discharged from W. R. Loxley & Co. (London) Ltd., Mr. R. C. Russell who was a principal of J. A. Russell & Co., to the end of 1937, by reason of the fact that he also was asked to resign."

It appears to be Beatties that then worked with the U.K. Government to organise the dispatch of the machinery from England. The Japanese surrendered in September 1945 before it was ready to be sent. Freed from Stanley Camp in August 1945 Don Russell returned to England to discover what his brother Bob was doing. John Drysdale was released and sailed to Australia to be reunited with his family on 24 September 1945.

Once the B.M.A. landed in Malaya in September 1945, their first job was to take control of the mine. On 12 October the labourers at the mine went on strike, including all the safetymen, the pumps stopped working and the mine flooded. A platoon of electrical and mechanical Royal Indian Engineers were sent to the mine to re-start the pumps but failed due to breakdowns in the electrical supply. It was hoped to recover as many pumps as possible before they were lost under water. At the same time 874 M.E. Company, R.E., took over the mine to produce some coal by mechanical means, and so maintain essential services while the strike continued. In early October, in response to a cable from S.E.A.C., four members of the European colliery staff were flown from England and arrived at the mine on 16 October. They included a chief engineer and Mr. J. W. Elliot, as General Manager of the Collieries, and may have included Bob Russell. They advised the Royal Engineers, who dug out coal at a higher level using diesel mechanical excavators. The strike was settled on the 20 November.

Mr. A. D. Storke, advisor to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, visited in November and said the output was so small that it would be necessary to import coal in 1946 and 1947 to meet Malaya’s requirements.

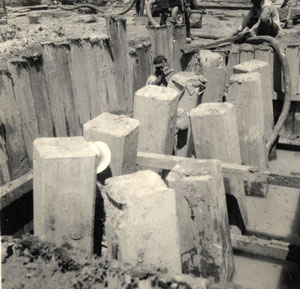

As many labourers were engaged at the mine as possible. The original Chinese and Indian workforce made new castings under the direction of the chief engineer. The pumps were repaired and the electrical supply overhauled. The coal continued to be dug using the Royal Engineers machines. By early 1946 a start had been made to pump out the underground mines as well as producing coal from the two opencasts.

1946

Early in January 1946 William Gemmell was appointed as chairman of J. A. Russell and Co. Kathleen Russell, Archie’s widow had married William in January 1939, William had become one of the Russell trustees by at least 1940. During the war the family had lived in Africa. Clarkson returned to Malaya on 21st January 1946.

In March Mr. J. W. Elliot, the Collieries general manager gave a talk about their rehabilitation on K.L. radio. Giving a history of the mine he said that they were now producing 800 tons a day.

Newspapers reported that conditions everywhere remained difficult. There was a shortage of labour, transport, machinery and food.

The Collieries remained in the hands of the military until 1 April 1946 when it was handed over to the Government. John Drysdale returned to Malaya on 6 May 1946. He recalled that he found the Colliery full of “Banana Colonels” trying to run affairs without any previous knowledge. He found he was unable to use his vote on any matters in connection with J. A. Russell and Co. In June Bob Russell, described as managing director of the Collieries, was quoted in the Straits Times of 1 June '46, saying they were producing more coal than could be consumed. By 22 June J. A. Russell & Co. Ltd. had put a notice in the press saying they had resumed their duties as secretaries to the Collieries. On 1 July the Government returned control of the Colliery to the Company.

J.A.R. & Co. Ltd. held their first board of directors meeting on 5 July 1946. William Gemmell chaired the meeting. The Russell Trustees had appointed both him and Bob Russell as directors. The trustees included Don Russell who was waiting outside the meeting. The minutes record that after Bob tried to raise issues about the trustees William ruled them out of order. Bob then left the meeting and Don joined it. Don tabled a letter clarifying the role of Russell directors and trustees. All the records of J.A.R. & Co. Ltd. had been lost during the occupation. Arrangements were made for a bank loan to repair all the company properties including those at Boh. The policy they had started to try and reduce their debt with the bank was continued. The Collieries with Bob as a Managing Director were refusing to accept the previous agreement that J.A.R. & Co. Ltd. were their general managers and secretaries.” The minutes record that “J.A.R. and Co. Ltd. will take steps to remedy the position.”

On 9th July Bob objected to part of the minutes. By 16th July Bob sent a telegram resigning from the board of J.A.R. and Co. Ltd.

J.A.R. & Co. Ltd. held meetings on 18th July and 30th July and 1st August. They began to sell shares and to start to give allowances to staff and the widows of staff who had died. They resumed the interrupted payments to Dolly Godwin and Pud Swettenham. It was agreed that Russell trustees were advised not to divulge information about the company to any other party. The company still retained a large number of shares in Malayan Collieries, valued at $3,582,000. The meeting of 30 July was an extraordinary meeting for which there are no minutes. By 1 August Don was appointed a director, the Ipoh cinemas and the amusement park were to be sold to Runme Shaw, and other properties were agreed to be disposed of or re rented. William sent his final offer to the Colliery on 31 July and their board was due to meet on 8 August.

William left Malaya on the 6 August. According to Kathleen Russell ‘s notes Bob was told that unless he agreed to 1) Drysdale and Clarkson being on the board of the Colliery 2) J. A. Russell and Company having the accounts of the colliery. 3) Loxleys being put back in their previous position, Bob would be exposed as having been dismissed from J. A. R. and Co. in 1937 and given an annual sum of £4,500. Bob accepted the terms the day before the notice of the Collieries meeting was to go out. He remained managing director of Malayan Collieries under his contract, until 1947.

By the 29th August J.A.R. & Co. Ltd. minutes note that their terms in a recent letter had been accepted by the M.C. Board, that John Drysdale was to be chairman of Board of Directors, and J.A.R. and Co. Ltd. to be secretaries under a five year agreement, to be in charge of accounts, share register, and share holder meetings, for a fee of $3,500 per month, with Clarkson appointed as a trustee to M.C. Ltd. Provident Fund. More property belonging to J.A.R. and Co. Ltd. was sold, and some rents raised. The Sungei Tua estate needed to stop latex thefts, reduce costs, and buy a lorry, while at Boh demand exceeded supply. In the 11 October meeting they were organising compensation from the military for damaged property, selling off machinery at the Sintok mine, and the colliery agreement had been signed on 29 September. On 20 November, they were still selling properties, Boh Tea was selling well, Sungei Tua had made a small profit for the first time, and the bank overdraft was reduced.

The newspapers reported a strike was averted at the Collieries on 19 October, but that several tin dredges were idle on account of the lack of coal. In December it was reported that Malayan railway services were to be cut, the collieries had been on strike and been flooded and if the strike continued electrical supplies would be cut to all industries. The railways made plans to import coal.

The Collieries held an A.G.M. with an extraordinary meeting on 17 December to cover 1941 to 1946 and agreed to pay compassionate allowances to members of staff interned by the Japanese. There had been no trading in shares. John Drysdale presided at the meeting as chairman, and was critical of the Government for fixing the price of coal at less than the cost of production. He said that Malayan Collieries, with about 50 million tons of workable coal, had a life of 70 years at the rate of 2,500 tons a day. Mechanisation underground would be increased and the open cast workings used for emergency reserves. Claims had been lodged with the army for equipment that had been deliberately denied to the enemy and for explosives and earth moving equipment taken over by them, and for losses during the occupation. On 20 December Clarkson, chairing the A.G.M. of Amalgamated Malay Rubber Estates, was equally critical of the Government’s control of rubber prices. Local labour costs had risen, and there were heavy costs of rehabilitation to be met.

On the 10 January the start of 1947 was marked by a demonstration by about half of the 300 men sacked by the Collieries in the previous November. They marched in procession with flags to the Labour office in Kuala Lumpur. Their pay had been delayed by the loss of all the records. A phone call to Batu Arang agreed their pay at an average $3 each. The workers representatives were also asking for 40 days compensation while they had been laid off. Negotiators from the Chinese Consulate were brought in. The labourers were fed at the People’s Restaurant and taken back to Batu Arang in trucks in the evening.

The loss of all records continued to be a problem with many advertisements appearing in the papers for lost share certificates, including those of Malayan Collieries.

Due to mechanical breakdowns and flooding, the low production of the Collieries continued, leading to more calls to import coal. They were producing about 14,300 tons a month in the previous December, but the country’s requirements were for 35,000 tons a month with the railway needing 17,000. Rationing of coal was in force and the railways had cut their services while hours of electricity supply had been cut to mines and other industries. Coal driven tin dredges were trying to covert to run on diesel, using firewood, or lying idle. The chamber of mines had urged the Government to help the Collieries with equipment so that they could produce sufficient coal. Another strike or a flood there and the whole economy would be jeopardised. All the collieries equipment was pre war and had been badly used by the Japanese. It would be several months before the new machinery could be installed. The boilers at Bungsar Power station were being converted to use oil; the railways were using wood and diesel shunters. The imported coal would be very expensive and it was hoped that the situation at the collieries could be improved soon.

Strike The eight week strike at the Colliery began on 18 January. The workforce refused to negotiate until a Collieries workman (Choo Yoon, a coal miner) was released from police custody. The Collieries Union had made twelve demands. They were listed in the Straits Times of 21 January as: “That the Company will withdraw the system of 24 hours’ notice on either side and substitute one months’ notice, pay war bonus as paid by the Government to its labourers, be responsible for lighting and water in the labourers’ quarters, and carry out repairs, provide medical attention and pay wages during sickness, pay immediately eight days’ wages due to labourers for 1941, compensate for losses incurred to 300 labourers who were paid off last November, pay an allowance for changkols, buckets and other equipment used by labourers, release immediately without condition a representative now in police custody, alter the site of the Union’s premises, guarantee that wages will not be reduced in future and that labourers will not be paid off without adequate reason, show interest in the education of the young at Batu Arang and pay extra for work on Sundays and holidays.”

On 22 January the Malayan Union Government offered to arbitrate between the Company and the workforce. The strikers rejected the offer. By 26 January the strikers had sent an ultimatum to the management calling for their demands to be accepted within 48 hours. Chinese servants of European mine personnel had been threatened and had left the mine. The Government stepped in and proposed to take captured Japanese to work there and at the same time to help to resolve the dispute.

On 30 January the district judge at Rawang convicted Choo Yoon , the coal miner employed by the collieries of using force against the police. Normally he would have been sent to prison but the judge, Mr. M. Neal, also noted that there had been mitigating circumstances which included insufficient notice to quit his home, and threats made to him in letters. “Everything was done to inflame these poor people” he said.

The 200 Japanese sent to work at Batu Arang produced only 50 tons instead of the expected 500. Additional Japanese labour was sent.

Discussions between the Government and the Malayan Collieries Workers Union attempted to negotiate for arbitration. By 7 February it was agreed to have a judge as chairman, and four other members as long as the Japanese workforce was withdrawn. The Arbitration Board was agreed by 11 February. It consisted of Mr. Warren, Manager in Malaya for the Anglo-Oriental Malaya Ltd., and Mr. Mills, Manager of Selayang Tin Dredging Ltd. to represent the Collieries and Mr. Lam Swee and Mr. C. S. U. K. Moorthi, the vice-chairman and secretary respectively of the Pan-Malayan Trades Union Congress, to represent the strikers. The sessions in the council chamber would be open to the public. By 13 February the day before the arbitration board began its proceedings the papers reported that 21 tin mines were not working, and 8,000 tons of coal from India was expected. Local engineering companies were attempting to build machinery to convert tin dredging machines to run on oil.

The Arbitration Board. Justice Pretheroe, presiding, helped the trade union, who were unfamiliar with the procedures, to present their case. Their case was put by four representatives—Mr. Hoh Cheng, President of the Union, Mr. Yap Khun, Vice-President, Mr. N. G. Pillai, Treasurer, and Mr. P. K. R. Kurup, President of the Indian Section of the Union. Mr. R. C. Russell, Managing Director, and Mr. J. W. Elliot, General Manager of the mine presented the Collieries' case. The trade union presented their twelve demands to which the Collieries gave a detailed written reply. To the first demand of one month’s notice, rather than 24 hours, the company replied that they gave a minimum of 10 days notice, and that they had the right to stand off workman for temporary periods, they were not dismissed but would resume work when conditions at the mine permitted. These men would not be paid as events like floods often stopped the work and it was considered a fair risk in coal mining businesses. Many of the miners were subcontracted and their contracts agreed by Kungthau. The mine had no list of the workforce and because the Kungthau submitted the same set of names while interchanging personnel it was impossible for the company to have a record of the true facts. They considered it essential that they now employed labour directly and have a complete list of the labour force. To the second demand for back pay, the company said they had asked the union to prepare a list of employees, which it had not yet done. The third demand for repair of housing, water supply and lighting, they had already agreed to and were doing all they could. There were shortages of materials. They had asked the union for specific instances, because large numbers of people lived at Batu Arang who were being supplied with electric light and water free of charge, which the Company was not prepared to give to people who were not employed at the mine. The hospital already supplied free medical attention to all employees. It was considering introducing sick pay but was awaiting the decision of the Malayan Mining Employers Association as a whole. The fifth demand for eight days wages from 1942, they refuted saying that all wages were paid up till 5 January when the company withdrew from the mine. The company said it was not responsible for the sixth demand for compensation for the 300 workers laid off during last November. To the seventh demand for tools, they replied that all directly employed workers were provided with tools, but not those provided by sub contractors. The eighth demand for union premises the company refuted. The ninth demand for pensions, they said they were prepared to consider once they had a full list of their employees. All workers would have to be registered first. The tenth demand for schools the company said had been fulfilled for many years already. The eleventh demand for a 48 hour week, paid annual leave and public holidays, the company said they would institute whatever solution the Malayan Mining Employers Association would agree to. The final demand for co-operation between employees and the Company they said could not be obtained if the company was constantly threatened with strikes. They were prepared to go to arbitration but not prepared to pay money to those on strike since that would be to encourage perpetual strikes. The employees witnesses were then questioned, Mr. T. K. R. Kurup, Chairman of the Indian Section of the Malayan Collieries Workers’ Trade Union, was in the witness chair for more than nine hours. Bob Russell questioned him. It was revealed that the union had not held a general meeting but had spent four days canvassing the opinion of different occupational groups. The groups had elected 250 representatives to decide on the demands. The meetings were held in the open air, no check was made to stop infiltration of outsiders but they made sure that all those who voted worked for the Collieries. None of the 16,000 population of Batu Arang were excluded from the meetings. Mr. Moh Chong, a fitter and President of the Collieries Workers Trade Union, gave evidence about living conditions in Batu Arang, saying at least 80 % of the living quarters were in sate of disrepair, the latrines had no roofs and no longer flushed, the water was unfiltered, and roads needed repair. Most of the huts built by the Japanese were leaking. He said wages had been reduced, there were no facilities for school age children, he had to work rest days in order to live. They wanted the same conditions as Government workers, paid holidays or overtime for work on public holidays. He was cross-examined by Bob Russell. He said the school could only provide education for 500 children. Bob pointed out that employers were required to provide education and medical facilities under the Labour Code and that the company had never been fined for not complying, and that the union had never told the Government that the provisions of the labour code were insufficient. The evidence for the Collieries began with Mr. G. A. Keymer, Chief Accountant, who described the wages system. The Kungthau was responsible for gang labour. Wages were handed in bulk to him after completion of a specific job. Under this system of pay by quota of work it was “impractical to pay sick labourers”. He said he had not been give the information about the 300 people laid off in November and it had made it impossible for him to calculate their wages. When the Chairman of the Federation of Trade Unions had visited the mine and induced the kepala to supply the information then he had been able to draw up the pay sheet and pay off the labourers on 16 January. The union had only one interpreter who was explaining Mr. Keymer’s replies to the representatives and at the same time recording the proceedings. The judge was not sympathetic saying that the Government was paying for the proceedings and that the union should bring their own interpreters. Mr. Keymer said that the 300 laid off had been given 10 days notice. The next witness was Mr. R. G. Pash who looked after housing and education affairs at the mine and was employed by J.A.R. and Co. Ltd. He said the water was filtered and the company provided 300 private dwellings, supplied with water and electricity free of charge. Flush latrines were repaired after the war but vital parts had been stolen and it was difficult to obtain replacements. No register was kept of company employees, and many non-employees lived at Batu Arang. The Company has spent $50,000 repairing property at the end of the previous year. All labourers, even outsiders, were treated at the hospital. The ambulance had its vital parts and tyres stolen repeatedly but was in good condition. They did need a new qualified nurse and doctor and had approached the Government for help and had advertised. The judge agreed that there was a great shortage of medical staff at the moment. A nurse attended the 35 to 48 births per month at the mine. There had been no deaths. New premises had been proposed for the union to use. The company had built a Tamil school, which had over 200 pupils. They contributed towards the maintenance of the Chinese school. The next witness was Mr. G. Hinchcliffe, a mining engineer at Batu Arang. He said it was customary that mines here and in the U.K. sometimes closed due to fires or other accidents. Labourers would then be laid off without notice. It was a normal risk attached to the industry. He knew that the mine had been worked by the Japanese who had employed a bigger workforce and felt that the employees had not suffered financially during the occupation. He said that wages were computed every day before the evacuation and everyone who came to the office was paid. Unclaimed wages were given to representatives of the union at the police station. He compared the work rates of miners in the U.K. who could mine 3 tons in a shift while the same shift at Batu Arang produced one ton. He said that labourers in Batu Arang worked an average of 22 or 23 days a month and underground miners worked an average of four and five hours a shift. There were 400 to 500 underground workers in Batu Arang, compared to 15,000 to 20,000 prewar. Mr. J. W. Eliot, General Manager of the Malayan Collieries Ltd., was next on the witness stand. He agreed that in future it was desirable for all labourers to be employed directly by the company and registered. The next witness was Mr. J. A. Brazier, Trade Union Adviser for the Malayan Union. Mr. Brazier was questioned on the differences between conditions for miners in the U.K. and in Malaya. Commenting that employer and employee consultation schemes had reached a more advanced stage in the U.K., he said that no employer would be foolish enough to reduce wages without consulting the appropriate union. The judge asked the Union if they had any objection to the registering of labour by the Collieries. He had toured the mine the pervious day and found many people in company’s quarters that had no connection with the company. The Union had previously objected. Bob Russell said that on the basis of the ration cards there were 18,000 women and children at Batu Arang. The board then adjourned for its findings. These were given on 28 February in a 12-page judgment. They rejected the demand for back pay, but agreed to a 48 hour working week, overtime rates and 3 public holidays a year. The judge said that the strike should have been called only after a secret ballot, and urged that the company must have a system of registration of labour. “The fact that the Company does not know its own employees is a cause of grave mistrust between the two parties.” said the Board who also suggested that every employee should be given a printed copy of his service contract before starting work for the Company.” Further discussions were held on 3 March when the union were unwilling to agree to registration of employees without taking it back to the workforce first. It was agreed to put it to mass meeting on 4 March and convey the result to the Company by 2 p.m. on Tuesday. An agreement was reached by 9 March after an all day meeting. The Company had been temporarily taken over by the Chief Inspector of Mines as a competent authority during the strike and was handed back on 17 March. 1,000 Japanese personnel were withdrawn.

A leader article on the Pan-Malayan Federation of Trade Unions in the Straits Times of 20 March pointed out the differences between unions in Malaya and Singapore. The writer feels that the involvement of the PMFTU had prolonged the strike at Batu Arang, partly due to their inexperience. It was not a democratic body like the TUC in the UK. The writer feels that the Malayan Communist party is using the trade unions for its own ends.

On 30 March John Jeff went on leave to the U.K. and the Straits Times says “It was Mr. Jeff who was mainly responsible for bringing the dispute between the Malayan Collieries and its employees to arbitration and final agreement. He spent many hours with the Collieries workers’ trade union discussing points they had raised. Before the war, he played a leading part in negotiations connected with several big strikes in Singapore”.

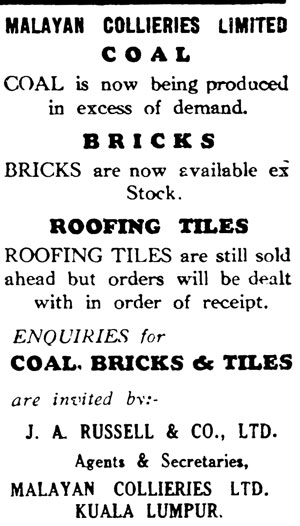

By 26 April, the Collieries put out a circular saying that it would be able to supply all the coal that the country needed from 1 July. The price would continue at $18 a ton although this was lower than the cost of production. In May the company advertised for staff to maintain the roads, houses and sanitation system at Batu Arang. By July the Collieries were able to advertise that production was in excess of demand. This notice was signed J.A. Russell and Co. Ltd. Agents and Secretaries. So it may be that they had returned to their former role.

An article in the Straits Times in July covered the 30th International Labour Conference being held in Geneva. William Gemmell was the South African employers delegate. In his opinion workers in the South African gold mines were not educated enough to be able to organise into trade unions.

In late July an official report stated, “New machinery designed to raise production to 2,500 tons per day, as against the pre-war 1,900 -1,950 tons per day, and estimated to cost $3,000,000, has been ordered for use in Malayan Collieries, but that it is unlikely to be fully installed until 1949.”

On 20 October there was a countrywide strike for one day. Rubber estates and mines including the Collieries came to a standstill. The Straits Times reported the following day that “At Batu Arang, 2,000 labourers had taken a holiday after having previously informed the management of their intention” The paper was dismissive of the cause of the strike, not explaining its reasons to their readers. (See left)

In December the annual report of the Collieries, said that capital had been spent on underground mining equipment that was covered by a rehabilitation loan from the Government. They had submitted a claim for more than $7,000,000 from the War Damage Claims commission. The eight week strike had raised the wages of the employees, but the rate of production per person had also risen. By the end of the year the relationship between management and labour was good. John Drysdale chaired the A.G.M. and announced the negotiations with Portland Cement. The eight week strike meant that coal was being sold at a loss at $18 a ton. The costs rose to $20.50 from November. Coal was now being produced in excess of requirements and surplus coal could be exported.

The Collieries was one of 280 major strikes in 1947. 696,000 working days were lost through labour disputes at rubber estates, tin mines and at the Hydro-electric power company.

The All Malaya Hartal, October 20, 1947.

The Hartal was part of a campaign of Civil disobedience, (the idea borrowed from the Indian National Congress, ) by the PUTERA-AMCJA against the constitutional proposals for the new independent Malaya. They had lobbied London with an alternative "People’s Constitution” without success. The strike was planned to coincide with the opening of the session of the British Parliament where the Revised Constitutional Proposals were to be tabled and debated.

The Emergency

(Called by the Communists: "The Anti-British National Liberation War". A detailed chronology of the Emergency can be read here. )

Protests became increasingly militant. By June there were 23 strikes in the country. On 16 June three European managers were killed in Perak. Emergency measures were brought in. The communist party and some unions were banned and new powers were given to the police including arrest without trail and the ability to deport people. Managers of estates asked and were given licences to carry guns and some were given guns by the police. The Malayan communist party retreated to rural areas and began a guerrilla campaign targeting mines and rubber plantations.

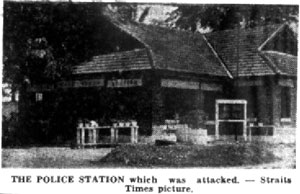

Batu Arang was attacked on the morning of 12 July and was occupied for nearly an hour. In a well-planned attack, the telephone line was cut. Between 70 and 100 Chinese raiders attacked and five Chinese were killed, including Ng Peng San the chief mining overseer, Kow Cheok, a business proprieter in the town, Chan Kum Yuen a clerk, and a lorry diver and a foreman fitter. The police station was fired on, a railway train stopped at the station, and a bus held up. Three excavators were damaged. The driver of one was ordered at gun point to drive his machine into the pit but it got stuck 20 feet below the edge. Eight trailers were damaged, as were the water pumps.

In the Straits Times on 14 July a shocked leader article revealed that the manager of the mine had asked for troops but the Ghurkhas had not arrived although now a military guard had been sent. There was a need for wireless communications and soldiers. Nearly all European women and children were evacuated from the mine, and 20 people at the colliery arrested as part of police investigations. On the 13th the colliery produced half its normal output, but it was back to normal by the next day.

In late July RAF spitfires were being used to attack the communist camps. Communist areas included the jungle near Batu Arang, which was targeted for attack by combined police and army forces at the end of July. There were fears that events in Berlin and the crisis in Malaya were part of a greater scheme to declare it a communist State. The shooting of planters and miners of many races continued, as did the attempts to stop the perpetrators. International tension continued through August and September.

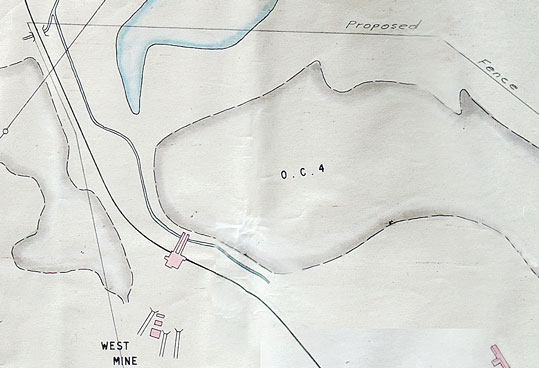

In October the Collieries introduced a registration scheme to cover everyone living or working in the district. The coalfield covered 9,000 acres and included areas where communist guerrillas could hide. All 2,500 employees were registered and also their dependents over the age of 12, as well as all the shopkeepers. Every house and property was also listed under the threat of it being demolished. Anyone without a card, (which carried his or her photograph and thumb print,) after 1 November was liable to arrest. The market area was enclosed with a security fence with the only entrance by the police station. Only those with cards could buy or sell there. As a result about 5,000 people left their huts and smallholdings and moved out of the district.

The Collieries A.G.M. announced for December listed the directors as John Drysdale, (chairman), Erroll David Shearn, John Harrison Clarkson, Francis Scott Mc Fadzean, (Government Nominee), William Morley Warren, and Herbert Willoughby Moxon, with J.A.R. and Co. Ltd. as Agents and Secretaries. The report said a final agreement on the cement works was expected soon. Two technical experts from the British Cement Co. had spent some time in May looking for the best site for the works and sources of raw materials. The damage to the mine in July had been repaired and stripping operations recommenced. The two underground mines would begin to break new ground. The claims from the army for explosives had been settled but the claim to the RAF for earth moving equipment was still being discussed. A lot of new mechanical equipment had been installed. Parts to repair the excavators had been received. There was a dividend of 5%.

However despite the new security arrangements Mr. Song Keng Sing, 57-year-old housing clerk for the Collieries, and his 22-year-old-son, Mr. Song Wai Leng, were shot and killed in their home near Batu Arang in early December.

1948

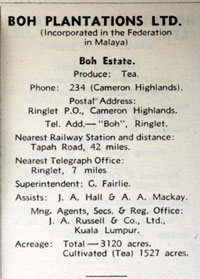

At the start of 1948 conditions for the Collieries were beginning to improve. Bricks and Tiles were being manufactured again and plans for the cement factory were nearing completion. Mr. J. R. F. McKenzie, Assistant Managing Director of Portland Cement visited Malaya for three weeks to consult with the Collieries Board. The Collieries owned land in the Kanching Hills that would provide some of the raw materials.

William Gemmell writing to Tristan Russell about his father’s company, listed five facts: that Sugei Tua was making only a small profit, that Boh was suffering from the kaleoptera pest but should make a profit of $120,000, the tin mines had not got going again, the Collieries would not declare a dividend until 1949 and a 20% income tax was now in place. He expected that J.A.R. &. Co. Ltd. would have a dividend of 5% with possibly 10% in 1949.

The Government reported at the end of February that Batu Arang could provide all the country’s domestic requirements, and imported bunker coal from India was no longer affected by strikes. There was another one day general strike in April in Singapore which the Straits Times observed had “ Communist manifestations” but they appeared to be confident that the police could deal with “unlawful elements which practise intimidation and coercion to keep willing workers from their jobs”

More optimism came in May when the arrangements for war insurance claims were announced. The market in shares were reassured by “by the stern attitude taken by Government in support of the Singapore Police in their heavy task of thwarting the lawless acts of unproductive elements who seek to create disorder under cover of the trade union movement.” However over 1,000 of the dock workers struck at Port Swettenham in early May and a court of inquiry was set up to deal with the dispute. One of its members was Mr. Elliot, General Manager of the Collieries. Portland Cement’s announcement that the company would invest £800,000 in the cement factory boosted Malayan Collieries shares.

1949

The Collieries sent a letter to the Government in February 1949 with a history of the Company and details of the 1947 strike and its resolution. The K. L. archives has no covering letter with these pages. Records at Kew refer to a petition from the Collieries to the Colonial Government. These records could refer to the compensation claim for damages because of the Government’s admitted failure “ to provide against the attack on the mine in July last year." The notes include the fact that the distillation and plywood plant were now derelict, but the tile works was producing “1,000,000 “Marseilles” type roofing tiles per year, using clay obtained mainly on the property.” In January the papers reported that four Scots Guards stationed at Batu Arang had become drunk on New Year’s Eve and broken into three huts occupied by Colliery employees. Three were sent to prison for two years.

There was increased bandit activity and in January about 20 guerrillas stopped a timber train on the Collieries’ line. 50 woodcutters and the crew were told to leave, the lines were damaged and the train derailed and left with some of the wagons at the bottom of an embankment. The collieries required assistance from Malayan Railways to lift the engine. Gun battles between the police and the guerrillas continued.

Despite the 300 Scots guards at the Batu Arang. Kenneth Clarke, the 28-year-old opencast superintendent, was shot dead on the morning of 28 January as he travelled by jeep to the south mine. He had only started his job a month previously. He was the seventh European killed in Selangor and the authorities believed it was the same group who had derailed the timber train. He was found alive by Mr. Elliot the general manager, by his jeep, which had ten bullet holes in it. He died in the hospital two hours later. Two more Europeans were killed in an attack on a tin dredge at Serendah.

The Collieries advertised for a new open cast superintendent in February along with a property inspector, a mining overseer a milling machine operator and two fitters. Share prices in coal and tin dropped, the financial correspondent of the Straits Times commenting that “they were affected more particularly …by the ever-lengthening list of civilians murdered by bandits in the Federation of Malaya. Nor were operators impressed by the official statistics offered as proof of improvement that, whereas 48 civilians a month were killed in the second half of 1948, only 31 were murdered in January."

In May events in China shook people’s confidence and they appear to have little hope that the U.K. Government under Attlee would give them more assistance. On 20 May a police and army party were ambushed near Batu Arang; two British officers, and a Malay police colonel were killed and four other British soldiers seriously wounded. They had been outnumbered two to one and shot with Bren guns. They lost some of their weapons to the gang who withdrew into the jungle. On 24 May the Government responded with RAF planes bombing the area throughout the week and Scots guards patrolling the ground. A well-fortified camp was discovered at Bukit Mayong four miles south west of Batu Arang.

Unions

In June the Colliery Asian Staff Union, urged their members not to supply the bandits with food and help. With no ID cards guerrillas returned to Batu Arang for help from their relatives and sympathisers. The union asked their members to have faith in their government to protect them.

In July two Straits Times leading article’s covered the 1948 annual report by John Brazier, the pan-Malayan Trade Union Adviser. At the beginning of 1948 there had been 500 Unions, many dominated by Communists. When the leaders went to the jungle the unions collapsed. 159 were abandoned, 40 dissolved and 118 cancelled by the Registrar. But a minority carried on and remained true to their constitutional objectives. Unlike other countries where unions had been either crushed as in Spain, or become part of a communist state, in Malaya they followed the model used in the West. The unions that had survived were made up of Indian Estate workers, employees of Government Departments, Chinese engineering workers, clerks and the employees of Malayan Collieries. At the end of 1948 there were 156 registered unions with a membership of 70,000. This represented a tiny proportion of the workforce. But the fact that they had kept themselves independent during the unrest meant they had done so at considerable personal risk. A police permit was needed to hold a meeting of more than five people, and the more skilled grades of workers were more likely to form unions. At Batu Arang the Chinese section of Collieries’ worker’s union had collapsed but the Indian workers union had survived. Mr. Brazier commenting on employer -Union relations at Batu Arang during the second half of 1948 said: “Both parties were in constant touch with the Trade Union Adviser’s Department, and, because they were able to understand each other’s point of view, many important problems have been solved. This is a splendid example of what can be achieved, in spite of the emergency, when a progressive employer is in charge.” In it’s final paragraph the report said: “If the lessons of 1948 are read rightly, it would not be too much to say that Malaya, the Government and the employers of labour owe the trade unions a great deal of gratitude for their conduct and their efforts during the latter half of 1948. They have ably demonstrated that they are not subversive or Communist organisations; they have repeatedly asserted their support of the Government in the campaign against terrorism and violence; they have played a great part in the industrial economy of the country without major disputes or disturbances, and in so doing, have given invaluable aid in maintaining the production of the rubber and tin so necessary to the economic recovery of Malaya.” The Straits Times commented: “The desire of this solid core of organised workers to organise freely and along lines best suited to the Malayan conditions is one that must receive the support of all people who recognise the fundamental right of free association. … No one can study the report which we have been reviewing without seeing that the Trade Union Adviser’s Department is the most energetic, the most purposeful, the most effective agency for spreading the principles of conciliation and compromise that is at work among the wage-earning classes in the Federation today. It is strange that some people cannot see that—and see its supreme value at a time when violence and murder are stalking the land.”

In October John Drysdale and E.D. Shearn, (who was the President) were present at the annual meeting of the Malayan Association in K. L. They discussed the use of Citizens committees and auxiliary police forces trained by the police.

The Collieries opened a new Chap Khuan Chinese School at the cost of $60,000 for 2,000 children. It had been established 30 years previously. There had been four small unauthorised Chinese schools before the emergency, three run by communists according to the paper. It joined the Indian School and a private English school. At the opening of the school John Drysdale advised the children to ““ keep communism out of your homes”. After they had left children would be encouraged to work for the Company and given training under an apprenticeship scheme.

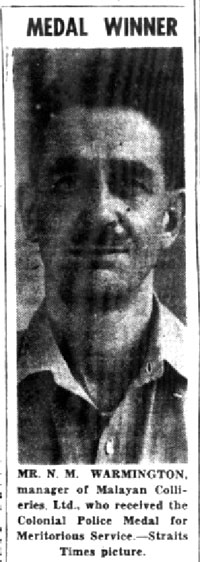

The 31st AGM of the Collieries took place in December. They announced the appeal for compensation for the damage caused in July 1948. Coal production for 12 months ended in June was 388,416 tons, 63,454 tons more than in the previous year, but still not sufficient to meet demand. John Drysdale said that many of the leaders of the Chinese section of the Union had gone into the jungle and were believed to have taken part in the attack on the mine. The Colliery had been generally restored and profits were $1,101,841. A dividend of 10% was approved at the meeting. Mr. Elliot “had resigned for private reasons” and been replaced by Mr. N. M. Warmington who was Deputy General Manager. The Collieries advertised for 200 more underground workers required for the next 6 months.

Cement. Despite the emergency it was agreed that the cement works would go ahead covering 200 acres and employing 200 people. The emergency delayed it and details were still to be finalised in December.

1950

The Chinese Communist Government was recognised by Britain, and on 25 June 1950 the war between North and South Korea, which had been divided in 1945, began with the Communist North invading the South.

The Collieries continued to advertise posts during the year. A storekeeper in February, and November, a bookkeeper in May, a Security Officer in July, an assistant engineer in September. An interview with Amy Martin, from Yorkshire, the fiancée of a new employee Mr. Amos Doley, who arrived in April, showed a picture of the couple saying that they were not afraid of bandits and that Batu Arang was one of the safest areas in Selangor.

In March the Collieries put out tenders for the construction of 32 brick built houses for the work force.

Flags and Posters were put up in celebration of May Day by communist sympathisers; Chinese found with pots of glue and anti British posters were arrested. At Batu Arang the Union asked for a sports day and tea party to celebrate but the police refused permission. Instead the workforce was given the day off.

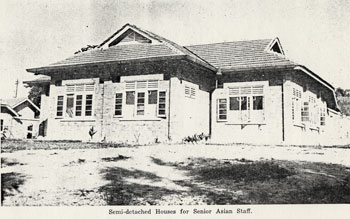

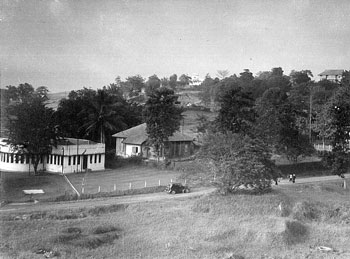

The 32nd report of the Collieries said they had had great difficulties in getting sufficient labour, large sums had been spent on modern mining equipment and the first stage of a three year plan to build improved the workers housing. All the children of the workforce would be able to attend school and adult education had been started on a small scale. The Colliery profits had increased by 31 %, $1,088,903 for the year. Output was still not meeting demand. There had been a fire in the West Mine that had reduced output. The prospectus for Malayan cement would be issued soon, with a block of shares reserved for the collieries. The works would be built at Rawang. The correspondence re the claims for damage to the earth moving equipment continued. The annual report was accompanied by an illustrated booklet, printed in October which contained a detailed description of the Colliery and can be read here. Some of the photographs from the booklet (below right) which show the successful reconstruction after the war.

On 1 December John Clarkson, executive director and manager of J. A. Russell and Co., and director of Malayan Collieries and of Boh Plantations was shot in an ambush at the Sungei Tua rubber estate. He was the first company director to be killed since the start of the emergency. He and an Indian Special constable died. Ten bandits surrounded them, and Clarkson fired all the chambers of his revolver before he died. He was buried the next day.

In about 1953 John Drysdale was also targeted by the guerrillas. He took the same route from K. L. to Batu Arang every day. His life was saved by Chong Kim Voon, who warned him of the ambush, the police were contacted and picked up the communists.

1951

The Emergency There were more attacks on Batu Arang in 1951, 70 bandits derailed another train in January, two special constables were killed and six were wounded. Flaming torches of dry vegetation were thrown down the embankment onto the train. A camp was found nearby. On 6 October the British High Commissioner, Sir Henry Gurney was ambushed and killed. In November all responsibility for the Emergency were given to Gen. Sir Rob Lockhart, the Director of Operations, making him a supreme commander of all troops, the police, home guard and civil defence. There would be a planning committee of three from the civil service, police and army. Neither the War Council nor the Federation Executive Council was consulted on the new arrangements, and even more sweeping changes would be announced when the General arrived.

Malayan Collieries The monthly output of coal was 10,000 tons short of demand. The biggest problem was extra labour. There was work for several hundred more labourers, if they could be recruited, to work in the underground mine. The tin mines were using large amounts of coal due to their post war development. With the rising cost of firewood the tin mines considered importing coal from Indonesia although it cost twice as much as Malayan Collieries coal. The collieries produced 33,000 to 36,000 tons a month. Tin mines alone consumed about 7,000 tons a month. Other large consumers were the Malayan Railways and the Perak River Hydro-Electric Power Co. Ltd. Consumers were resorting to fuel oil and wood to supplement their allocations. In July former Ghurkha soldiers arrived at K. L. airport from Rangoon. There were among 40 employed by the Collieries to guard the mine and more would be recruited as miners due to the shortage of local labour. In the 33rd report John Drysdale admitted that output was at a disappointingly low level, but they were unable to find more labour. They made a profit of $526,850 and a dividend of 10 per cent was recommended. The price of coal had been raised to $25 per ton on the 17th of October. The company had increased its production of bricks and tiles. They had spent $128,000 on Emergency measures and another $153,000 on housing for labourers. They continued to advertise for staff, a clerk in February, and a storekeeper in April, along with a hospital assistant, a junior clerk in July, and a stores officer in December. Efforts made to import more skilled Ghurkha labour from Rangoon were unsuccessful.

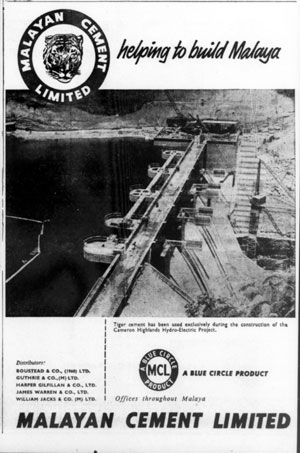

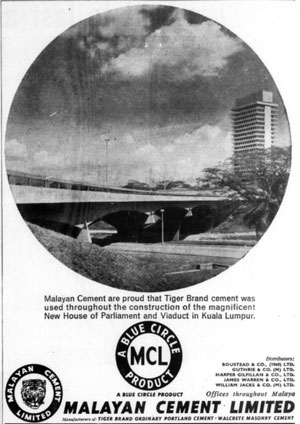

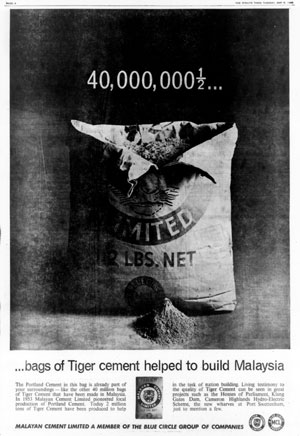

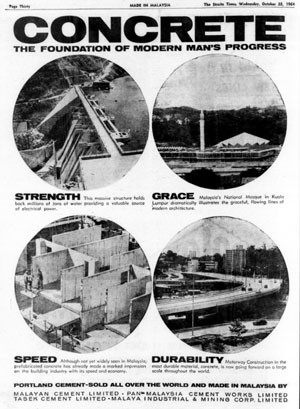

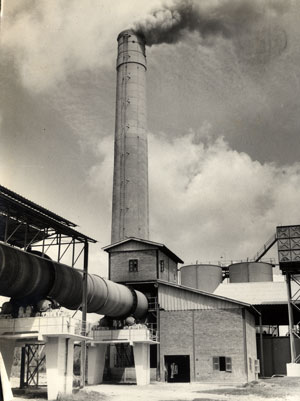

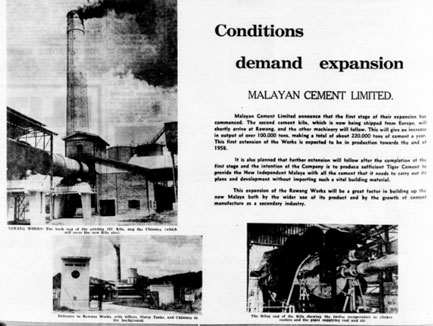

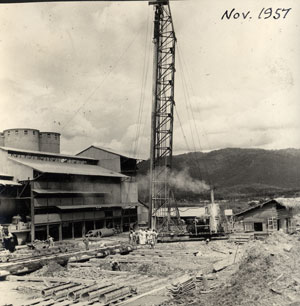

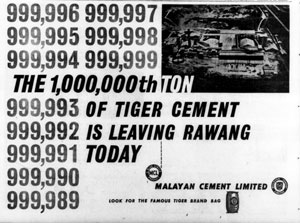

Malaya’s First Cement Works. Just before Easter the Collieries sent shareholders notice of the shares in Malayan Cement. The company had been registered in Malaya with a capital of 10,000,000 shares of $1 each. Malayan Collieries Ltd. was allotted 442,500 fully paid Founder shares. The prospectus was issued in April. Production was expected to begin in 1953. It was based at Rawang because of the limestone quarry sites there. Coal, shale and clay would arrive by train from Batu Arang. Gypsum would be imported from Australia. Arrangements were in hand for the purchase and erecting of the plant. It would be Malaya’s first cement works and the first big flotation since the war. Malaya imported 200,000 tons a year, of which 85,000 tons were used in the Federation. The works would be able to produce 100,000 tons a year. The first meeting of Malayan Cement was held on 14th August, at the offices of J. A. Russell and Co., “General Managers and Secretaries”. John Drysdale the Chairman said at the meeting that they had intended to float the company in 1950 but the Korean War intervened. Work had commenced on the site in June and contracts for work and material had been placed locally. Portland Cement had ordered the plant and equipment in the U. K. The first A.G.M. was held on 13 December. Piling work was completed for the factory by then, security measures installed, and access roads and rail sidings were being built. The first quarters for staff were nearing completion.

Boh Tea In April the Straits Times published correspondence about the high price of tea leading Boh to write to the paper explaining that costs had risen in recent months, due to materials, services and wages. Rubber producers had increased wages and Boh had been forced to do the same to keep their workforce. They pointed out that the price of local tea still compared favourably with imported blends. In further correspondence Boh rejected the implication that they were profiteering saying that “our prices are from approximately 40 cents to $1 a pound below those of comparable imported teas.” The London Tea market reopened in April and Boh had 30 chests at the auction,” the average price of 3s. 9 ½ d., being about equal to that paid for Assam teas.” On 1 May Boh announced “Boh tea is $2.60 a lb. and the price of Tiger tea $2.25 a lb.”

1952

The Emergency On 22 January 1952 Winston Churchill appointed Gerald Templer British High Commissioner in Malaya to deal with the Malayan Emergency. He is credited with creating a model of counter insurgency by concentrating on intelligence. He said, "The answer lies not in pouring more troops into the jungle, but in the hearts and minds of the people”. New villages were built where Chinese were settled away from bandit activity, citizenship was granted to many residents, and a system of rewards for surrendering rebels was instigated. He left Malaya in 1954.

Under the emergency 25 shops at Batu Arang were closed by the Government. The shop's proprietors appealed against the decision. One of the Government’s Emergency Powers was to take control of businesses if profits were likely to go to bandit funds. The chairman of the committee formed to help the Malayan collieries strikers Hean Choong was killed in June. He had also been secretary of the Rubber tappers union in Rasa. He was killed trying to resist capture according to the newspapers. In August Ghurkhas found a large bandit camp. A gang set fire to one of the Malayan Collieries vehicles.

Batu Arang The Collieries were still short of staff and advertised for a shorthand typist, assistant storekeeper, welfare officer and a hospital assistant in January, a cashier in February, and a bookkeeper and stenographer in July. They were still advertising for a cashier in August along with a new master for the Chinese school. The Collieries was one of three European firms to set up industrial training for young Malayan men. The 34th A.G.M. was held in November. They began to sell large amounts of industrial equipment including two steam locomotives. Their report recorded that low output was caused by shortage of labour. They were trying to train suitable Malay labour, but Malayans didn’t like working in underground mines. There had been a 13% drop in production partly due to the increase in the thickness of shale that had to be removed from the seams of coal in the open cast mines. Advertisements indicate that Guthrie’s was the Agents for the sale of Malayan Collieries Malatiles in January.

Utan Simpan Rubber went into voluntary liquidation in January. This Company had been started by J.A. Russell and Co. and they had some interest in it, possibly in shares.

Cement By 1 March John Drysdale reported that the road access to the cement works had been completed and security was in place with a permanent police post. The plant was expected and production would begin in the first half of 1953. The cement works advertised for an engineering draftsman. The second A.G.M. was held on 13 March. Four jobs were given to children from the Serendah Boys Home that was run by Save The Children.

In December it was announced that the Federal Advisory Board for 1953 would include John Drysdale as an employers representative.

Malayan cement advertised for a chief chemist in January, and a foreman in April. Their third A.G.M. was held in April.

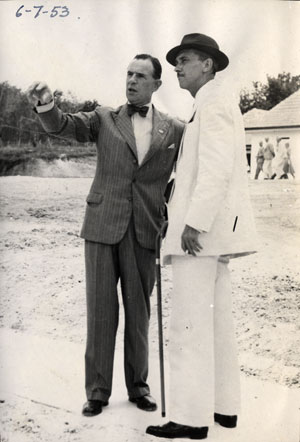

"There is to be a big opening on July 6th, with 300 guests including Sir Gerald Templar & the Sultan. Drysdale is Chairman of the Company & will make a speech." William Gemmell writing to Tristan Russell in May.

Mr G. F. Earle of Portland Cement arrived for the opening on 3 July. He was reported in the paper as planning to give as many important jobs to local people as possible. Positions at the factory would be divided equally among Malays, Chinese and Indians. The factory would produce 100,000 tons of cement yearly, and all the cement would be used in Malaya.

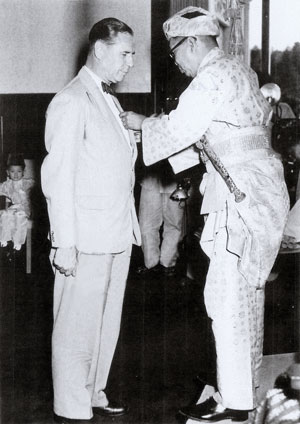

Sir Gerald Templer, flying in by helicopter, declared the factory open on 6 July. He said it demonstrated returning confidence in the country.

John Drysdale spoke of the harmonious way that all races had worked together on the construction.

Left: Drysdale shows Sir Gerald Templer round the factory.

Sir Gerald Templer’s wife lent her name to an appeal for the Tuberculosis Hospital in October.

Demand for Coal falls. Malayan Collieries fails to pay a dividend.

Gen Sir Gerald Templer had visited Batu Arang in January. He spoke to officials at the Colliery saying that 95% of people in Malaya were against the Communists, but they were afraid to show it. If they could get the whole community, Malays, Chinese, Indians and Europeans to be behind the Government and “to come out boldly and say we don't want Communism then we would get the Emergency over with and get on with our real job" It was he said, tragic that money which would have benefited the people was being spent on barbed wire and bullets. He reminded the audience that by and large the standard of living in Malaya compared favourably with any other country in South-East Asia.” We have a lot to be proud of in Malaya," he said. The Collieries advertised for a mining superintendent for the opencast in March, on a contract for about 3 and half years, and for supplies for the Chap Khuan School in April. In May one of the items they were selling was an armoured car.

William Gemmell wrote to Tristan Russell in May saying: “Boh, the Cement Works and Kampong Malacca land are all right - the cement Coy will I think be a most successful enterprise, the Collieries look very unsatisfactory, not so much from the working aspect, which is at last on a sound and promising basis but because our chief consumers, the Power Companies, are now going to use heavy oil (diesoline) which has fallen in price far below our coal prices. The railways are thinking of switching also & if they do it will be impossible to run Batu Arang except on a very much reduced scale, with unfortunate financial results not only to the Collieries but to J A R & Coy Colliery section, which pays more for our administration charges, not to say the dividends in the JAR Coys, 530,000 $1 shares in Collieries, which have been 10%....

The Collieries 35th A.G.M. was held in December. Their profits were $16,770, compared with $331,287 in the preceding year, and there was no dividend. Shareholders wrote to the papers critical of the company although several were sympathetic , one writing: “the country cannot afford to see this valuable undertaking on which the Government has relied so much in the past deteriorate into an unprofitable venture, after years when its product was sold by Government order at prices well below what imported coal then cost. Strikes, labour shortage, lack of security, terrorist attacks and other troubles have driven profits away and the company now deserves to receive a little more consideration from Government, financial and otherwise. Had Archie Russell lived the company might have steered a more profitable course.”

The board at this time consisted of John Drysdale, Chairman, F. H. Atkinson, A. E. Llewellyn, D. T. Waring, F. G. Charlesworth, V. E. Davies (a Government nominee) and J. A. D. Morrison who was appointed in October. Mr Morrison was manager of the Hongkong and Shanghai banking Corporation.

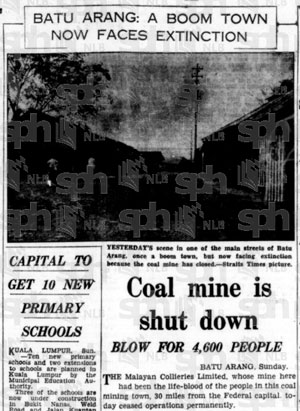

At the A.G.M. John Drysdale blamed the Government for not coming to a decision about fuel for the railways and the electricity generating board after five months. Oil was available at 1941 prices and they were unable to compete. He said; "If all consumers change over to oil, there will be no need for coal, the colliery would have to shut down and the company go into liquidation," he said. "Such an expectation is unreasonable and unrealistic. "So far, it seems that the problem has been regarded by the Government on a cold price basis, but there are other considerations. "The colliery has built up a township 2500 employees and about 9,000 residents, all of whom are dependent on the industry for their livelihood. "Already hardships are being experienced as a result of dismissals of men who can no longer be economically employed." At the state council meeting in December it was reported that 473 workers at Batu Arang had been sacked and 100 more would go before the end of the year.

1954 The Decline of the Collieries

Coal output fell in January. The railways switched to using oil fuel for their locomotives and machinery. 60 engines had been converted by February. Power stations were doing the same. Talks with the Government continued inconclusively and shares dropped continually as talks continued through February and March.

At Batu Arang 14 shop houses were demolished so that the Chinese school playing field could be extended. They were temporary buildings that dated from the Japanese occupation and the new houses or businesses remises were found for their occupants.

300 more workers were told there was no more work for them in March. More than 800 surface workers had been dismissed since October. Coal had piled up at the mine since the railways and power stations switched to oil. They continued to sell off equipment including an armoured car, a jeep and military type lorry and a rifle.

The managing director of Laidlaw Drew and Co. arrived in Malaya in April to test his oil burning equipment on Malayan railways locomotives.

May day was celebrated at Batu Arang with the opening of the new community hall and basketball courts, the laying of the foundation stone of the new union headquarters and the annual sports day. Mr. Warmington commented that just as the emergency was no longer a major factor, coal has lost its value and there was fear of unemployment. He hoped that it would be possible to show that the mine was still one of Malaya’s most valuable assets.

At the end of July the government decided to switch to using imported diesel oil for its locomotives and electricity stations and said it would be uneconomic to switch back and that they had no intention of subsidising a private company. The shares crept even lower to 50 cents on the news. Pre war they had been $3.40. Also in July one miner was killed in an underground explosion and two others were injured. A stray spark had ignited blasting dynamite prematurely.

It was decided to close down the second of three underground mines. 2,300 workers were sacked. There was only one underground pit and one open cast left working, employing 1,200 men. Less than half the number employed the previous year. John Drysdale considered the Government policy short sighted, especially given the Collieries co operation with it in the past. “The colliery has had a raw deal and the Government’s wrong,” he said. In August the Batu Arang Union held an emergency meeting, and more than 1,000 miners protested. The union had not been consulted. Business at the town was at a standstill, 16 shops had closed. 43 refuse and sanitation workers went on strike after their number was cut from seven to six in each gang and their hours and wages reduced. The Malayan trade union created a two-man team to look at unemployment at Batu Arang.

In August the papers reported “Mr. W. Gemmill, Chairman of J. A. Russell and Co., who have a big holding in Malayan Collieries, said in Kuala Lumpur yesterday that shareholders had been overlooked in the Batu Arang crisis. In the past six months the value of the company’s holdings had dropped from $1,750,000 to $300,000. Shareholders had spent $9,000,000 developing Batu Arang and had received only moderate dividends.” The collieries redeveloped another open cast mine and said that once it was in full production the last underground mine would close. Demand continued to drop.

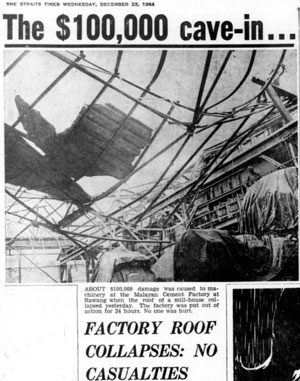

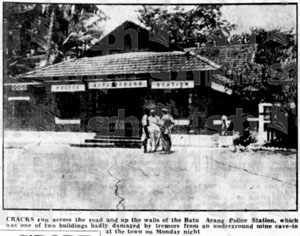

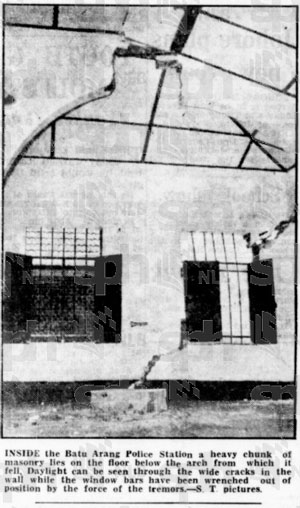

In September there was more bad luck when No. 3 mine, (disused), subsided at Batu Arang causing damage to the main office building and the police station. The town centre looked like an earthquake had struck it, with foot wide fissures in the roads. The A.G.M. in December revealed a loss $221,571. Revenue dropped by about $2.6 million as compared with the previous year.

1955

In February the Collieries' shares rose slightly due to reports that with the closure of two underground mines and cuts in overheads it might be possible for the company to make a small profit. It was known that they had a large holding in Malayan Cement, which was about to publish a very satisfactory balance sheet.

Another tremor hit Batu Arang on 11 February when the post office, co-operative store and eight shop houses were badly damaged. They had to be shored up with timber to prevent them from collapsing. The police station and barracks, damaged in the previous September, now had even wider and deeper cracks.

In May a shareholder’s circular reported that the mine was again in profit. The two underground mines had been closed and expenditure had been cut. in Ipoh, in May, at the A.G.M. of the F.M.S. chamber of mines, Douglas Waring, the chairman, said: “The Collieries at Batu Arang have supplied a large proportion of the needs of the Mining Industry, either directly or indirectly, for the past forty years, and have been a key industry engaged in making available one of Malaya’s natural resources; they have also provided considerable employment and amenities at Batu Arang, all, of which have been of benefit to the country. The general transition away from the use of coal as a means of supplying energy towards the use of oil or even other newer sources is probably inevitable and follows the pattern in other parts of the world; but in witnessing the trend of events, members of this Chamber must, I know, regret that the activities of the Collieries which has so closely been connected with the Tin Mining Industry are now on a reduced scale compared with the past.”

At their 37th A.G.M. the Collieries agreed a dividend of 10%. This was the first dividend for two years. They had made a profit for the year ended June 30 of $866,153 compared with a loss of $221,571 in the previous financial year. A further 570 jobs had been cut. They were considering reopening the brick and tile works because of the demand caused by increased building activities. They advertised burnt shale for surfacing roads. Redundant equipment was sold off.

Malayan Cement held its fifth A.G.M. in April. The production of cement was 20% higher than in 1954. Two thirds of the requirements of the Federation were being met.

1956

John Drysdale was awarded the CBE for public services in Selangor, “MR. JOHN DRYSDALE, becomes a Commander of the British Empire, (he) is chairman of the directors of Malayan Collieries Ltd. He has rendered outstanding service to the State of Selangor over a period of more than 20 years.”

In February the 167 strong workforce at Malayan Cement asked for an increase in wages, 14 days annual leave, a housing allowance and medical leave facilities. Following negotiations between the management and representatives of the National Union of Factory and General Workers, the management agreed to give a minimum daily wage of $4.02 to workers who would receive $2.76. Workers paid $6.12 a day would receive $6.69. The increases were backdated to March 1. The Company declared a dividend of 12-½% in April.

The Royal Exchange Assurance published an advertisement in February saying their chief agents were Messrs. J. A. Russell & Co. Ltd.

Greater use of road transport led to a number of fatal crashes being reported in the papers. Two workman died in an accident at Batu Arang when their truck overturned into an opencast. 500 workers attended their funeral in October. In November 1,000 Colliery workers led by Mr. P. K. R. Kurup, president of the Colliery Workers' Union asked the railways to use more coal so that they could keep their jobs. It followed a warning from the company that unless local industries used more coal the mine might have to close. The collieries continued to sell off redundant equipment. Their annual report recommended a dividend of 12-½%.

The F.M.S. chamber of mines reported on the Emergency. There had been a reduction in the number of incidents. Mines had had few attacks in the past year, but defences could not come down and staff had to stay alert. Few of the guerrillas were agreeing to an amnesty or laying down their weapons. They also discussed the training of Malayans for technical and managerial posts. Malayan candidates were being sent overseas to study because the qualifications needed were not available in Malaya. They were investigating setting up initial training at the Technical College in Kuala Lumpur and at the University.

1957 The Cement Works Expands

At the 7th A.G.M. of Malayan Cement John Drysdale announced that they were going to expand the works to double the production. Portland Cement would make the plant and machinery available. Demand exceeded supply. Regular monthly meeting were held with the union. The workforce had had their wages increased and the cost of materials was increasing. Portland Cement had loaned members of staff to train up local people for responsible positions, and one Malayan had been sent to the U.K. to train as works chemist. Another dividend of 12-½% was announced. They took out a half page advert in August announcing the commencing of the first stage of expansion and in November announced the issuing of shares to increase their capital.

The former plywood factory advertised as available for industrial redevelopment.

Straits Times 10 Dec. 1958 p.4.

1958

Collieries A restriction on tin production caused a 40% drop in coal production. In June the papers reported a proposal to reconstruct the railway line between Batu Arang and Batang Berjuntai. The Japanese took the line away during their occupation of Malaya. Tin and other minerals had been discovered in Kuala Selangor. “Two of the country's biggest mining companies are investing more than $36 million to develop the tin deposits discovered recently. Prospecting teams have also found other minerals such as gold and pencil lead in the area.” This article, does not name the Collieries as being one of the companies but is accompanied by a photograph of Batu Arang open cast.

All underground mining was stopped in July and only the open cast was used. The workforce was reduced by another 160 in September. The management announced a possible capital repayment to shareholders. It was put to an extraordinary general meeting in October and the decision was made to reduce the capital by 50%, from $4 million to $2. Production in September was 5,000 tons compared with 10,000 tons for 1957. There were 260 workers in September compared with 700 in September 1957. At the 40th A.G.M. in November John Drysdale said the only demand for coal was from the cement works and two tin dredges, but demand from the cement works would rise once the second kiln started. The labour force was now 210 and the population of Batu Arang 4,800. The company was encouraging the jobless to use its land for cultivation. They were investigating alternative uses for coal.

From 1 November the Collieries services were restricted to its 250 employees, there was free water for everybody but lighting had to be paid for. Street sweeping, garbage disposal and the services of the hospital were withdrawn. Batu Arang became neglected. The market place was covered in rubbish and stank and there were flies and mosquitoes. The Company wanted the Government to set up a town board to provide services. The president of the M.C.A. led a delegation to management but was referred to Government. They met with the district officer who referred them to the State Secretary. Batu Arang was private property and people would have to pay for essential services. The former plywood factory was advertised as available for industrial redevelopment.

1959 Cement.

Malayan Cement made a profit of $1,858,141. During the year the works produced 109,664 tons, the dividend was 12 ½% and shares were trading at $1.65. In March they announced that the new kiln had been installed and they would be producing 250.000 tons a year. Tiger cement would soon be available in all parts of the Federation. Phase one had cost $3 million had raised production to 21,000 tons a month. They planned phase two of its expansion costing another $2 million to increase production to 300,000 tons a year. Cheaper cement was being imported into the country that had affected sales.

In August the Sultan opened the Klang gates dam. It brought to an end the floods in K.L. and provided water for the town. It was built by the public works department. ” More than 1,600 tons of ice was used to chill the concrete mixture of millions of tons of Malayan Cement used in the building. This had been recommended by the designers. The ice was used to cool the concrete to ensure there was no shrinkage later, thus preventing cracks. It was entirely constructed by local artisans and special plant purchases.”

The Sultan also opened the extension of the cement works in September. The event was celebrated by the production of booklet and in a four-page supplement in the Straits Times. In September the papers reported: “Malayan Cement, the only factory of its kind in Malaya, has invested £7.5 million in the project which includes a second kiln, two grinding mills, extensions to existing buildings and ancillary equipment. The Rawang Factory has a rated capacity of over 200,000 tons of cement a year, although it can be worked up to produce 300,000 tons. The estimated annual consumption of cement in the Federation is about 250,000 tons and the company hopes to capture the entire market.”

1960 The end of Coal Mining at Batu Arang.

It was announced in January that the Collieries would stop production at the end of the month. The Company was intending to lease the land for rubber, but this would not provide any work for seven years. The Straits Times observed that it was a “tragic story” that within the space of six years a town that had a population of 12,000, with a workforce of 2,350 now had only 250 working. 50 million tons of coal was in the ground but it could not be sold. The town would survive only as a village. The Government agreed to the setting up of a local council and said it would grant permission for the changing of the title of some of its land from mining to agricultural.

The people of Batu Arang held a mass meeting to decide what to do. Mr. B.S. Pitchai, who was president of the Colliery Workers Union, and Mr. K. Kathir Velu, president of the Colliery Asian Staff Union, planned to ask the government for action and to ask the colliery for payments for sacked workers. They intended to stay at Batu Arang and had approached the company to buy their houses. Some had found new jobs in nearby mines or estates and some had been redeployed to the Cameron Highlands.

On the last day of January the last coal was loaded and the mine was shut down. 81 people were kept on the payroll to wind up affairs. Residents occupying the company’s houses were asked to leave. The people continued to press for a local council but were told by Government they had to set it up themselves. Medical facilities, light, water and cleaning supplied by the company would be extended for a short time but not indefinitely. By April Batu Arang was in “ a state of anarchy” with the collieries leaving and no local authority to take over. The collieries continued to sell off assets. Although they had stopped producing coal, the shale supplies to the cement works continued. The cement company would take over the shale winning operation and the equipment involved. The Colliery shares continued to be traded and rose to $1.80 in July with investors expecting a capital redistribution when the company went into liquidation. This was announced in mid July at which shares rose to $1.88.

Coal.

Noel Warmington the general manager of the collieries became ill at the end of 1958 and died in hospital in England in February. G. W. Warner replaced him.

Coal production was: July 6,775 tons: August 5,015 tons, and September 7,301 tons. Its 41st AGM declared a dividend of 12 ½% but John Drysdale announced the colliery would close in four months. Reserves of coal would last until February. The agreement to supply coal to the cement factory would expire in February and their conversion to oil was inevitable. Employment at the mine had been reduced to three Europeans- the general manager, an engineer, and an accountant- and a total Asian staff and workers of 260. There was speculation that the Company would go into liquidation and shares went up to $1.60.

The closure of the mine was one of the main subjects of discussion by the 75 unions attending the 9th AGM of the Malayan TUC. The unions passed a resolution asking for government to provide industrial development at Batu Arang, which had a population of about 2,000.